5. Newton’s Laws of Motion#

5.1. Forces#

The study of motion is called kinematics, which describes the way objects move through their velocity and acceleration.

The study of what causes objects to move is called dynamics, which describes the motion of objects and systems through forces. The foundation of dynamics are the laws of motion developed by Isaac Newton, although some of the fundamental principles were developed earlier by Galileo Galilei.

The development of Newton’s laws marked a transition from Renaissance thinking (i.e., reliance on ancient texts) to Scientific Revolution thinking which developed many of the fundamental pillars of the modern era. Newton’s description of mechanics is now described as classical mechanics where it applies to most situations until the 20th century. The development of modern physics was prompted by discoveries of subatomic particles which move at speeds comparable to the speed of light. To describe the motions of these particles, we need quantum mechanics.

5.1.1. Working Definition of Force#

We need a “working” definition of a force to help build some intuition until we get to the more formal definition given by Newton’s 2nd Law. An intuitive definition of a force is

a push or a pull.

A push or a pull has both magnitude (i.e., how hard) and a direction, so it is a vector quantity. Force can be represented by vectors or expressed as a multiple of a standard force.

Our everyday experience gives a good idea of how multiple forces add. If 2 people push in different directions on a third person (see Fig. 5.1), we might expect the total force to be in the direction of the resultant vector (or force). Forces, like vectors, are represented by arrows.

Fig. 5.1 Image Credit: Openstax#

Recall the spherical cow, where the solution was for an idealized and simplified situation. Physicists use free-body diagrams (or FBDs) to visualize and simplify our analysis of forces. A FBD is not a lifelike drawing, where it is only a sketch to organize your thinking.

A free-body diagram is not judged for beauty, symmetry, or originality. It is judged only on whether every force acting on the object is there.

The object or system is represented by

a single isolated point (or free body), and

only those forces acting on it (i.e., external forces) are shown.

Drawing Free-body Diagrams

Draw the object under consideration. This should be in 1980s style graphics as a point, circle, triangle, or rectangle. Place it at the origin of an \(xy\)-coordinate system.

Include all forces acting on the object and represent the forces as vectors. Do not include the net force or object’s force on the environment.

Resolve all force vectors into \(x\)- and \(y\)-components.

Draw a separate free-body diagram for each object in the problem.

Fig. 5.2 Image Credit: Openstax#

The strategy is illustrated in Fig. 5.2 with 2 examples. The video below gives a more in-depth general explanation.

5.1.2. Contact and Field Forces#

Let’s analyze force more deeply. Suppose a physics student sits at a table (see Fig. 5.3), working diligently on his homework :wink:.

Fig. 5.3 Image Credit: Openstax#

What external forces act on him? Can we determine the origin of these forces?

Forces are usually grouped into 2 categories: contact and field forces.

Contact forces are due to direct physical contact between objects. The student in Fig. 5.3 experiences contact forces \(\vec{C}\) (from the chair), \(\vec{F}\) (from the floor), and \(\vec{T}\) (from the table).

Field forces act without the necessity of physical contact between objects. They depend on the presence of a “field” near the body under consideration. Earth’s gravitational field causes the student to feel a gravitational force \(\vec{w}\), which is his weight.

As far as we know, there are only 4 fundamental force fields in nature. These are gravitational, electromagnetic, strong nuclear, and weak fields.

The gravitational field is responsible for the weight of a body.

The forces of electricity and magnetism are responsible for the attraction among atoms in bulk matter.

The strong nuclear and weak forces are effective over a short distance, no larger than an atomic nucleus.

Contact forces are fundamentally electromagnetic. Atomic charges interact electromagnetically with other atomic charges, which prevents objects from moving through one another (i.e., no clipping).

5.1.3. Vector Notation for Force#

The SI unit of force is called the Newton (abbreviated \(\rm N\)), which is the force needed to accelerate an object with a mass of \(1\ {\rm kg}\) at a rate of \(1\ {\rm m/s^2}\) (i.e., \(1\ {\rm N} = 1\ {\rm kg \cdot m/s^2}\)). Note that a small apple has a weight of about \(1\ \rm N\).

We can describe a force in the form

In Fig. 5.1, let’s suppose that ice skater 1 (on the left) pushes horizontally with a force of \(30\ {\rm N}\) to the right (or \(\vec{F}_1 = 30 \hat{i}\ {\rm N}\)). Similarly, if ice skater 2 (on the bottom) pushes with a force of \(40\ {\rm N}\) in the positive vertical direction, we would write \(\vec{F}_2 = 40\hat{j}\ {\rm N}\).

The resultant force causes the third ice skater to accelerate. The net external force \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\) is found by taking the vector sum of all external forces acting on an object or system. We can then represent the net external force (in general) as:

In this example, we have \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = \vec{F}_1 + \vec{F}_2 = 30\hat{i} + 40\hat{j}\ {\rm N}\). To find the magnitude of the net (resultant) force \(F_{\rm net}\), we sum the squares of the components and take the square root, or

where the direction is given by

measured from the positive \(x\)-axis, as shown in the free-body diagram in Fig. 5.1b.

Let’s suppose the ice skaters now push the third ice skater with \(\vec{F}_1 = 3\hat{i} + 8\hat{j}\ {\rm N}\) and \(\vec{F_2} = 5\hat{i} + 4\hat{j}\ {\rm N}.\)

What is the resultant of these two forces?

We recognize that force is a vector, and therefore, we must add using the rules for vector addition:

5.2. Newton’s 1st Law#

Newton’s 1st law is a restatement of Galileo’s principle of inertia, which states that an object in motion tends to slow down unless some effort is made to keep it moving. Newton’s 1st law gives a deeper explanation of this observation.

Newton’s 1st Law of Motion

A body at rest remains at rest or, if in motion, remains in motion at constant velocity unless acted on a by a net external force.

Note the expression “constant velocity”, which means that the object maintains a path along a straight line (since neither the magnitude nor direction changes). Also the verb “remains” tells us that it keeps on moving (or not moving) as part of the status quo.

Newton’s 1st law says that there must be a cause for any change in velocity (i.e., acceleration) to occur. The cause is a net external force. An object sliding across a table or floor slows down due to the net force of friction acting on the object. If friction disappears, will the object slow down?

Fig. 5.4 Image Credit: Openstax#

Consider an air hockey table (Fig. 5.4). When the air is turned off, the puck slides only a short distance before friction slows it to a stop. However, with the air turned on, it creates a nearly frictionless surface, and the puck glides a long distance without slowing down. If we know enough about the friction, we can accurately predict how quickly the object slows down.

Newton’s 1st law is general and can be applied to anything from an object sliding on table, a satellite in orbit, or even blood pumped from the heart. Experiments have verified that any change in velocity (speed or direction) must be caused by an external force.

Aristotle had claimed that objects had a natural state and needed little “angels” to keep the objects moving. It was Galileo who questioned this idea, which led him to ask the fundamental question: “What is the cause?” Thinking in terms of cause and effect is fundamentally different from the typical ancient Greek approach.

5.2.1. Gravitation and Inertia#

Regardless of the scale of an object, two properties remain valid: gravitation and inertia because they are both connected to mass.

Mass is a measure of the amount of matter in something. It has volume and takes up space.

Gravitation is the attraction of one mass to another. The magnitude of this attraction is your weight, and it is a force.

Mass is related to inertia, which is the ability of an object to resist changes in its motion, or to resist acceleration. Newton’s 1st law is often called the law of inertia.

5.2.2. Inertial Reference Frames#

Newton’s 1st law can also be stated as “Every body remains in its state of uniform motion in a straight line unless it is compelled to change that state by forces acting on it.”

To Newton, “uniform motion in a straight line” meant constant velocity, which includes the special case of zero velocity (or rest).

Therefore the 1st law says that the velocity of an object remains constant if the net force on it is zero, or

Newton’s 1st law is also considered as a statement about reference frames. It provides a method for identifying a special type of reference frame called the inertial reference frame.

In principle, we can make the net force on a body zero, if its velocity relative to a given reference frame is constant and then that frame is defined as inertial (recall Section 4.4.3). An inertial reference frame is one where Newton’s 1st law is valid.

Inertial Reference Frame

A reference frame moving at constant velocity relative to an inertial reference frame is also inertial. A reference frame accelerating relative to an inertial frame is not inertial.

Are inertial frames common in nature?

A reference frame at rest to the most distant (or “fixed”) stars is inertial. All frames moving uniformly with respect to this fixed-star frame are also inertial. For example, a nonrotating reference frame attached to the Sun is (for all practical purposes) inertial because its velocity relative to the fixed stars does not vary by more than one part in \(10^{10}\).

Earth accelerates relative to the fixed stars because it rotates on its axis and revolves around the Sun. Hence a reference frame attached to its surface is not inertial. For most problems, such a frame serves as a sufficiently accurate approximation to an inertial frame because the acceleration relative to the fixed stars is small (\({\sim}10^{-2}\ {\rm m/s^2}\)). Thus we consider reference frames fixed to the Earth as inertial.

No particular inertial frame is more special than any other. All inertial frames are equivalent. In analyzing a problem, we choose one particular inertial frame simply based on convenience.

5.2.3. Newton’s 1st Law and Equilibrium#

Newton’s first law tells us about the equilibrium of a system (i.e., \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = 0\)). From Fig. 5.1, the forces combine to form a net external force: \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = \vec{F}_1 + \vec{F}_2\). To create equilibrium, we require a balancing force that will produce a net force of zero.

This force must be equal in magnitude, but opposite in direction to \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\) (i.e., \(\vec{F}_{\rm bal} = -\vec{F}_{\rm net}\)).

For the ice skaters, we found \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = 30\hat{i} + 40\hat{j}\, {\rm N}\), where the balancing force is

Newton’s 1st law in vector form is given as

For the net force to equal zero, the velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}\) of the object is a constant.

Derivative of a Constant (Calculus-framing)

From calculus, we have the constant rule which means that for any function \(f(x) = c\) (where \(c\) is a constant), the derivative \(f^\prime(x) = 0\).

What does this mean for an object moving with constant velocity? We have loosely defined a force as a push or pull (or causing an object to accelerate). Recall the definition of acceleration as

which means the acceleration is the slope of the velocity curve. If \(\vec{\rm v}(t) = c\), then the slope is equal to zero.

If there is no acceleration, then there is no force (assuming mass remains constant).

If a car is at rest, the only forces acting on the car are: weight and the contact force pushing up on the car (see Fig. 5.5). A nonzero net force is required to change the state of motion of the car. As a car moves with constant velocity, the friction force propels the car forward and opposes the drag force against it.

Fig. 5.5 Image Credit: Openstax#

Interactive Simulation: Forces and Motion

5.2.3.1. Example Problem: Applying Newton’s 1st Law to your car#

Exercise 5.1

The Problem

Newton’s laws can be applied to all physical processes involving force and motion, including something as mundane as driving a car.

(a) Your car is parked outside your house. Does Newton’s first law apply in this situation? Why or why not?

(b) Your car moves at constant velocity down the street. Does Newton’s first law apply in this situation? Why or why not?

The Model

In both situations, the car is modeled as a single object moving in an inertial reference frame fixed to the ground. Newton’s first law applies when the vector sum of the external forces acting on the object is zero, which implies zero acceleration.

In part (a), the car is at rest on level ground. Forces act on the car, but the car does not accelerate.

In part (b), the car moves at constant velocity on level ground. Forces act on the car, but its velocity does not change in either magnitude or direction.

In both cases, the question is whether the forces acting on the car balance so that the net force is zero.

The Math

Newton’s first law states that if the net external force on an object is zero, then the object does not accelerate. This can be written as

An object with zero acceleration is either at rest or moving with constant velocity.

(a) Parked car

Choose a coordinate system with \(+\hat{j}\) pointing upward. Two forces act on the car:

The weight of the car, which acts downward and is written as \(\overrightarrow{W} = -w\, \hat{j}\)

The force exerted by the ground on the car, which acts upward and is written as \(\vec{N} = n\, \hat{j}\)

The net force on the car is the vector sum of these forces,

Since the car is at rest and does not accelerate, Newton’s first law requires that the net force be zero. This implies

so the upward force exerted by the ground balances the downward weight of the car.

(b) Car moving at constant velocity

Choose a coordinate system with \(+\hat{i}\) in the direction of motion and \(+\hat{j}\) upward. Forces act on the car both vertically and horizontally.

Vertically, the downward weight \(\overrightarrow{W} = -w\, \hat{j}\) and the upward force from the ground \(\vec{N} = n\, \hat{j}\) must balance because the car does not accelerate vertically:

Horizontally, a forward force from the road on the tires acts in the \(+\hat{i}\) direction and is written as

A resistive force due to air drag and rolling resistance acts opposite the motion and is written as

Constant velocity implies zero acceleration, so the net horizontal force must be zero:

With both the vertical and horizontal forces balanced, the total net force on the car is zero.

The Conclusion

(a) Yes. Newton’s first law applies to a parked car because the forces acting on it balance so that the net force is zero. With zero net force, the acceleration is zero and the car remains at rest.

(b) Yes. Newton’s first law also applies to a car moving at constant velocity. Although forces act on the car, they balance in both the vertical and horizontal directions, producing zero net force. With zero net force, the car does not accelerate and continues moving with constant velocity.

The Verification

We verify the qualitative force balance by assigning representative vector magnitudes and directions, summing the force vectors, and showing that the net force is zero in both scenarios. The resulting vector diagrams serve as free-body diagrams for each case.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

w = 1.0

n = 1.0

f = 0.6

W_a = np.array([0.0, -w])

N_a = np.array([0.0, +n])

Fnet_a = W_a + N_a

W_b = np.array([0.0, -w])

N_b = np.array([0.0, +n])

F_road = np.array([+f, 0.0])

F_res = np.array([-f, 0.0])

Fnet_b = W_b + N_b + F_road + F_res

print("Scenario (a) net force:", Fnet_a)

print("Scenario (b) net force:", Fnet_b)

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = F[0], F[1]

ax.annotate("", xy=(Fx, Fy), xytext=(0.0, 0.0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

# Label placement logic

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy): # horizontal force

xlab = Fx + 0.2*np.sign(Fx)

ylab = Fy

ha, va = "center", "center"

else: # vertical force

xlab = Fx

ylab = Fy + 0.15*np.sign(Fy)

ha, va = "center", "center"

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment=ha,verticalalignment=va)

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-2, 2)

ax.set_ylim(-2, 2)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7, 3.8), dpi=120)

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(121)

draw_fbd(ax1, [N_a, W_a],[r"$\vec{N}$", r"$\overrightarrow{W}$"],r"Parked car: $\sum \vec{F}=\vec{0}$")

ax1.text(0.,-1.5,r"$v = 0\ {\rm km/h}$ ",fontsize=11, horizontalalignment='center',verticalalignment='center')

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(122)

draw_fbd(ax2, [N_b, W_b, F_road, F_res],[r"$\vec{N}$", r"$\overrightarrow{W}$",

r"$\vec{F}_{\rm{road}}$", r"$\vec{F}_{\rm{res}}$"],r"Constant velocity: $\sum \vec{F}=\vec{0}$")

ax2.text(-0.5,-1.5,r"$v = 50\ {\rm km/h}$ ",fontsize=11, horizontalalignment='center',verticalalignment='center')

ax2.annotate("", xy=(1, -1.5), xytext=(0.25, -1.5),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Scenario (a) net force: [0. 0.]

Scenario (b) net force: [0. 0.]

5.3. Newton’s 2nd Law#

Newton’s 2nd law gives the cause-and-effect relationship between force and changes in motion. It is quantitative and used extensively to calculate what happens in situations involving a force.

5.3.1. Force and Acceleration#

What do we mean by a change in motion?

A change in motion is equivalent to a change in velocity (i.e., an acceleration). Newton’s 1st law says that a net external force causes a change in motion, and thus, we see that a net external force causes nonzero acceleration.

An external force is one that is outside the system of interest. In Fig. 5.6a, the system of interest is the car plus the person within it. The two forces exerted by the students outside are external forces.

An internal force acts between elements of the system. Thus the force the person exerts holding onto the steering wheel is an internal force.

Fig. 5.6 Image Credit: Openstax#

Only external forces affect the motion of a system, according to Newton’s 1st law. Therefore, we must define the boundaries of the system to separate the internal from external forces.

In Fig. 5.6a, there are arrows denoting the external forces present:

The weight \(\vec{w}\) includes the car + person inside.

The car is supported by the ground \(\vec{N}\), which will cancel the weight, since the car is not floating nor sinking.

The friction \(f\) resists the motion and must be oriented opposite (to the left).

The forces from each student pushing (\(\vec{F}_1\) and \(\vec{F}_2\)) are applied to accelerate the car to the right.

All the forces add together to produce the net force \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\) (see Fig. 5.6b). The free-body diagram (Fig. 5.6a) shows all of the forces acting on the system, where the dot at the center represents the center-of-mass. Forces in the same direction are shown collinearly.

In Fig. 5.6c, a larger net external force produces a larger acceleration \(\left(\vec{a}^\prime > \vec{a}\right)\) when the tow truck pulls the car. The acceleration is proportional to and in the same direction as the net external force acting on a system. Mathematically this is written as

where the symbol \(\propto\) (or \propto) means “proportional to.”

Once the system of interest is chosen, identify the external force and ignore the internal ones. It is a huge simplification to disregard the numerous internal forces acting between objects within the system. This simplification helps us solve some complex problems.

Recall that inertia is the “resistance to motion” and is related to an objects mass. Therefore it seems reasonable that a more massive object requires more acceleration for it to move.

In Fig. 5.7, the same net external force applied to a basketball produces a much smaller acceleration when it is applied to an SUV.

Fig. 5.7 Image Credit: Openstax#

Therefore, we can write the proportional relationship between acceleration and mass as

where \(m\) is the mass of the system and \(a\) is the magnitude of the acceleration. Combining the two proportionalities yields Newton’s 2nd law.

Newton’s 2nd Law of Motion

The acceleration of a system is

directly proportional to the external force acting on the system,

in the same direction as the external force acting on the system, and

inversely proportional to its mass.

In equation form, Newton’s 2nd law is

Since the mass \(m\) is a scalar, we can see that it scales the vector \(\vec{a}\) to give the net external force \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\). Also we can use the properties of vectors to write the scalar equivalent as

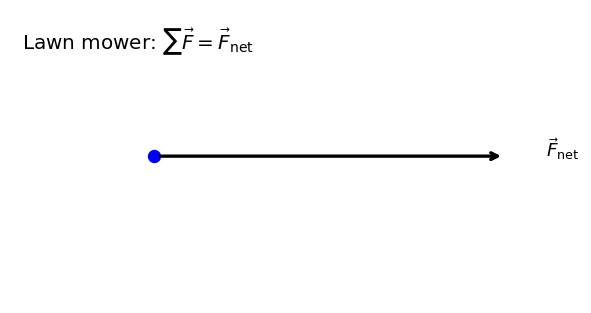

5.3.1.1. Example Problem: Pushing a Lawnmower#

Exercise 5.2

The Problem

Suppose that the net external force (push minus friction) exerted on a lawn mower is \(51\ \text{N}\) (about \(11\ \text{lb}.)\) parallel to the ground (Figure 5.8). The mass of the mower is \(24\ \text{kg}\). What is its acceleration?

Fig. 5.8 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

Model the lawn mower as a particle moving on level ground. The problem states the net external force is already known and is horizontal, so we do not need to model the individual forces from the push and friction separately. Because the net force is parallel to the ground, the acceleration is also horizontal. We take the mower’s mass to be constant and treat the motion as one-dimensional along the ground.

Note

Figure 5.8 shows only the net force for simplicity. Several forces act on the lawn mower.

The weight \(\vec{w}\) pulls down on the mower, toward the center of the Earth, where this produces a contact force on the ground. The ground must exert an upward force on the lawn mower, known as the normal force \(\vec{N}\). These forces are balanced and do not produce a vertical acceleration. You should include these forces in your free-body diagrams to make sure you haven’t left out any forces.

The Math

Newton’s second law relates the net force on an object to its acceleration. In vector form,

Choose \(+\hat{i}\) to the right, parallel to the ground. The net force is given as a single horizontal vector,

Since the motion is along \(\hat{i}\), write the acceleration as \(\vec{a} = a\,\hat{i}\). Substitute into Newton’s second law:

The unit vectors are the same on both sides, so the magnitudes must satisfy

Solve for \(a\):

Using \(1\ \text{N} = 1\ \text{kg}\cdot \text{m/s}^2\), the units reduce to \(\text{m/s}^2\):

The Conclusion

The lawn mower’s acceleration is \(2.1\ \text{m/s}^2\) in the same direction as the net force, which is parallel to the ground.

The Verification

We verify the result by recomputing \(a = F_{\text{net}}/m\) numerically and by showing that \(ma\) reproduces the given net force.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

Fnet = 51.0 # N

m = 24.0 # kg

a = Fnet/m

Fcheck = m*a

print("Computed acceleration a =", a, "m/s^2")

print("Check: m*a =", Fcheck, "N")

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = F[0], F[1]

ax.annotate("", xy=(Fx, Fy), xytext=(0.0, 0.0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy):

xlab = Fx + 0.2*np.sign(Fx)

ylab = Fy

else:

xlab = Fx

ylab = Fy + 0.25*np.sign(Fy)

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment='center')

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-0.5,1.2)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5,0.5)

# Free-body diagram for this problem shows only the net force vector.

Fnet_vec = np.array([1.2, 0.0]) # scaled for plotting

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5, 4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, [Fnet_vec], [r"$\vec{F}_{\rm{net}}$"], r"Lawn mower: $\sum \vec{F}=\vec{F}_{\rm{net}}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Computed acceleration a = 2.125 m/s^2

Check: m*a = 51.0 N

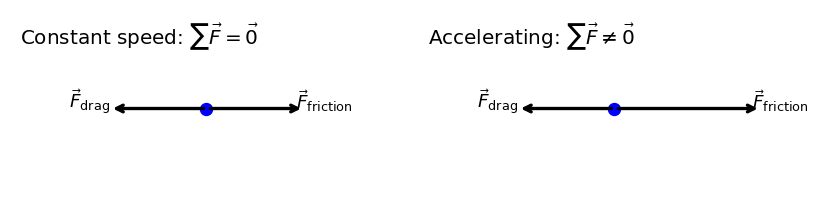

5.3.1.2. Example Problem: Comparing Forces#

Exercise 5.3

The Problem

(a) The car shown in Figure 5.9 is moving at a constant speed. Which force is bigger, \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) or \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\)? Explain.

(b) The same car is now accelerating to the right. Which force is bigger, \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) or \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\)? Explain.

Fig. 5.9 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

Model the car as a single object moving along a horizontal road. Only horizontal forces are relevant to the motion described. The force \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) represents the forward force exerted by the road on the tires, while \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\) represents resistive forces such as air drag that oppose the motion.

In part (a), the car moves at constant speed, so its acceleration is zero. In part (b), the car accelerates to the right, so its acceleration is nonzero and directed to the right.

The analysis depends on whether the net horizontal force is zero or nonzero.

The Math

Newton’s first law states that if the net external force on an object is zero, then the object moves with constant velocity. Newton’s second law states that a nonzero net external force produces acceleration. In vector form,

and

Choose \(+\hat{i}\) to the right. The horizontal forces on the car are \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) in the \(+\hat{i}\) direction and \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\) in the \(-\hat{i}\) direction.

(a) Constant speed

Because the car moves at constant speed, its acceleration is zero. Newton’s first law applies, so the net horizontal force must be zero:

This requires that the magnitudes of the two forces be equal and their directions opposite.

(b) Accelerating to the right

Because the car accelerates to the right, the net horizontal force must be directed to the right. Newton’s second law applies:

For the net force to point in the \(+\hat{i}\) direction, the forward friction force must have a greater magnitude than the backward drag force.

The Conclusion

(a) When the car moves at constant speed, the net horizontal force is zero. Therefore, \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) and \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\) have equal magnitudes and opposite directions.

(b) When the car accelerates to the right, the net horizontal force points to the right. Therefore, the magnitude of \(\vec{F}_{\text{friction}}\) is greater than the magnitude of \(\vec{F}_{\text{drag}}\).

The Verification

We verify the force relationships qualitatively by constructing simple free-body diagrams for each case and checking whether the horizontal forces balance or produce a net force to the right.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Representative magnitudes (arbitrary units)

f_drag = 1.0

f_fric_equal = 1.0

f_fric_larger = 1.5

F_drag = np.array([-f_drag, 0.0])

F_fric_equal = np.array([f_fric_equal, 0.0])

F_fric_larger = np.array([f_fric_larger, 0.0])

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

ax.annotate("", xy=(F[0], F[1]), xytext=(0.0, 0.0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(F[0]) > abs(F[1]):

xlab = F[0] + 0.2*np.sign(F[0])

ylab = F[1]

else:

xlab = F[0]

ylab = F[1] + 0.25*np.sign(F[1])

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment='center')

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([]); ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-2, 2)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 1)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7, 3.8), dpi=120)

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(121)

draw_fbd(ax1,

[F_fric_equal, F_drag],

[r"$\vec{F}_{\rm friction}$", r"$\vec{F}_{\rm drag}$"],

r"Constant speed: $\sum \vec{F}=\vec{0}$")

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(122)

draw_fbd(ax2,

[F_fric_larger, F_drag],

[r"$\vec{F}_{\rm friction}$", r"$\vec{F}_{\rm drag}$"],

r"Accelerating: $\sum \vec{F}\neq\vec{0}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

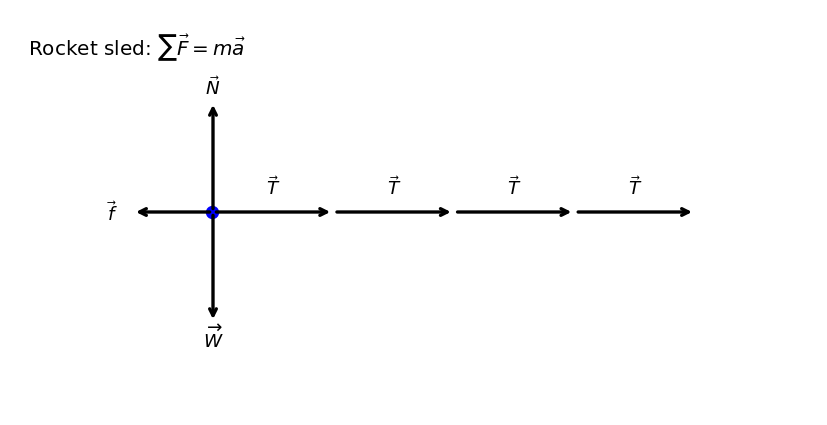

5.3.1.3. Example Problem: Thrust on a Sled#

Exercise 5.4

The Problem

Before space flights carrying astronauts, rocket sleds were used to test aircraft, missile equipment, and physiological effects on human subjects at high speeds. They consisted of a platform that was mounted on one or two rails and propelled by several rockets.

Calculate the magnitude of force exerted by each rocket, called its thrust \(T\), for the four-rocket propulsion system shown in Figure 5.10. The sled’s initial acceleration is \(49\ \text{m/s}^2\), the mass of the system is \(2100\ \text{kg}\), and the force of friction opposing the motion is \(650\ \text{N}\).

Fig. 5.10 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

The system of interest is the rocket sled together with its rockets and rider. External forces act on this system. Vertically, the normal force from the rails and the weight of the system act, but there is no vertical acceleration, so the vertical forces cancel.

Horizontally, four identical rockets each exert a thrust of magnitude \(T\) in the forward direction, while friction exerts a force of magnitude \(f\) opposing the motion. The sled accelerates horizontally, so the net horizontal force is nonzero and directed forward.

The motion is treated as one-dimensional along the horizontal direction.

The Math

Newton’s second law relates the net external force on a system to its acceleration,

Choose \(+\hat{i}\) to the right, in the direction of motion. The horizontal forces on the sled are four thrust forces, each of magnitude \(T\), acting in the \(+\hat{i}\) direction, and a friction force of magnitude \(f\) acting in the \(-\hat{i}\) direction. The net horizontal force is therefore

The acceleration is horizontal and can be written as \(\vec{a} = a\,\hat{i}\). Substituting into Newton’s second law gives

Because the unit vectors are the same on both sides, the magnitudes must satisfy

Solving for the total thrust \(4T\) yields

Substitute the given values:

Evaluating this expression gives

The thrust from each individual rocket is one quarter of the total thrust,

The Conclusion

Each rocket must provide a thrust of approximately \(2.5 \times 10^{4}\ \text{N}\) in order for the four-rocket sled system to accelerate at \(49\ \text{m/s}^2\) while overcoming the opposing friction force.

The magnitude of the thrust is extremely large compared to everyday forces, reflecting the extreme accelerations involved in rocket-sled experiments. An acceleration of \(49\ \text{m/s}^2\) corresponds to about \(5g\), where \(g\) is the acceleration due to gravity. Historical rocket-sled tests reached even larger accelerations, on the order of tens of \(g\), to study human tolerance to rapid acceleration and deceleration.

This example illustrates several key ideas of Newton’s second law. First, forces acting in the same direction add, while opposing forces subtract. Second, choosing the correct system is essential: the thrust forces are external to the sled-rocket-rider system, while internal forces between components of the system do not appear. Finally, Newton’s second law provides a direct and quantitative link between force, mass, and acceleration, allowing us to predict the performance of real physical systems.

The Verification

We verify the result numerically by recomputing the total thrust required from Newton’s second law and then dividing by four to obtain the thrust of each rocket.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values (2 significant figures)

m = 2100.0 # kg

a = 49.0 # m/s^2

f = 650.0 # N

# Calculations

total_thrust = m*a + f

T = total_thrust/4

# Sig-fig–appropriate output

print(f"Total thrust 4T = {total_thrust:.2g} N")

print(f"Thrust per rocket T = {T:.2g} N")

# --- Free-body diagram ---

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note, chain_label=r"$\vec{T}$"):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

x0, y0 = 0.0, 0.0

x_chain, y_chain = 0.0, 0.0

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = float(F[0]), float(F[1])

# Thrusts: draw tip-to-tail (OpenStax style)

if lab == chain_label:

ax.annotate("", xy=(x_chain + Fx, y_chain + Fy), xytext=(x_chain, y_chain),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

ax.text(x_chain + 0.5*Fx, y_chain + 0.5*Fy + 0.18, lab, fontsize=11,

horizontalalignment="center")

x_chain += Fx

y_chain += Fy

continue

# All other forces: draw from the origin dot

ax.annotate("", xy=(x0 + Fx, y0 + Fy), xytext=(x0, y0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

# Your label logic (horizontal vs vertical)

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy):

xlab = x0 + Fx + 0.2*np.sign(Fx)

ylab = y0 + Fy

else:

xlab = x0 + Fx

ylab = y0 + Fy + 0.15*np.sign(Fy)

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment="center",verticalalignment="center")

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values(): spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-2, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-2, 2)

# --- Example usage for the rocket sled FBD ---

T_plot = 1.2

f_plot = 0.8

n_plot = 1.1

w_plot = 1.1

forces = [np.array([-f_plot, 0.0]), np.array([0.0, n_plot]), np.array([0.0, -w_plot]),

np.array([T_plot, 0.0]), np.array([T_plot, 0.0]), np.array([T_plot, 0.0]), np.array([T_plot, 0.0])]

labels = [r"$\vec{f}$", r"$\vec{N}$", r"$\overrightarrow{W}$",

r"$\vec{T}$", r"$\vec{T}$", r"$\vec{T}$", r"$\vec{T}$"]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7, 3.8), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, r"Rocket sled: $\sum \vec{F}=m\vec{a}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Total thrust 4T = 1e+05 N

Thrust per rocket T = 2.6e+04 N

5.3.2. Component Form of Newton’s 2nd Law#

Newton’s 2nd law can be written in vector form as

Writing this equation in component form gives

Once we write Newton’s 2nd law in component form, the quantities \(F_x\), \(F_y\), \(F_z\), \(a_x\), \(a_y\), and \(a_z\) are scalars, so vector notation is no longer used. Each component equation relates forces and acceleration along a single axis and can be analyzed independently.

The second law is a description of how a body responds mechanically to its environment. The influence of the environment is the net force \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\), the body’s response is the acceleration \(\vec{a}\), and the strength of the response is inversely proportional to the mass \(m\). The larger the mass of an object, the smaller its acceleration to a given net force.

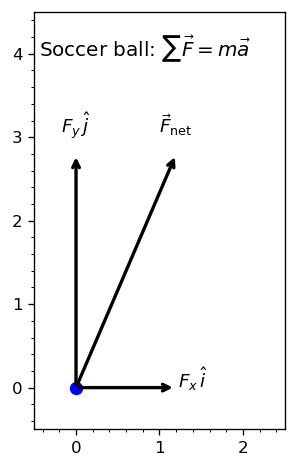

5.3.2.1. Example Problem: Force on a Soccer Ball#

Exercise 5.5

The Problem

A \(0.400\ \text{kg}\) soccer ball is kicked across the field by a player; it undergoes acceleration given by \(\vec{a} = 3.00\hat{i} + 7.00\hat{j}\ \text{m/s}^2.\) Find (a) the resultant force acting on the ball and (b) the magnitude and direction of the resultant force.

The Model

Model the ball as a particle. The given acceleration is already written in \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) form, so we apply Newton’s second law directly in vector form. The net force on the ball is related to the acceleration by

The Math

Because the acceleration vector is already expressed in terms of its \(x\)- and \(y\)-components, we can multiply each component by the mass to obtain the corresponding components of the net force.

Substituting the given values for the mass and acceleration,

Distributing the mass across the components gives

This expression answers part (a): the net force acting on the ball is a vector with both horizontal and vertical components.

To answer part (b), we determine the magnitude and direction of this force. The magnitude of a vector written in component form is found using the Pythagorean theorem:

Substituting the force components,

The direction of the force is measured relative to the \(+\hat{i}\) axis. Using the definition of the tangent function,

The Conclusion

The resultant (net) force is \( \vec{F}_{\rm net} = 1.20\hat{i} + 2.80\hat{j}\ \text{N},\) where the magnitude and direction are \(F_{\rm net} = 3.05\ \text{N},\ \text{and } \theta = 66.8^\circ.\)

Newton’s second law is a vector equation: the acceleration components determine the force components direction-by-direction. Writing \(\vec{F}_{\rm net}\) in \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) form tells us how the force is split between the horizontal and vertical directions, while the magnitude and angle describe the same force in an overall “how big and which way” form. Both descriptions represent the same physical net force.

The Verification

We verify the force components using \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = m\vec{a}\), compute the magnitude and angle, and draw a free-body diagram showing the net force vector and its \(x\)- and \(y\)-components.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

m = 0.400

ax_val = 3.00

ay_val = 7.00

Fx = m*ax_val

Fy = m*ay_val

Fmag = np.sqrt(Fx**2 + Fy**2)

theta = np.degrees(np.arctan2(Fy, Fx))

print(f"F_net,x = {Fx:.2f} N")

print(f"F_net,y = {Fy:.2f} N")

print(f"|F_net| = {Fmag:.2f} N")

print(f"theta = {theta:.1f} deg")

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note):

ax.plot(0.0, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

ax.annotate("", xy=(F[0], F[1]), xytext=(0.0, 0.0),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(F[0]) > abs(F[1]):

xlab = F[0] + 0.2*np.sign(F[0])

ylab = F[1]

else:

xlab = F[0]

ylab = F[1] + 0.25*np.sign(F[1])

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment="center")

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

#ax.set_xticks([]); ax.set_yticks([])

#or spine in ax.spines.values():

# spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-0.5, 2.5);

ax.set_ylim(-0.5, 4.5)

ax.minorticks_on()

# Force vectors for plotting (scaled to fit nicely on the axes)

scale = 1.0

Fnet_vec = np.array([scale*Fx, scale*Fy])

Fx_vec = np.array([scale*Fx, 0.0])

Fy_vec = np.array([0.0, scale*Fy])

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5, 4), dpi=120)

axp = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(axp,

[Fnet_vec, Fx_vec, Fy_vec],

[r"$\vec{F}_{\rm net}$", r"$F_x\,\hat{i}$", r"$F_y\,\hat{j}$"],

r"Soccer ball: $\sum \vec{F}=m\vec{a}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

F_net,x = 1.20 N

F_net,y = 2.80 N

|F_net| = 3.05 N

theta = 66.8 deg

5.3.2.2. Example Problem: Mass of a Car#

Exercise 5.6

The Problem

Find the mass of a car if a net force of \(-600.0\,\hat{j}\ \text{N}\) produces an acceleration of \(-0.2\,\hat{j}\ \text{m/s}^2\).

The Model

The car is modeled as a particle subject to a net external force. The force and the resulting acceleration are both given as vectors directed along the \(\hat{j}\) axis, indicating one-dimensional motion along that axis. The mass of the car is assumed to be constant and is treated as a scalar property of the system. No additional forces or interactions are considered beyond the stated net force.

The Math

Newton’s second law relates the net external force acting on an object to its acceleration through the object’s mass. In vector form, this relationship is written as

Because mass \(m\) is a scalar quantity, vector division is not defined. However, when the net force and acceleration point in the same direction, their magnitudes can be related using the scalar form of Newton’s second law. Taking magnitudes of both sides gives

The given force and acceleration vectors both point in the \(-\hat{j}\) direction, so only their magnitudes are required. The magnitude of the net force is \(F_{\rm net} = 600.0\ \text{N}\), and the magnitude of the acceleration is \(a = 0.2\ \text{m/s}^2\).

Substituting these values yields

Using the definition \(1\ \text{N} = 1\ \text{kg}\cdot\text{m/s}^2\), the units reduce correctly to kilograms, giving

The Conclusion

The mass of the car is \(3000\ \text{kg}\). This result represents an intrinsic property of the car and does not depend on the direction of the applied force or the acceleration, only on their magnitudes.

The Verification

We verify the result numerically by computing the ratio of the force magnitude to the acceleration magnitude using the scalar form of Newton’s second law.

import numpy as np

Fnet = 600.0 # N

a = 0.2 # m/s^2

m = Fnet / a

print(f"Computed mass m = {m:.0f} kg")

5.3.2.3. Example Problem: Several Forces#

Exercise 5.7

The Problem

A particle of mass \(m = 4.0\ \text{kg}\) is acted upon by four forces of magnitudes \(F_1 = 10.0\ \text{N}\), \(F_2 = 40.0\ \text{N}\), \(F_3 = 5.0\ \text{N}\), and \(F_4 = 2.0\ \text{N}\), with the directions as shown in the free-body diagram in Fig. 5.11. What is the acceleration of the particle?

Fig. 5.11 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

The system consists of a single particle moving in the \(x\)–\(y\) plane under the action of four external forces. The particle is treated as a point mass.

A Cartesian coordinate system is chosen with the positive \(x\)-axis pointing to the right and the positive \(y\)-axis pointing upward. Each force is assumed to act in a fixed direction as shown in the free-body diagram. No constraints restrict the motion, so the particle may accelerate in both the \(x\)- and \(y\)-directions.

The Math

Newton’s second law relates the net external force acting on the particle to its acceleration. Because the motion is two-dimensional, the vector equation is written in component form and applied independently along each axis:

In the \(x\)-direction, the force \(F_1\) contributes a component \(F_1 \cos 30^\circ\) in the positive \(x\)-direction, while \(F_3\) acts entirely in the negative \(x\)-direction. Thus,

Substituting numerical values gives

In the \(y\)-direction, the upward forces are the vertical component of \(F_1\) and the force \(F_4\), while \(F_2\) acts downward. The force balance becomes

Substituting values,

Combining the components, the acceleration vector is

The Conclusion

The particle accelerates with components \(a_x = 0.92\ \text{m/s}^2\) and \(a_y = -8.3\ \text{m/s}^2\). This means the motion is predominantly downward, with a much smaller acceleration to the right.

The result reflects the fact that the large downward force \(F_2\) dominates the vertical force balance, while the horizontal forces partially cancel. The direction and magnitude of the acceleration are entirely determined by the vector sum of the applied forces and the particle’s mass.

The Verification

The force components are recomputed numerically and divided by the mass to confirm the acceleration components obtained analytically.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# -----------------------------

# Given values

# -----------------------------

m = 4.0

F1 = 10.0

F2 = 40.0

F3 = 5.0

F4 = 2.0

theta = np.deg2rad(30.0)

# -----------------------------

# Force components

# -----------------------------

F1_vec = np.array([F1*np.cos(theta), F1*np.sin(theta)])

F2_vec = np.array([0.0, -F2])

F3_vec = np.array([-F3, 0.0])

F4_vec = np.array([0.0, F4])

# Net force and acceleration

F_net = F1_vec + F2_vec + F3_vec + F4_vec

a_vec = F_net / m

# Sig-fig–appropriate output (2 sig figs)

print(f"Net force vector (N): [{F_net[0]:.2g}, {F_net[1]:.2g}]")

print(f"Acceleration vector (m/s^2): [{a_vec[0]:.2g}, {a_vec[1]:.3g}]")

Net force vector (N): [3.7, -33]

Acceleration vector (m/s^2): [0.92, -8.25]

5.3.3. Newton’s 2nd Law and Momentum#

Newton actually stated his 2nd law in terms of momentum

“The instantaneous rate at which a body’s momentum changes is equal to the net force acting on the body.”

This is written by the vector equation:

Momentum was described by Newton as “quantity of motion,” or a way of combining both the velocity and mass of an object. For now, it’s sufficient to define momentum \(\vec{p}\) as the product of the mass of the object \(m\) and its velocity \(\vec{\rm v}\):

Since velocity is a vector, so is momentum. If we substitute our definition of momentum into Newton’s 2nd law, we find

Thus, we see that the momentum form of Newton’s 2nd law reduces to the form given earlier.

5.4. Mass and Weight#

Mass and weight are often used interchangeably in everyday conversation. In physics, however, there is an important distinction. Weight is the pull of gravitational pull on an object, where it depends on the distance to the center of an object.

Unlike weight, mass does not vary with distance. The mass of an object is the same on Earth’s surface, in orbit, or on the surface of the Moon.

5.4.1. Units of Force#

The scalar equation \(F_{\rm net} = ma\) is used to define the net force in terms of mass, length, and time. The SI unit of force is the newton. Using \(F_{\rm net} = ma\), we can see that

You’re probably more familiar with another unit of force, which is the pound \((\rm lb)\), where \(1\ {\rm lb} = 4.448\ {\rm N}\). An even more historical measurement of weight is the stone, where \(1\ {\rm st} = 14\ {\rm lb} \approx 62.3\ {\rm N}\).

Use the Python code below to convert your weight into newtons or stones.

import numpy as np

lb_to_N = 4.448 # Newtons in a pound

st_to_N = 14*lb_to_N #Newtons in a stone

my_weight = 150 #lbs

weight_N = my_weight*lb_to_N

weight_st = weight_N/st_to_N

print(f"My weight is {weight_N:.0f} N or about {weight_st:.2g} stone.")

My weight is 667 N or about 11 stone.

5.4.2. Weight and Gravitational Force#

When an object is dropped on Earth, it accelerates toward Earth’s center. Newton’s 2nd law says that a net force on an object is responsible for its acceleration. If air resistance is negligible, the net force on a falling object is the gravitational force, which is called its weight \(\vec{w}\), or its force due to gravity acting on an object of mass \(m\).

Weight is denoted as a vector because it has a direction (down) and hence, weight is a downward force. The magnitude of weight is denoted by \(w\). Using Newton’s 2nd law, we can derive an equation for weight.

Consider an object with mass \(m\) falling toward Earth. It experiences only the downward force of gravity, which is the weight \(\vec{w}\). Newton’s 2nd law says that the magnitude of the net external force on an object is \(\vec{F}_{\rm net} = m\vec{a}\). We know that the acceleration due to gravity is \(\vec{g}\), or \(\vec{a} = \vec{g}\).

Weight

The gravitational force on a mass is its weight. We can write this in vector form,

where \(m\) is the mass and \(\vec{w}\) is the weight. In scalar form, we can write

The weight of a \(1\)-kg object on Earth is \(9.81\ {\rm N}\):

When the net external force on an object is its weight, we say that it is in free fall, which means that the only force acting on the object is gravity.

Acceleration due to gravity \(g\) varies slightly over Earth’s surface, so the weight of an object depends on its location and is not an intrinsic property of the object. Weight varies dramatically if we leave Earth’s surface, where on the Moon \(g\approx 1.62\ {\rm m/s^2}\) (about 1/6 of the value on Earth’s surface). A \(1\)-kg weight has a weight of \(9.8\ {\rm N}\) on Earth, while it is only \(1.6\ {\rm N}\) on the Moon.

Note

Weight and mass are different physical quantities, although they are closely related.

Mass is an intrinsic property of an object: it is a quantity of matter. In most situations, mass does not vary; therefore its response to an applied force does not vary.

Weight is the gravitational force acting on an object, so it does vary depending on gravity. A person at a lower elevation in New Orleans (i.e., closer to Earth’s center) weighs more than someone at high elevation like on top of Mt. Everest (i.e., farther from Earth’s center) even though they have the same mass.

Why does it feel comfortable to equate mass and weight?

On Earth, we see that weight \(\vec{w}\) is directly proportional to mass \(m\), since \(\vec{w} = m\vec{g}\). When two quantities are proportional, we develop heuristics to communicate more effectively among people with a shared sense of the heuristic.

Suppose you are asked how far is Dallas, TX from Commerce, TX. You might reply that it is about \(1\)-hr, depending on traffic. This makes sense because you and your interlocutor both share in the assumption that you will travel by car at about \(60\ {\rm mph}\). It is important to note that time is not equal to distance, where you are communicating \(x = vt\), where \(x\) is proportional to \(t\) because of the implicit assumption that \(v\) is a constant.

The Earth rotates once every \(24\)-hr, which means that is about \(15^\circ\) per hour. Astronomers developed a measure of distance on the sky called right ascension based on the seemingly constant rotation speed. As a result, it carries units in hours, minute, seconds.

5.4.2.1. Example Problem: Lifting a Stone#

Exercise 5.8

The Problem

A farmer is lifting some moderately heavy rocks from a field to plant crops. He lifts a stone that weighs \(40.0\ \text{lb}\) (about \(180\ \text{N}\)). What force does he apply if the stone accelerates upward at a rate of \(1.5\ \text{m/s}^2\)?

The Model

The system consists of the stone, treated as a particle moving only in the vertical direction. Two external forces act on the stone:

the weight of the stone acting downward, and

the upward force applied by the farmer.

The acceleration is upward, so the net force on the stone must also be upward. Air resistance is neglected.

The Math

The weight of the stone is given, but Newton’s second law requires the mass. We therefore begin by using the definition of weight,

Solving for the mass gives

Substituting the given values,

Next, we apply Newton’s second law in the vertical direction. Taking upward as the positive direction, the net force is the applied force minus the weight,

Newton’s second law gives

so the applied force is

The Conclusion

The farmer applies an upward force of approximately \(F = 210\ \text{N}.\)

This force must be greater than the weight of the stone because the stone is accelerating upward. If the applied force were equal to the weight, the net force would be zero and the stone would move at constant velocity instead of accelerating.

This example reinforces that Newton’s second law depends on the net force, not on any single force acting on an object, and that additional equations such as the definition of weight may be required to complete a dynamics analysis.

The Verification The calculation is verified numerically by computing the mass from the given weight and then applying Newton’s second law to recover the required applied force. A free-body diagram is also generated to confirm that the net force is upward, consistent with the stated upward acceleration.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

w = 180.0 # N

g = 9.81 # m/s^2

a = 1.5 # m/s^2

# Mass

m = w/g

# Applied force

F = m*a + w

print(f"Mass of stone = {m:.2g} kg")

print(f"Applied force = {F:.2g} N")

# --- Free-body diagram ---

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note):

ax.plot(0.0, 0.0, "b.", markersize=17)

for Fvec, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = Fvec

ax.annotate("", xy=(Fx, Fy), xytext=(0.0, 0.0),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(Fy) > abs(Fx):

ax.text(Fx, Fy + 0.15*np.sign(Fy), lab,fontsize=14, ha="center", va="center")

else:

ax.text(Fx + 0.15*np.sign(Fx), Fy, lab,fontsize=14, ha="center", va="center")

ax.set_aspect("equal")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.set_xlim(-1, 1)

ax.set_ylim(-2.5, 2.5)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes,

fontsize=12, va="top")

# Scaled forces for plotting

forces = [np.array([0.0, 1.2]), # applied force

np.array([0.0, -1.0]) # weight

]

labels = [r"$\vec{F}$", r"$\vec{w}$"]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(4, 4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, r"Stone accelerating upward: $\sum \vec{F} = m\vec{a}$")

ax.text(0.25,-0.5, f"$w = %2i\ N$" % w,fontsize=14)

ax.text(0.25,0.5, f"$F = %2i\ N$" % F,fontsize=14)

ax.axhline(0,0,1,linestyle='--', color='k')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Mass of stone = 18 kg

Applied force = 2.1e+02 N

5.5. Newton’s 3rd Law#

Newton’s 3rd Law of Motion

Whenever one body exerts a force on a second body, the first body experiences a force that is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Mathematically, if a body \(A\) exerts a force \(\vec{F}\) on body \(B\), then \(B\) simultaneously exerts a force \(-\vec{F}\) on \(A\), or in vector equation form,

Newton’s 3rd law represents a certain symmetry in nature: Forces always occur in pairs, and one body cannot exert a force on another without experiencing a force itself. We sometimes refer to this law loosely as “action-reaction”.

Consider a swimmer pushing off the side of a pool (see Fig. 5.12). She pushes against the pool wall with her feet and accelerates in the opposite direction of her push. The wall has exerted an equal and opposite force on the swimmer.

Fig. 5.12 Image Credit: Openstax#

You might think that two equal and opposite forces would cancel, but they do not because they act on different systems. In this case, there are two systems that we could investigate: (a) the swimmer and (b) the wall.

(a) If we select the swimmer, then \(\vec{F}_\text{wall on feet}\) is an external force on this system and affects the swimmer’s motion. The swimmer moves in the direction of this force.

(b) The force \(\vec{F}_\text{feet on wall}\) acts on the wall and thus, it does not directly affect the motion of the swimmer and does not cancel \(\vec{F}_\text{wall on feet}\).

The swimmer pushes in the direction opposite that in which she wishes to move. The reaction to her push is thus in the desired direction. In a free-body diagram, we never include both forces of an action-reaction pair, we only use \(\vec{F}_\text{wall on feet}\), not \(\vec{F}_\text{feet on wall}\).

Other examples of Newton’s 3rd law are easy to find:

A car accelerates forward because the ground pushes forward on the drive wheels, in reaction to the drive wheels pushing backward on the ground.

Rockets move forward by expelling gas backward at high velocity. This reaction force is called thrust, which pushes a body forward in response to a backward force.

Helicopters create lift by pushing air down, thereby experiencing an upward reaction force.

There are two important features of Newton’s 3rd law.

The forces exerted (action and reaction) are always equal in magnitude but opposite in direction.

These forces are acting on different bodies or systems: \(A\)’s force acts on \(B\) and \(B\)’s force on A. They don’t act on the same body and thus, they do not cancel each other.

A person who is walking or running applies Newton’s 3rd law instinctively. For example, a runner pushes backward on the ground so that it pushes him forward (see Fig. 5.13).

Fig. 5.13 Image Credit: Openstax#

5.5.1. Example Problem: Forces on a Stationary Object#

Exercise 5.9

The Problem

The package in Figure 5.14 is sitting on a scale. For the scale and package at rest (i.e., not accelerating), show that the scale indicates the weight of the package.

Fig. 5.14 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

The system is the package. The package is modeled as a particle and is stationary in an inertial reference frame. Only vertical forces act on the package.

The Earth exerts a gravitational force on the package directed downward. The scale exerts a contact force on the package directed upward. No horizontal forces act, and air resistance is neglected.

Because the package is at rest, its acceleration is zero.

The Math

Newton’s 2nd law relates the net external force acting on a system to its acceleration. In vector form,

Since the package is not accelerating,

The forces acting on the package are the upward force exerted by the scale and the downward gravitational force. These are written as

The force balance becomes

Substituting the expressions for the forces gives

Factoring out the unit vector,

This requires the scalar magnitudes to satisfy

The Conclusion

The scale reading equals the magnitude of the gravitational force acting on the package. Because the package is stationary, the upward contact force exerted by the scale exactly balances the downward weight. This result shows that a scale measures a contact force, and that this force equals the weight only when the object is not accelerating.

The Verification

The verification numerically confirms that the upward and downward forces cancel when the package is at rest.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Schematic magnitudes (chosen for clean geometry, not to scale)

w = 1.0

s = 1.0

# Forces on the PACKAGE (system = package)

S_on_pkg = np.array([0.0, +s]) # scale on package

W_on_pkg = np.array([0.0, -w]) # Earth on package

Fnet_pkg = S_on_pkg + W_on_pkg

# Forces on the SCALE (system = scale)

minusS_on_scale = np.array([0.0, -s]) # package on scale

minusW_on_scale = np.array([0.0, +w]) # Earth/ground on scale (support)

Fnet_scale = minusS_on_scale + minusW_on_scale

print(f"Net force on package (N): [{Fnet_pkg[0]:.2g}, {Fnet_pkg[1]:.2g}]")

print(f"Net force on scale (N): [{Fnet_scale[0]:.2g}, {Fnet_scale[1]:.2g}]")

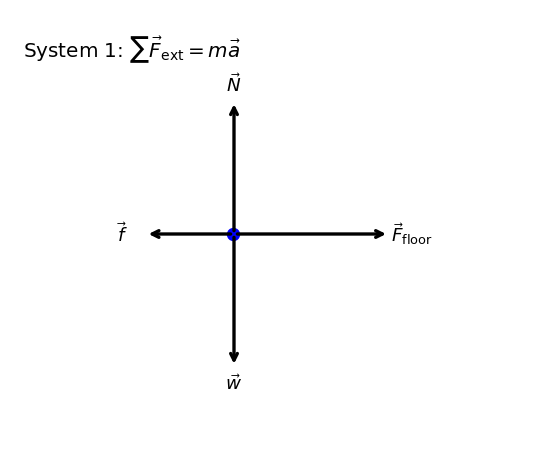

5.5.2. Example Problem: Force on the Cart (Part 1)#

Exercise 5.10

The Problem

A physics professor pushes a cart of demonstration equipment to a lecture hall (Figure 5.15). Her mass is \(65\ {\rm kg}\), the cart’s mass is \(12\ {\rm kg}\), and the equipment’s mass is \(7\ {\rm kg}\). Calculate the acceleration produced when the professor exerts a backward force of \(150\ {\rm N}\) on the floor. All forces opposing the motion, such as friction on the cart’s wheels and air resistance, total \(24.0\ {\rm N}\).

Fig. 5.15 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

The system is the professor, the cart, and the equipment moving together as one object (System 1). Motion is horizontal, so we model the acceleration as one-dimensional along \(\hat{i}\).

The floor exerts a forward force on the system because the professor pushes backward on the floor. Forces opposing the motion (wheel friction and air resistance) act backward on the system with a given total magnitude.

Vertical forces (weight and normal forces) balance so there is no vertical acceleration. Forces between the professor and the cart are internal to the chosen system and do not affect the net external force on the system.

The Math

Newton’s second law relates the net external force on a system to its acceleration,

Because the motion is along the horizontal direction, we write the horizontal force balance in terms of scalar components,

The forward external force on the system is the force from the floor. We represent it as a vector in the \(+\hat{i}\) direction,

The forces opposing the motion act in the \(-\hat{i}\) direction, so we write

The net external force is the sum of the external forces along \(\hat{i}\),

This means the horizontal component satisfies

The total mass of the system is the sum of the professor, cart, and equipment masses,

The given forces are \(F_{\rm floor}=150\ {\rm N}\) and \(f=24.0\ {\rm N}\), so the net external force magnitude is

Solving for the acceleration gives

The Conclusion

The system (professor + cart + equipment) accelerates forward at \(1.5 {\rm m/s^2}\). This result follows because the only horizontal external forces on the chosen system are the forward force from the floor and the backward resistive forces. Internal forces between the professor and the cart cancel within the system and do not affect the net external force.

The Verification

The verification recomputes the net force and acceleration numerically using the given masses and forces. A free-body diagram for System 1 is also drawn using the same draw_fbd function used in the earlier problems.

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

m_prof = 65.0 # kg

m_cart = 12.0 # kg

m_eq = 7.0 # kg

F_floor = 150.0 # N

f = 24.0 # N

m = m_prof + m_cart + m_eq

F_net = F_floor - f

a = F_net / m

print(f"Total mass m = {m:.2g} kg")

print(f"Net external force F_net = {F_net:.3g} N")

print(f"Acceleration a = {a:.2g} m/s^2")

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note, chain_label=r"$\vec{T}$"):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

x0, y0 = 0.0, 0.0

x_chain, y_chain = 0.0, 0.0

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = float(F[0]), float(F[1])

if lab == chain_label:

ax.annotate("", xy=(x_chain + Fx, y_chain + Fy), xytext=(x_chain, y_chain),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

ax.text(x_chain + 0.5*Fx, y_chain + 0.5*Fy + 0.18, lab, fontsize=11,horizontalalignment="center")

x_chain += Fx

y_chain += Fy

continue

ax.annotate("", xy=(x0 + Fx, y0 + Fy), xytext=(x0, y0),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy):

xlab = x0 + Fx + 0.2*np.sign(Fx)

ylab = y0 + Fy

else:

xlab = x0 + Fx

ylab = y0 + Fy + 0.15*np.sign(Fy)

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment="center",

verticalalignment="center")

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-2.0, 2.8)

ax.set_ylim(-2.0, 2.0)

# FBD (System 1): include all forces shown in the diagram

F_floor_plot = 1.4

f_plot = 0.8

N_plot = 1.2

w_plot = 1.2

forces = [

np.array([+F_floor_plot, 0.0]),

np.array([-f_plot, 0.0]),

np.array([0.0, +N_plot]),

np.array([0.0, -w_plot]),

]

labels = [

r"$\vec{F}_{\rm floor}$",

r"$\vec{f}$",

r"$\vec{N}$",

r"$\vec{w}$",

]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, r"System 1: $\sum \vec{F}_{\rm ext}=m\vec{a}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Total mass m = 84 kg

Net external force F_net = 126 N

Acceleration a = 1.5 m/s^2

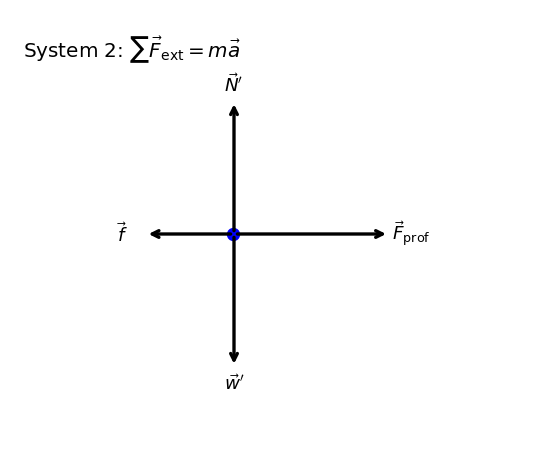

5.5.3. Example Problem: Force on the Cart (Part 2)#

Exercise 5.11

The Problem

Calculate the force the professor exerts on the cart in Figure 5.15, using data from the previous example if needed.

The Model

We define the system of interest to be the cart plus the equipment (System 2). The professor’s push on the cart is now an external force on this system, so it appears in Newton’s second law for System 2.

Motion is horizontal, so we model the acceleration as one-dimensional along \(\hat{i}\). The forces opposing the motion (wheel friction and air resistance) are treated as a single external resistive force of magnitude \(24.0\ {\rm N}\) acting in the \(-\hat{i}\) direction. Vertical forces balance, so \(a_y=0\).

The Math

Newton’s second law in vector form is

For System 2, the horizontal external forces are the professor’s push on the cart and the resistive force. We write these forces as vectors along \(\hat{i}\):

The net external force on System 2 is then

Since the acceleration is along \(\hat{i}\), the scalar component equation is

We want \(F_{\rm prof}\), so we solve for it:

The mass of System 2 is the cart plus the equipment,

From the previous example, the acceleration of the whole group is

The resistive force is

Substituting gives

With significant figures based on the given measurements, the result is

The Conclusion

The professor exerts a forward force of \(53\ {\rm N}\) on the cart (System 2). This is smaller than the \(150\ {\rm N}\) force involved at the floor in the previous example because that larger interaction accelerates the professor as well. Choosing a smaller system changes which forces are external, and it changes what force you are solving for.

The Verification

The verification recomputes \(F_{\rm prof}=ma+f\) using the given masses and the previously found acceleration, and it draws the free-body diagram for System 2 showing \(\vec{F}_{\rm prof}\) to the right and \(\vec{f}\) to the left (with vertical forces included for completeness).

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values (from the previous example, as needed)

m_cart = 12.0 # kg

m_eq = 7.0 # kg

a = 1.5 # m/s^2

f = 24.0 # N

m = m_cart + m_eq

F_net = m*a

F_prof = F_net + f

print(f"System 2 mass m = {m:.3g} kg")

print(f"Net force needed (ma) = {F_net:.2g} N")

print(f"Professor's force on cart F_prof = {F_prof:.2g} N")

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note, chain_label=r"$\vec{T}$"):

ax.plot(-0.01, 0.0, "bo", markersize=7)

x0, y0 = 0.0, 0.0

x_chain, y_chain = 0.0, 0.0

for F, lab in zip(forces, labels):

Fx, Fy = float(F[0]), float(F[1])

if lab == chain_label:

ax.annotate("", xy=(x_chain + Fx, y_chain + Fy), xytext=(x_chain, y_chain), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

ax.text(x_chain + 0.5*Fx, y_chain + 0.5*Fy + 0.18, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment="center")

x_chain += Fx

y_chain += Fy

continue

ax.annotate("", xy=(x0 + Fx, y0 + Fy), xytext=(x0, y0), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2))

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy):

xlab = x0 + Fx + 0.2*np.sign(Fx)

ylab = y0 + Fy

else:

xlab = x0 + Fx

ylab = y0 + Fy + 0.15*np.sign(Fy)

ax.text(xlab, ylab, lab, fontsize=11, horizontalalignment="center",verticalalignment="center")

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.02, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

ax.set_xlim(-2.0, 2.8)

ax.set_ylim(-2.0, 2.0)

# --- Free-body diagram (System 2): include all forces shown for the system ---

F_prof_plot = 1.4

f_plot = 0.8

N_plot = 1.2

w_plot = 1.2

forces = [

np.array([+F_prof_plot, 0.0]),

np.array([-f_plot, 0.0]),

np.array([0.0, +N_plot]),

np.array([0.0, -w_plot]),

]

labels = [

r"$\vec{F}_{\rm prof}$",

r"$\vec{f}$",

r"$\vec{N}'$",

r"$\vec{w}'$",

]

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, r"System 2: $\sum \vec{F}_{\rm ext}=m\vec{a}$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

System 2 mass m = 19 kg

Net force needed (ma) = 28 N

Professor's force on cart F_prof = 52 N

5.5.4. Check Your Understanding#

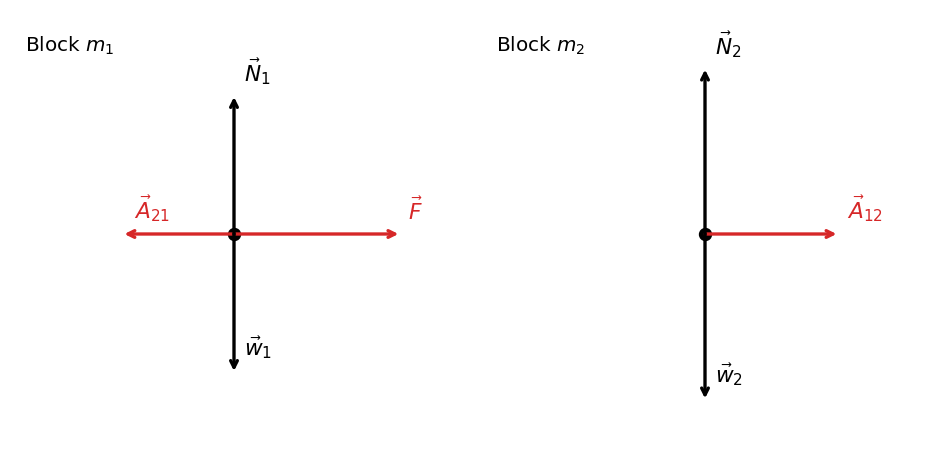

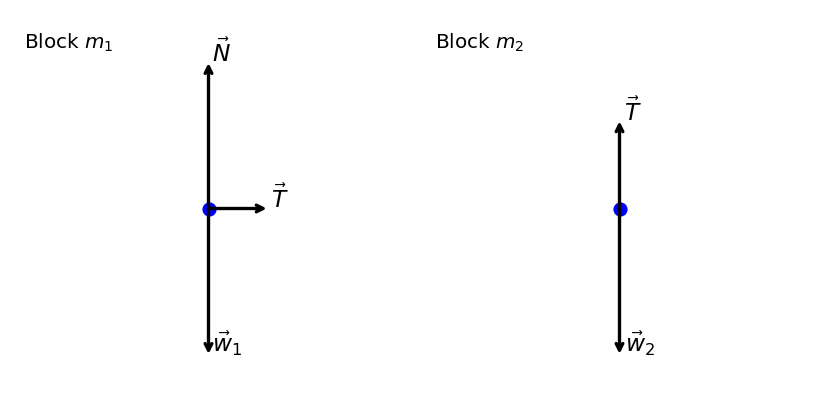

Two blocks are at rest and in contact on a frictionless surface, with \(m_1 = 2\ {\rm kg}\), \(m_2 = 6\ {\rm kg}\), and applied force \(24\ {\rm N}\).

(a) Find the acceleration of the system of blocks.

(b) Suppose that the block are later separated. What force will give the second block, with the mass of \(6\ {\rm kg}\), the same acceleration as the system of blocks?

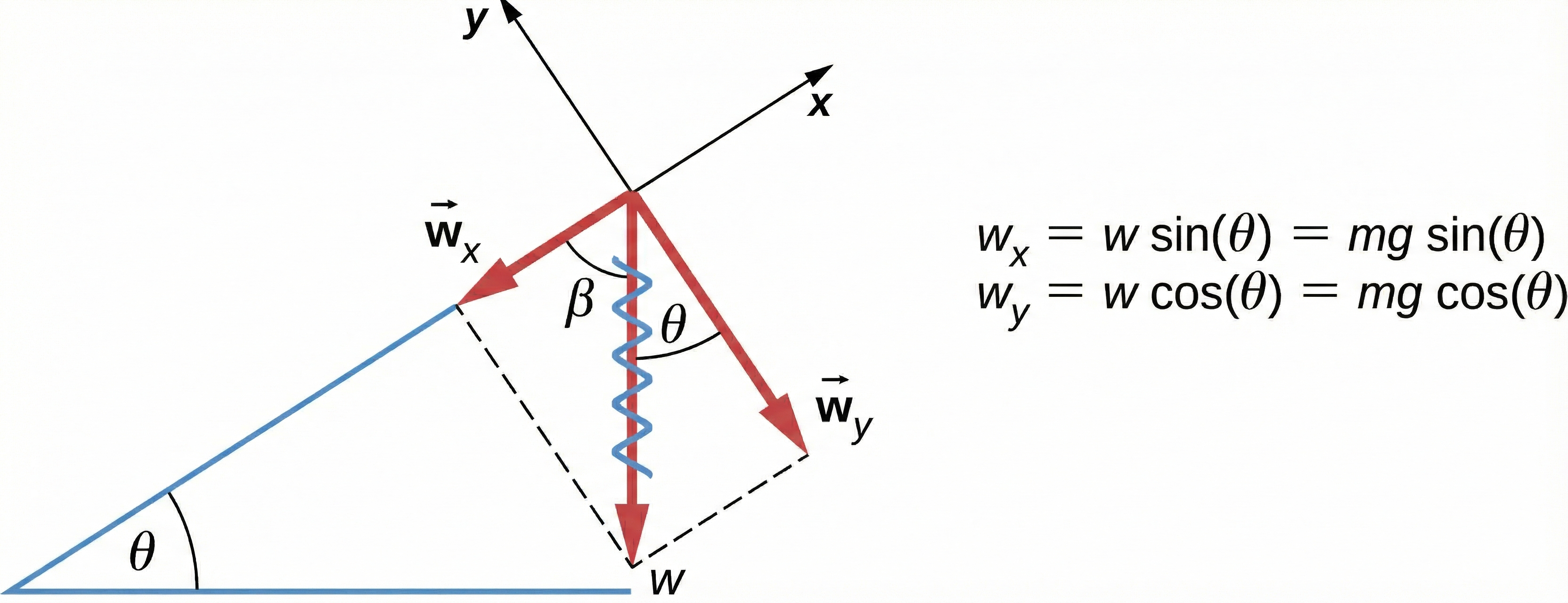

5.6. Common Forces#

5.6.1. Normal Force#

Weight is a pervasive force that acts at all times and must be counteracted to keep an object from falling (i.e., in static equilibrium). You must support the weight of a heavy object by pushing up on it when you hold it stationary.

When a bag of dog food is placed on the table (see Fig. 5.16), the table sags slightly under the load. This is more noticeable on a card table, compared to a sturdy oak table. Unless an object is deformed beyond its limit, it will exert a restoring force like a spring. The greater the deformation, the greater the restoring force. The next external force on the load is zero, when the load is stationary on the table.

Fig. 5.16 Image Credit: Openstax#

Whatever supports a load must supply an upward force equal to the weight of the load. If the force supporting the weight of an object is perpendicular to the surface of contact, this is defined as a normal force \(\vec{N}\). This means that the normal force experienced by an object resting on a horizontal forced can be expressed in vector form and scalar form as:

Note

One must be careful to not confuse the scalar magnitude of the normal force \(N\) with the unit of force, the newton \(\rm N\).

The normal force can be less than the object’s weight, if the object is on an incline.

When an object rests on an incline that makes an angle \(\theta\) with the horizontal, the force of gravity acting on the object is divided into two components:

a force acting perpendicular to the plane, \(w_y\), and

a force acting parallel to the plane, \(w_x\).

The normal force \(\vec{N}\) is typically equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to \(w_y\), where the component parallel to the plane \(w_x\) causes the object to accelerate down the incline (see Fig. 5.17). The \(w_x\) is the unbalanced force which allows the acceleration to occur, where \(w_y\) is balanced by the normal force \(N\).

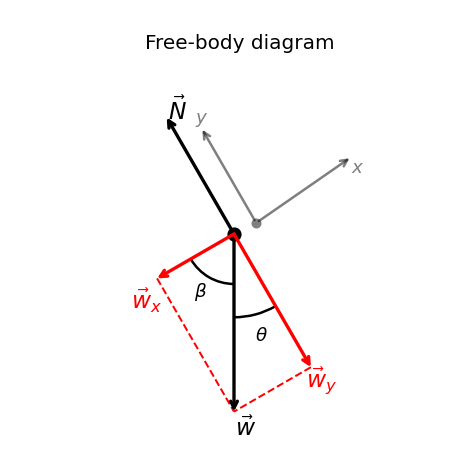

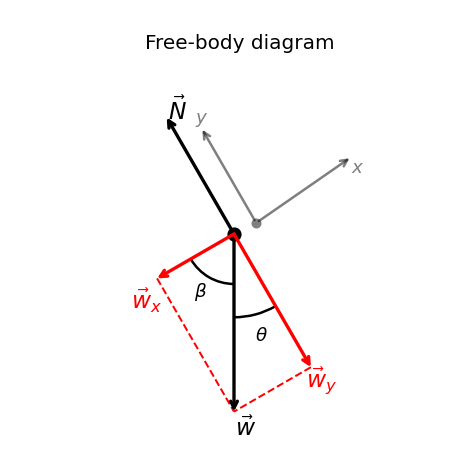

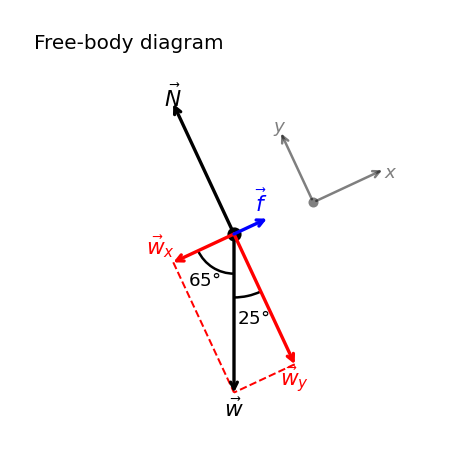

Fig. 5.17 The coordinate system is chosen so that the \(x\)-axis is parallel to the inclined surface. The angle \(\beta (= 90^\circ - \theta)\) is complementary to \(\theta\). Modified from OpenStax Figure 5.23.#

Angles on a Triangle

How do we know that the angle \(\theta\) given in Fig. 5.17 is the same in both places?

Let’s assume that they are different:

\(\theta_1\) is the angle between between \(\vec{w}\) and \(\vec{w}_y\),

\(\theta_2\) is the angle between the horizontal surface and incline plane.

The angle between \(\vec{w}\) and \(\vec{w}_x\) is \(\beta = 90^\circ - \theta_1\) because \(\vec{w}_x\) and \(\vec{w}_y\) are perpendicular. The inclined surface also makes a triangle, with 3 angles that sum to \(180^\circ\), or

We can solve for \(\beta\) in terms of \(\theta_2\) and substitute into the equation for the equation with \(\theta_1\),

With a little geometry, we showed that \(\theta_1 = \theta_2 = \theta\).

Be careful when resolving the weight into components. Normally when the \(x\)-component of a force \(\vec{F}\) is resolved, we find that \(F_x = F\cos{\theta}\). However, in this case we are using the complementary angle \(\beta = 90^\circ - \theta\) to resolve the \(w_x\). Using the red vectors in Fig. 5.17, we have

We can sum the forces along the \(y\)-axis to write the magnitude of the normal force experienced by an object resting on an inclined plane:

Notice that the force components and normal force could be determined from a free-body diagram.

Fig. 5.18 Free-body diagram showing \(\vec{w}\) resolved into \(\vec{w}_x\) and \(\vec{w}_y\) in axes aligned with the incline.#

Show code cell content

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.patches import Arc

from myst_nb import glue

# -----------------------------

# Parameters

# -----------------------------

theta = np.deg2rad(30.0) # incline angle

w = 1.6 # weight magnitude (plot units)

N = 1.4*np.cos(theta) # normal force magnitude (plot units)

# Weight components in rotated frame

w_x = w * np.sin(theta)

w_y = w * np.cos(theta)

# -----------------------------

# Helper: angle arc marker

# -----------------------------

def draw_angle_arc(ax, v1, v2, radius=0.6, label=r"$\theta$", label_r=0.75, lw=1.5):

"""

Draw the smaller CCW arc from v1 to v2 (both are 2D direction vectors).

Places a label near the middle of the arc.

"""

def ang_deg(v):

return (np.degrees(np.arctan2(v[1], v[0])) + 360.0) % 360.0

a1 = ang_deg(v1)

a2 = ang_deg(v2)

# CCW sweep from a1 to a2

delta = (a2 - a1) % 360.0

if delta > 180.0:

# Use the smaller arc by swapping

a1, a2 = a2, a1

delta = (a2 - a1) % 360.0

a2_plot = a1 + delta # ensure CCW arc length = delta

arc = Arc((0.0, 0.0), 2*radius, 2*radius, angle=0.0, theta1=a1, theta2=a2_plot, lw=lw)

ax.add_patch(arc)

amid = np.radians(a1 + 0.5*delta)

ax.text(label_r*np.cos(amid), label_r*np.sin(amid), label, fontsize=11,

ha="center", va="center")

# -----------------------------

# Free-body diagram function

# -----------------------------

def draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, note, colors=None):

ax.plot(0, 0, "k.", markersize=15)

if colors is None:

colors = ["black"]*len(forces)

for F, lab, col in zip(forces, labels,colors):

Fx, Fy = F

ax.annotate("",xy=(Fx, Fy),xytext=(0, 0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2,color=col, shrinkA=0, shrinkB=0))

# Label placement

if abs(Fx) > abs(Fy):

ax.text(Fx * 1.05-0.2, Fy-0.2, lab, color=col, ha="left", va="center", fontsize=14)

else:

ax.text(Fx+0.1, Fy * 1.08-0.025, lab, color=col, ha="center", va="center", fontsize=14)

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

ax.text(0.3, 0.95, note, transform=ax.transAxes, fontsize=12, va="top")

# -----------------------------

# Coordinate axes (rotated)

# -----------------------------

x_hat = np.array([np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)])

y_hat = np.array([-np.sin(theta), np.cos(theta)])

# Directions for components (down-slope and into the plane-normal direction)

wx_dir = -x_hat

wy_dir = -y_hat

w_dir = np.array([0.0, -1.0]) # weight direction (down)

# -----------------------------

# Forces

# -----------------------------

forces = [

np.array([0.0, -w]), # weight

np.array([N * y_hat[0], N * y_hat[1]]), # normal force (along +y_hat)

np.array([w_x * wx_dir[0], w_x * wx_dir[1]]), # w_x (along -x_hat)

np.array([w_y * wy_dir[0], w_y * wy_dir[1]]) # w_y (along -y_hat)

]

labels = [r"$\vec{w}$",r"$\vec{N}$",r"$\vec{w}_x$",r"$\vec{w}_y$"]

colors = ["k","k","r","r"]

# -----------------------------

# Plot

# -----------------------------

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

draw_fbd(ax, forces, labels, r"Free-body diagram",colors=colors)

# --- Parallelogram construction (dashed lines) ---

w_tip = forces[0]

wx_tip = forces[2]

wy_tip = forces[3]

ax.plot([wx_tip[0], w_tip[0]],[wx_tip[1], w_tip[1]],

linestyle="--", linewidth=1.2, color="red")

ax.plot([wy_tip[0], w_tip[0]],[wy_tip[1], w_tip[1]],

linestyle="--", linewidth=1.2, color="red")

# Draw coordinate axes

x_offset, y_offset = 0.2,0.1

ax.annotate("", xy=(x_hat[0]+x_offset, x_hat[1]+0.2), xytext=(x_offset, y_offset),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,alpha=0.5))

ax.text(1.1*x_hat[0]+0.1, 1.1*x_hat[1], r"$x$", fontsize=11,alpha=0.5)

ax.annotate("", xy=(y_hat[0]+x_offset, y_hat[1]+0.1), xytext=(x_offset, y_offset),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,alpha=0.5))

ax.text(1.1*y_hat[0]+x_offset, 1.1*y_hat[1]+y_offset/2, r"$y$", fontsize=11,alpha=0.5)

ax.plot(x_offset,0.1,'.',color='gray',ms=10)

# -----------------------------

# Angle markers