2. Vectors#

2.1. Scalars and Vectors#

2.1.1. What is a scalar?#

A scalar defines the amount of something in one dimension. They are accompanied by a unit which signifies the dimension in particular. We learn amount dimensions as a concept of length (e.g., meters), but a dimension can be generally described as one aspect of a thing.

Fig. 2.1 Image Credit: Wikipedia.#

For example, your car (see Figure 2.1) has multiple dimensions:

mass –> \(1500\ {\rm kg}\)

age –> \(4\ {\rm yr}\)

gas tank –> \(10\ {\rm gal}\)

gas mileage –> \(40\ {\rm mpg}\)

Each of these dimensions for describing the car has a number followed by the unit, which makes up the scalar quantity.

2.1.2. Scalar arithmetic#

Scalar quantities can only be combined (or separated) when the have the same unit. For example, a \(50\)-\({\rm min}\) class that ends \(10\ {\rm min}\) early lasts for \(50\ {\rm min} - 10\ {\rm min} = 40\ {\rm min}\).

If you were told that the class ended \(600\ {\rm sec}\) early, you cannot combine (or separate) the quantities directly. Instead, you must first convert to a common unit, then you can proceed as before.

Note

You can write in math mode using $ $ or using the \begin{align} \end{align} environment. See the source of this notebook (rocketship on Google Colab) for more details.

class_time = 50 #class time in minutes

early_time = 600 #amount of time early (in sec)

# must convert the early time from sec -- > min

class_time_early = class_time - (early_time/60)

print("The class ends %2.0f minutes early." % class_time_early)

The class ends 40 minutes early.

Scalars can also be multiplied and divided, where units can be combined under the appropriate operation. For example, energy is described by the amount of force applied (i.e. multiplied) over a distance, or \(E = Fd\).

Suppose you pushed a 0.5-\({\rm kg}\) box with a force of 1 \(\rm Newton\) horizontally across the floor for 5 meters (see Figure 2.2). Then, you expended \(5\ {\rm N\cdot }m\) of energy. The unit is combined to form a Newton-meter, or \(\rm Joule\).

Fig. 2.2 Image Credit: stickmanphysics.com.#

If you traveled to Dallas from Commerce (\({\sim}60\ {\rm mi}\) away) in your car and the trip took \(1\ {\rm h}\). Then your average speed has is a derived scalar quantity of \(60\ {\rm mi/h}\).

2.1.3. What is a vector?#

A vector combines scalar quantities as a new object that delineates the quantities by their dimension. A unit vector represents a single step along a dimensional axis and is signified using the hat (or \(\hat{}\)) symbol over the variable for that axis. For example, 1 unit step along the x-axis is represented by \(\hat{x}\), which can be written as $\hat{x}$ a the text cell in your Jupyter notebook.

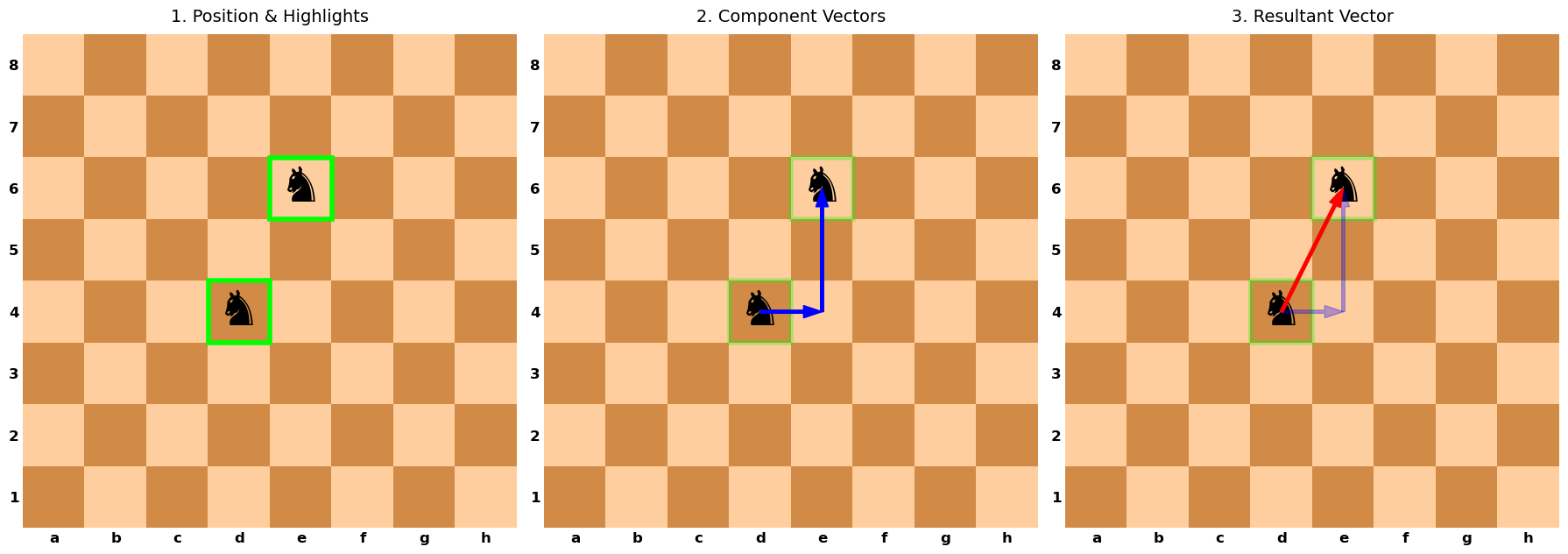

Consider a chessboard, where players designate letters and numbers to identify a piece at a particular location on the board. The chess pieces move as vectors to traverse the chessboard.

The knight moves in an \(L\)-shaped pattern that can include moving the piece either: one space horizontally, 2 spaces vertically or 2 spaces horizontally, 1 space vertically. Both of these choices represent a vector when we consider the initial and final locations of the knight.

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from matplotlib.colors import ListedColormap

import matplotlib.patches as patches

def draw_vector_panels():

# 1. Setup Data and Colors

dx, dy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(8), np.arange(8))

board_grid = (dx + dy) % 2

dark_color = '#D18B47'

light_color = '#FFCE9E'

cmap = ListedColormap([dark_color, light_color])

files = ['a', 'b', 'c', 'd', 'e', 'f', 'g', 'h']

ranks = ['1', '2', '3', '4', '5', '6', '7', '8']

# Vector/Piece Coordinates

x0, y0 = 3., 3. # Start at d4

kx, ky = 1, 2 # Knight move (1 right, 2 up)

# 2. Create Subplots (1 Row, 3 Cols)

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(18, 6))

# Helper function to draw the base board on any given axis

def setup_board(ax):

ax.imshow(board_grid, cmap=cmap, origin='lower')

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(8))

ax.set_xticklabels(files, fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.set_yticks(np.arange(8))

ax.set_yticklabels(ranks, fontsize=12, weight='bold')

ax.tick_params(axis='both', which='both', length=0)

# Clean borders

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

# Place Pieces (Knights)

# Using ha='center' aligns the text automatically to the grid center

ax.text(x0, y0, '♞', color='k', fontsize=40, ha='center', va='center')

ax.text(x0+kx, y0+ky, '♞', color='k', fontsize=40, ha='center', va='center')

# --- PANEL 1: Pieces + Border Highlights ---

ax1 = axes[0]

setup_board(ax1)

ax1.set_title("1. Position & Highlights", fontsize=14, pad=10)

# Add Highlights (Rectangles around start and end cells)

# Note: (x-0.5, y-0.5) is the bottom-left corner of a cell centered at (x,y)

rect_start = patches.Rectangle((x0-0.5, y0-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4)

rect_end = patches.Rectangle((x0+kx-0.5, y0+ky-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4)

ax1.add_patch(rect_start)

ax1.add_patch(rect_end)

# --- PANEL 2: Add Component Vectors (Blue) ---

ax2 = axes[1]

setup_board(ax2)

ax2.set_title("2. Component Vectors", fontsize=14, pad=10)

# Keep highlights (optional, for continuity)

ax2.add_patch(patches.Rectangle((x0-0.5, y0-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4, alpha=0.3))

ax2.add_patch(patches.Rectangle((x0+kx-0.5, y0+ky-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4, alpha=0.3))

# Blue Arrows

# Horizontal component

ax2.arrow(x0, y0, kx, 0, color='b', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2, zorder=5)

# Vertical component (starts where horizontal ended)

ax2.arrow(x0+kx, y0, 0, ky, color='b', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2, zorder=5)

# --- PANEL 3: Add Resultant Vector (Red) ---

ax3 = axes[2]

setup_board(ax3)

ax3.set_title("3. Resultant Vector", fontsize=14, pad=10)

# Ghost previous elements

ax3.add_patch(patches.Rectangle((x0-0.5, y0-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4, alpha=0.3))

ax3.add_patch(patches.Rectangle((x0+kx-0.5, y0+ky-0.5), 1, 1, fill=False, edgecolor='#00FF00', linewidth=4, alpha=0.3))

ax3.arrow(x0, y0, kx, 0, color='b', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2, zorder=5, alpha=0.3)

ax3.arrow(x0+kx, y0, 0, ky, color='b', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2, zorder=5, alpha=0.3)

# Red Resultant Arrow

ax3.arrow(x0, y0, kx, ky, color='r', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2, zorder=6)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

if __name__ == "__main__":

draw_vector_panels()

A vector is also described as an object that has both magnitude and direction (see Figure 2.3).

Fig. 2.3 Victor “Vector” Perkins demonstrating that he has both magnitude and direction. Image Credit: Illumination: Despicable Me.#

Physical quantities specified by giving a number of units (i.e., magnitude) and a direction (i.e., angle or up/down/left/right) are called vector quantities. Examples include:

position,

displacement (change in position),

velocity (change in position per time),

acceleration (change in velocity per time),

force,

torque.

Vectors can be combined together to make a new vector or multiplied by a scalar to create a vector of a new length. The chessboard example above showed the resultant vector is composed by the addition of two component vectors.

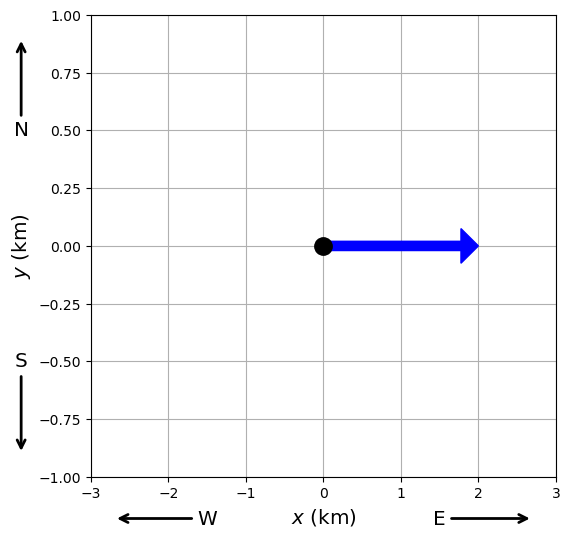

Vectors are distinguished from scalars using an arrow over the variable. Suppose we can identify the position vector of an object because it is \(2\ {\rm km}\) due east, then we can write the vector \(\vec{m} = 2 \hat{x}\ {\rm km}\), where \(\hat{x}\) represents the direction due east or along the positive x-axis. The \(\hat{x}\) is a unit vector with a length equal to 1.

Note

In your Jupiter notebook Markdown (text) cell, the \(\vec{m}\) is represented by $\vec{m}$, and the \(\hat{x}\) is represented by $\hat{x}$. Be sure to use The $ $ around your LaTeX symbols so they render properly. Click the link to see a cheat sheet for LaTeX commands.

The object \(\vec{m}\) is a vector because it has a magnitude (\(2\ {\rm km}\)) and a direction (\(\hat{x}\)). The magnitude can be written equivalently as \(m \equiv |\vec{m}|\)

What is the vector for an object that is \(2\ {\rm km}\) due west?

What is the vector for an object that is \(2\ {\rm km}\) due north/south?

Note that we have chosen the \(x\) in \(\hat{x}\) arbitrarily, where we could have used any other symbol. You might see that other textbooks use \(\hat{i}\) instead. If you dealing with a vector with an unknown magnitude in the positive \(x\) direction, then you can see where \(\vec{m} = x \hat{i}\) could be useful.

See the python script below, where it shows how to represent the vector \(\vec{m}= 2\hat{x}\) using the plotting library matplotlib.

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2)

#create m-vector using python

x0,y0,dx,dy = 0,0,2,0

ax.arrow(x0,y0,dx,dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.15,zorder=4)

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

# -------------------------------------------------

# Cardinal arrows in whitespace near x-axis label

# -------------------------------------------------

arrow_kw = dict(arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='->', lw=2),

xycoords='axes fraction',

textcoords='axes fraction', fontsize='x-large',

zorder=6)

# East arrow (+x, right)

ax.annotate('E', xy=(0.95, -0.09), xytext=(0.75, -0.09),

ha='center', va='center', **arrow_kw)

# West arrow (-x, left)

ax.annotate('W',xy=(0.05, -0.09), xytext=(0.25, -0.09),

ha='center', va='center', **arrow_kw)

# North arrow (+y, up)

ax.annotate('N',xy=(-0.15, 0.95), xytext=(-0.15, 0.75),

ha='center', va='center', **arrow_kw)

# South arrow (-y, down)

ax.annotate('S',xy=(-0.15, 0.05), xytext=(-0.15, 0.25),

ha='center', va='center', **arrow_kw)

ax.set_xlim(-3, 3)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 1)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

You can use the python code below as a template to plot your vectors in this chapter. Be sure to modify the limits/labels as needed.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2)

#create vector using python

x0,y0,dx,dy = 0,0,2,0

ax.arrow(x0,y0,dx,dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.15,zorder=4)

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.set_xlim(-3, 3)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 1)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

In general, we define \(\vec{D}\) as the displacement vector, where it measures the change in a position vector. The displacement vector can be the resultant vector of two other vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\). Figure 2.4 shows how these 2 vectors can be oriented relative to each other.

Fig. 2.4 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

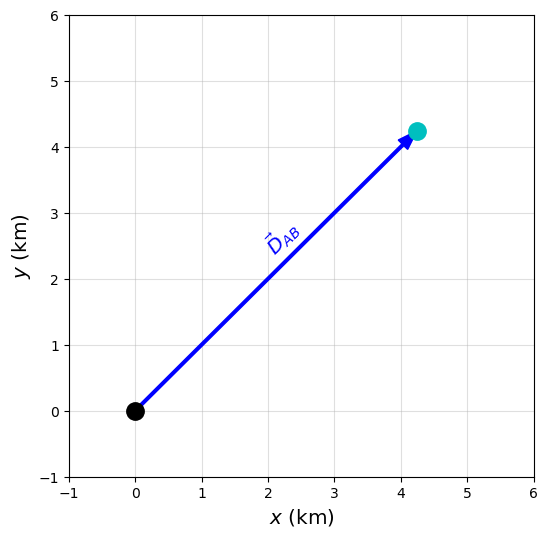

Suppose that you’re walking from your tent at position \(A\) and going to a pond at position \(B\). It’s easier to keep track of your displacement \(\vec{D}\) by using subscripts denoting the intended source location and final destination (see Figure 2.5).

Fig. 2.5 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

Mathematically, \(\vec{D}_{AB}\) represents the displacement vector from \(A\) to \(B\), where the opposite \(\vec{D}_{BA} = -\vec{D}_{AB}\) because you would only need to walk in the opposite (\(-\)) direction. We can also say that \(\vec{D}_{BA}\) is antiparallel to \(\vec{D}_{AB}\).

Two vectors that have identical directions are parallel to each other.

Two vectors that are perpendicular to each other are also said to be orthogonal vectors.

2.1.4. Algebra of Vectors in 1D#

Fig. 2.6 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

Figure 2.6 shows three scenarios for your friend who walks from the campsite to the fishing pond. He wants to walk from point A to B, or have a displacement vector \(\vec{D}_{AB}\). Let’s see how is vector is modified when he

stops to rest at point C,

realizes that he dropped his prize lure and has to go back to a point D,

continues from point D and arrives at the fishing pond at point B.

The python script below represents the vector \(\vec{D}_{AB}\), where I’ve chosen a \(45^\circ\) angle for illustration only.

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs='x-large'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2,alpha=0.4)

#components of a unit vector u

theta = np.pi/4

ux, uy = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

#Vector D_AB = 6*u

mag_D_AB = 6

x0,y0,dx,dy = 0,0,mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0,y0,dx,dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+mag_D_AB*ux,y0+mag_D_AB*uy,'c.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.text(dx/2-0.25,dy/2+0.25,'$\\vec{D}_{AB}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='b')

ax.set_xlim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

Your friend rests at point C, which is \(3/4\) of the way to the pond. We also know that the full distance from the campsite to the pond is \(6\ {\rm km}\). What is his displacement vector \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) when he stops to rest?

Notice that the vector in panel (a) is not along the x-axis, but in a northeasterly direction. In this question, we apply a unit vector \(\hat{u}\) so that we can define:

There could be some transformation to decompose \(\hat{u}\rightarrow x\hat{i} + y\hat{j}\), but we do not need to know (in this case) as long as we express all other vectors either parallel or antiparallel to \(\hat{u}\).

Do you think \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) is parallel or antiparallel to \(\vec{D}_{AB}\)?

Since your fiend is walking in the direction \(\hat{u}\), his vector at point C is parallel to the path from the campsite to the pond. Then we can scale the original vector by the fraction of the total distance traveled (i.e., \(3/4\) (or \(0.75\)) of the way).

Scaling a vector

To scale a vector, you simply multiply by a scalar (i.e., a number), let’s call it \(\alpha\). If \(\alpha\) is:

\(< 1\), then it shrinks the vector.

\(=1\), then it copies the vector exactly.

\(>1\), then it enlarges the vector.

In all three cases, the direction of the new vector is preserved (i.e., unchanged) relative to the old vector, although the magnitude of the new vector can be different.

We can represent the vector \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) as

Note that we have 2 ways to represent the new vector.

The magnitude of \(\vec{D}_{AB}\) is represented by \(|\vec{D}_{AB}| = 6\ {\rm km}\). We found the second form by multiplying the scalar \(\alpha = 0.75\) by the scalar \(|\vec{D}_{AB}|\). Therefore we know the magnitude of \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) is

In general,

a scalar multiplied by a vector creates a new vector, \(\vec{B} = \alpha\vec{A}\).

a scalar multiplied by a scalar creates a new scalar, \(|\vec{B}| = \alpha|\vec{A}|\).

The python script below represents the vectors \(\vec{D}_{AB}\) and \(\vec{D}_{AC}\), graphically.

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs = 'x-large'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2,alpha=0.4)

#components of a unit vector u

theta = np.pi/4

ux, uy = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

#Vector D_AB = 6*u

mag_D_AB = 6

x0,y0,dx,dy = 0,0,mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0,y0,dx,dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(dx/2-0.25,dy/2+0.25,'$\\vec{D}_{AB}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='b')

#Vector D_AC = 0.75*D_AB

mag_D_AC = 0.75

xshift, yshift = 0.2, -0.2 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,dx,dy = 0,0,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0+xshift,y0+yshift,dx,dy,color='r', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(dx/2+0.35,dy/2-0.35,'$\\vec{D}_{AC}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='r')

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+mag_D_AB*ux,y0+mag_D_AB*uy,'c.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*ux,y0+mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*uy,'r.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.set_xlim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

Your friend now realizes that he dropped his prize lure and has to go back to look for it and finds it at a a point D that is \(1.2\ {\rm km}\) from point C. We can represent his new path as a vector \(\vec{D}_{CD}\).

Do you think \(\vec{D}_{CD}\) is parallel or antiparallel to \(\vec{D}_{AB}\)?

Since he had to retrace his steps, the vector \(\vec{D}_{CD}\) will have a direction that is opposite to \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) (and \(\vec{D}_{AB}\).

We can represent the vector \(\vec{D}_{CD}\) as

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs = 'x-large'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2,alpha = 0.4)

#components of a unit vector u

theta = np.pi/4

ux, uy = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

#Vector D_AB = 6*u

mag_D_AB = 6

x0,y0,AB_dx,AB_dy = 0,0,mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0,y0,AB_dx,AB_dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AB_dx/2-0.25,AB_dy/2+0.25,'$\\vec{D}_{AB}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='b',zorder=4)

#Vector D_AC = 0.75*D_AB

mag_D_AC = 0.75

xshift, yshift = 0.2, -0.2 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,AC_dx,AC_dy = 0,0,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0+xshift,y0+yshift,AC_dx,AC_dy,color='r', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AC_dx/2+0.35,AC_dy/2-0.35,'$\\vec{D}_{AC}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='r')

#Vector D_CD = -0.2*D_AB

mag_D_CD = -0.2

xshift, yshift = -0.2, 0.2 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,CD_dx,CD_dy =0,0,mag_D_CD*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_CD*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(AC_dx+xshift,AC_dy+yshift,CD_dx,CD_dy,color='m', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AC_dx+2*CD_dx/3-0.45,AC_dy+2*CD_dy/3+0.45,'$\\vec{D}_{CD}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='m')

x0,y0 = 0,0

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AB_dx,y0+AB_dy,'c.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AC_dx,y0+AC_dy,'r.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AC_dx+CD_dx,y0+AC_dy+CD_dy,'m.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.set_xlim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

Furthermore, we can represent your friends displacement vector relative to:

the campsite by \(\vec{D}_{AD}\), or

the fishing pond \(\vec{D}_{DB}\).

Since your friend had to turn back, he wants to know which location (campsite or fishing hole) is closer. He’s not much of a hiker, and just wants to go to the closer location.

We can find either vector \(\vec{D}_{AD}\) or \(\vec{D}_{DB}\) using a combination of the vectors we already know. We can deduce \(\vec{D}_{AD}\) by the addition (or difference) of \(\vec{D}_{AB}\) with \(\vec{D}_{AC}\) and \(\vec{D}_{CD}\). Let’s start by defining:

The vector \(\vec{D}_{AD}\) simply represents your friend’s total path accounting for a change in direction. Through substitution, we have

We can find \(\vec{D}_{DB}\) through another deduction by,

Together, we can take the magnitude of each vector to find that

\(|\vec{D}_{AD}| = 3.3\ {\rm km}\) back to the campsite, and

\(|\vec{D}_{AD}| = 2.7\ {\rm km}\) to the pond.

It looks like your friend is going fishing after all.

Does this make sense?

We should expect that \(\vec{D}_{AD} + \vec{D}_{DB} = \vec{D}_{AB}\), which we can see this in our graph.

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs = 'x-large'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,zorder=2,alpha=0.4)

#components of a unit vector u

theta = np.pi/4

ux, uy = np.cos(theta), np.sin(theta)

#Vector D_AB = 6*u

mag_D_AB = 6

x0,y0,AB_dx,AB_dy = 0,0,mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0,y0,AB_dx,AB_dy,color='b', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AB_dx/2-0.25,AB_dy/2+0.25,'$\\vec{D}_{AB}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='b',zorder=4)

#Vector D_AC = 0.75*D_AB

mag_D_AC = 0.75#D_AB

xshift, yshift = 0.2, -0.2 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,AC_dx,AC_dy = 0,0,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AC*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(x0+xshift,y0+yshift,AC_dx,AC_dy,color='r', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AC_dx/2+0.35,AC_dy/2-0.35,'$\\vec{D}_{AC}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='r')

#Vector D_CD = -0.2*D_AB

mag_D_CD = -0.2 #D_AB

xshift, yshift = -0.2, 0.2 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,CD_dx,CD_dy =0,0,mag_D_CD*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_CD*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(AC_dx+xshift,AC_dy+yshift,CD_dx,CD_dy,color='m', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AC_dx+2*CD_dx/3-0.45,AC_dy+2*CD_dy/3+0.45,'$\\vec{D}_{CD}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='m')

#Vector D_AD = D_AC + D_CD

mag_D_AD = 0.55 #D_AB

xshift, yshift = -0.4, 0.4 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,AD_dx,AD_dy =0,0,mag_D_AD*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_AD*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(xshift,yshift,AD_dx,AD_dy,color='orange', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AD_dx/2-0.65,AD_dy/2+0.65,'$\\vec{D}_{AD}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='orange')

#Vector D_DB = D_AB + D_AD

mag_D_DB = 0.45 #D_AB

xshift, yshift = -0.4, 0.4 #shifts onl so the both vectors are visible

x0,y0,DB_dx,DB_dy = 0,0,mag_D_DB*mag_D_AB*ux,mag_D_DB*mag_D_AB*uy

ax.arrow(AC_dx+CD_dx+xshift,AC_dy+CD_dy+yshift,DB_dx,DB_dy,color='purple', ls='-', width=0.04, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.2,zorder=4)

ax.text(AC_dx+CD_dx+DB_dx/3-0.65,AC_dy+CD_dy+DB_dy/3+0.65,'$\\vec{D}_{DB}$',rotation=45,fontsize=fs,color='purple')

x0,y0 = 0,0

ax.plot(x0,y0,'k.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AB_dx,y0+AB_dy,'c.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AC_dx,y0+AC_dy,'r.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.plot(x0+AC_dx+CD_dx,y0+AC_dy+CD_dy,'m.',ms=25,zorder=5)

ax.set_xlim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylim(-1, 6)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (km)',fontsize='x-large')

plt.show()

2.1.5. Properties of vectors#

The resultant vector \(\vec{R}\) of two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\) can be determined by the addition of the two vectors as

When we draw the resultant vector, we place them the tail at the origin and draw to place the head at the final location (i.e., head-to-tail method). In our above example, \(\vec{D}_{AD}\) was the resultant vector of the \(\vec{D}_{AC} + \vec{D}_{CD}\).

In general, vectors have similar properties as scalars. We can:

add any number of vectors in any order, where vector addition is commutative.

\[ \vec{A} + \vec{B} = \vec{B} + \vec{A} \]group the addition of vectors in any order, where vector addition is associative.

\[ (\vec{A} + \vec{B}) + \vec{C} = \vec{A} + (\vec{B} + \vec{C}) \]distribute scalar(s) across vector(s), where vector multiplication is distributive.

(2.9)#\[\begin{align} (\alpha + \beta)\vec{A} &= \alpha \vec{A} + \beta\vec{A}, \\ \alpha(\vec{A}+\vec{B}) &= \alpha \vec{A} + \alpha \vec{B}. \end{align}\]

2.1.5.1. Example Problem: Ladybug walking on a stick#

Exercise 2.1

The Problem

A long measuring stick rests against a wall in a physics laboratory with its 200-cm end at the floor. A ladybug lands at the 100-cm mark and crawls randomly along the stick. It first walks 15 cm toward the floor, then it walks 56 cm toward the wall, then it walks 3 cm toward the floor again. Then, after a brief stop, it continues 25 cm toward the floor and then, again, it crawls 19 cm toward the wall before coming to a complete rest. Find the vector of the total displacement, and its final resting position on the stick.

The Model

We model the ladybug’s motion as a one-dimensional vector problem along the length of the measuring stick.

We define the direction toward the floor as the positive direction, represented by the unit vector \(\hat{u}\), the direction toward the wall as the negative direction, \(-\hat{u}\).

Each crawl segment is represented as a displacement vector of the form

\(\vec{D}_i = (\text{magnitude}) (\pm \hat{u}).\) The total displacement is the vector sum of all individual displacement vectors.

The Math

The five displacement vectors are

The total displacement vector is

Conclusion

The ladybug’s total displacement vector is

The negative sign indicates that the net displacement is toward the wall. Because the ladybug started at the 100-cm mark, its final position is

Thus, the ladybug comes to rest at the 68-cm mark on the measuring stick.

The Verification

The code below stores the displacements in an array, computes their sum, and visualizes the motion tip-to-tail along a single axis.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Displacements in cm (positive = toward floor)

D = np.array([15, -56, 3, 25, -19])

# Starting position (cm)

x0 = 100

positions = np.concatenate([[x0], x0 + np.cumsum(D)]) # Cumulative positions

y_offsets = np.linspace(0, 4, len(D)) # Vertical offsets for visual separation

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(10, 3))

# Draw each displacement as a separate arrow

for i, (dx, y) in enumerate(zip(D, y_offsets)):

ax.arrow(positions[i], y, dx, 0, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.18, head_length=2, linewidth=3, color='tab:blue')

ax.plot(positions[i], y, 'ko', ms=6)

# Draw the resultant vector

ax.arrow(100, 4.5, D.sum(), 0, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.18, head_length=2, linewidth=3, color='tab:red')

ax.plot(100, 4.5, 'ko', ms=6)

# Label the Floor and Wall

ax.text(196, 1.8, 'Floor', ha='center', rotation=90,fontsize=11,fontweight='bold')

ax.text(4, 1.8, 'Wall', ha='center', rotation=90,fontsize=11,fontweight='bold')

# Formatting

ax.set_xlim(0, 200)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5, 5)

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xticks(np.arange(0,210,10))

ax.set_xlabel('Position along stick (cm)')

ax.set_title('Ladybug Displacement Vectors')

ax.grid(True, axis='x', alpha=0.3)

plt.show()

print(f"The total displacement is {D.sum()} cm, " f"so the final position is {x0 + D.sum()} cm.")

The total displacement is -32 cm, so the final position is 68 cm.

2.1.6. Algebra of Vectors in 2D#

Vectors can be oriented in any direction (i.e., not just parallel or antiparallel). This complicates their addition, where you cannot simply add their magnitudes to determine the resultant vector. Instead, we must use geometry to construct the resultant vector and trigonometry to find vector magnitudes and directions.

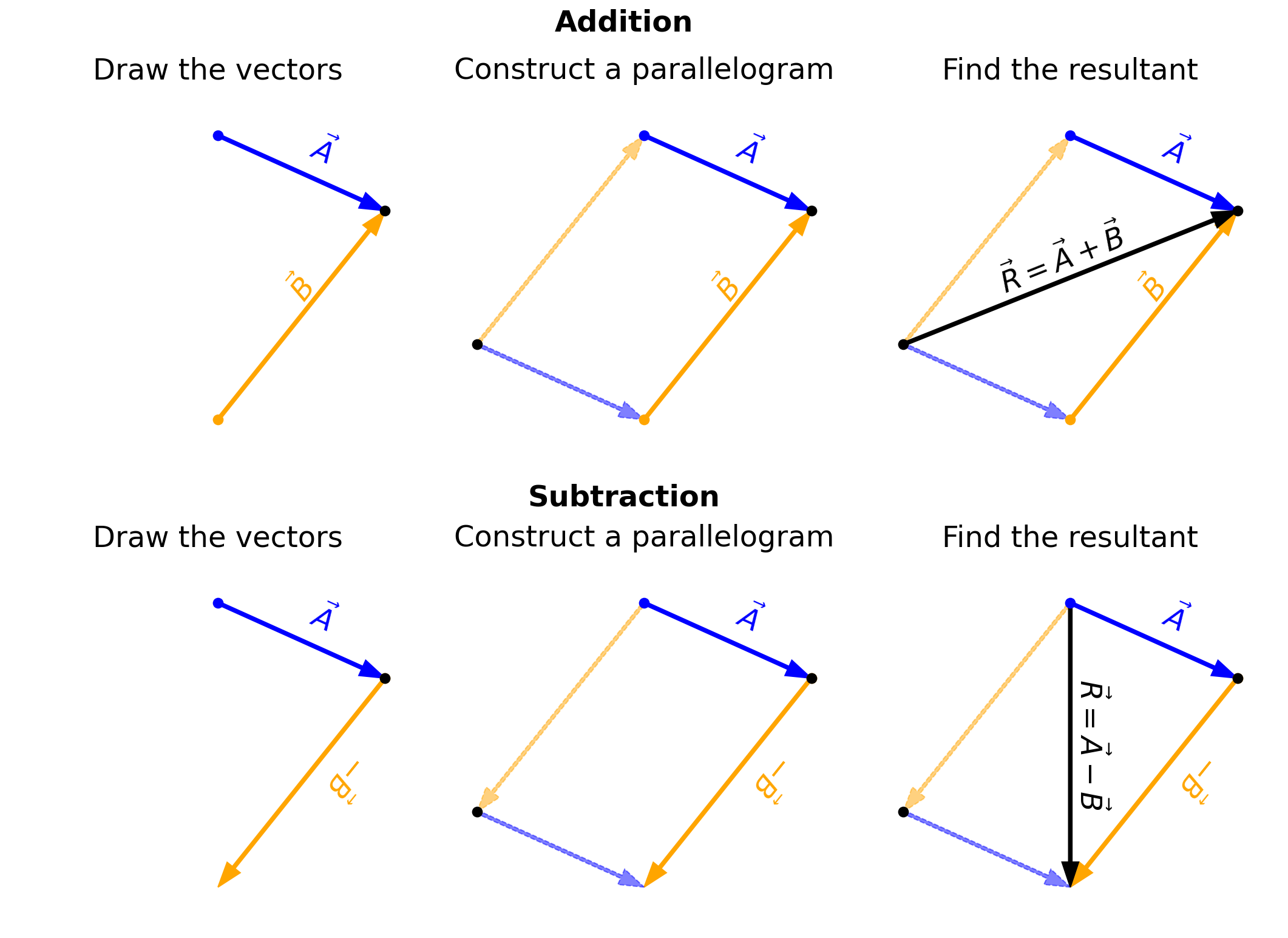

For a geometric construction of the sum of two vectors in a plane (i.e., 2D), we follow the parallelogram rule. In the figure below, it shows two ways to construct a vector graphically.

Fig. 2.7 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

To add two vectors (\(\vec{A} + \vec{B}\) ), we construct a parallelogram by shifting each vector to a parallel copy so that we can trace a path from the origin to the opposite corner of the parallelogram. The subtraction of two vectors (\(\vec{A}-\vec{B}\)) is performed in a similar way as shown in the figure below. However, notice a key difference:

in our example of vector addition, we had to move at least one vector so we could use the tail-to-head geometric construction.

in our example of vector subtraction, the resultant vector connects the blue dots, not the black dots (i.e., the other cross-piece of the parallelogram).

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import rcParams

rcParams.update({'font.size': 16})

def label_vector(ax, x0, y0, dx, dy, text, color, fontsize, offset=0.10, center=False):

xm, ym = x0 + dx/2, y0 + dy/2

nx, ny = -dy, dx

n = (nx**2 + ny**2)**0.5

nx, ny = nx/n, ny/n

angle = np.degrees(np.arctan2(dy, dx))

if center:

ax.text(xm + offset*nx, ym + offset*ny,text, color=color, fontsize=fontsize,rotation=angle, ha='center', va='center')

else:

ax.text(xm + offset*nx, ym + offset*ny, text, color=color, fontsize=fontsize, rotation=angle)

return

fs = 'x-large'

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(18,12), dpi=150)

ax1 = fig.add_subplot(231)

ax2 = fig.add_subplot(232)

ax3 = fig.add_subplot(233)

ax4 = fig.add_subplot(234)

ax5 = fig.add_subplot(235)

ax6 = fig.add_subplot(236)

ax_list_add = [ax1,ax2,ax3]

ax_list_sub = [ax4,ax5,ax6]

Ax, Ay = 1.0, -0.45

Bx, By = 1.0, 1.25

aw, hw = 0.02, 0.1

panel_titles = ["Draw the vectors","Construct a parallelogram","Find the resultant"]

for row,(ax_list,op,rowlab) in enumerate([(ax_list_add,'add',"Addition"),(ax_list_sub,'sub',"Subtraction")]):

xA0, yA0 = 0.0, 0.5

xMeet, yMeet = xA0+Ax, yA0+Ay

if op == 'add':

xB0, yB0 = xMeet-Bx, yMeet-By

xQ, yQ = xB0-Ax, yB0-Ay

pts = np.array([[xA0,yA0],[xB0,yB0],[xMeet,yMeet],[xQ,yQ]])

xmin,xmax = pts[:,0].min(), pts[:,0].max()

ymin,ymax = pts[:,1].min(), pts[:,1].max()

dxm,dym = 0.25,0.25

else:

Bx_s, By_s = -Bx, -By

xB0, yB0 = xMeet, yMeet

xEnd, yEnd = xB0+Bx_s, yB0+By_s

pts = np.array([[xA0,yA0],[xMeet,yMeet],[xEnd,yEnd],[xA0+Bx_s,yA0+By_s]])

xmin,xmax = pts[:,0].min(), pts[:,0].max()

ymin,ymax = pts[:,1].min(), pts[:,1].max()

dxm,dym = 0.25,0.25

for i,ax in enumerate(ax_list):

ax.arrow(xA0,yA0,Ax,Ay,color='b', ls='-', width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

label_vector(ax,xA0,yA0,Ax,Ay,r'$\vec{A}$','b',fs,offset=0.06)

ax.plot(xA0,yA0,'b.',ms=15)

if op == 'add':

ax.arrow(xB0,yB0,Bx,By,color='orange', ls='-', width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

label_vector(ax,xB0,yB0,Bx,By,r'$\vec{B}$','orange',fs,offset=0.14)

ax.plot(xB0,yB0,'.',color='orange',ms=15)

ax.plot(xMeet,yMeet,'k.',ms=15)

if i > 0:

ax.arrow(xQ,yQ,Ax,Ay,color='b', ls='--', alpha=0.5, width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

ax.arrow(xQ,yQ,Bx,By,color='orange', ls='--', alpha=0.5, width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

ax.plot(xQ,yQ,'k.',ms=15)

if i == 2:

Rx, Ry = xMeet-xQ, yMeet-yQ

ax.arrow(xQ,yQ,Rx,Ry,color='k', ls='-', width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

label_vector(ax, xQ, yQ, Rx, Ry,r'$\vec{R}=\vec{A}+\vec{B}$','k', fs, offset=0.12, center=True)

else:

ax.arrow(xB0,yB0,Bx_s,By_s,color='orange', ls='-', width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

label_vector(ax,xB0,yB0,Bx_s,By_s,r'$-\vec{B}$','orange',fs,offset=0.14)

ax.plot(xB0,yB0,'.',color='orange',ms=15)

ax.plot(xMeet,yMeet,'k.',ms=15)

if i > 0:

ax.arrow(xA0,yA0,Bx_s,By_s,color='orange', ls='--', alpha=0.5, width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

ax.arrow(xA0+Bx_s,yA0+By_s,Ax,Ay,color='b', ls='--', alpha=0.5, width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

ax.plot(xA0+Bx_s,yA0+By_s,'k.',ms=15)

if i == 2:

Rx, Ry = xEnd-xA0, yEnd-yA0

ax.arrow(xA0,yA0,Rx,Ry,color='k', ls='-', width=aw, length_includes_head=True, head_width=hw)

label_vector(ax, xA0, yA0, Rx, Ry,r'$\vec{R}=\vec{A}-\vec{B}$','k', fs, offset=0.12, center=True)

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.set_xlim(xmin-dxm,xmax+dxm)

ax.set_ylim(ymin-dym,ymax+dym)

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xlabel('')

ax.set_ylabel('')

ax.set_title(panel_titles[i], fontsize=fs, pad=12)

for spine in ax.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

fig.text(0.5,0.955,"Addition",ha='center',va='top',fontsize=fs,fontweight='bold')

fig.text(0.5,0.495,"Subtraction",ha='center',va='bottom',fontsize=fs,fontweight='bold')

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.02, hspace=0.25)

plt.show()

The method of tail-to-head geometric construction can be generalized to combined multiple vectors together. Consider that we have four vectors \(\vec{A},\ \vec{B},\ \vec{C},\ \text{and } \vec{D}\) as shown below.

Fig. 2.8 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

We can select any one of the vectors to start with because vector addition is commutative and associative, where the resultant \(\vec{R} = \vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C} + \vec{D}\).

Starting with \(\vec{D}\), we make a parallel translation of a

second vector \(\vec{A}\) to a position where its “tail” (i.e., origin) coincides with the “head” (i.e., end) of the first vector \(\vec{D}\).

third vector \(\vec{C}\) to a position where its origin coincides with the end of the second vector \(\vec{A}\).

fourth vector \(\vec{B}\) to a position where its origin coincides with the end of the third vector \(\vec{C}\).

We draw the resultant vector \(\vec{R}\) by connecting the “tail” of the first vector \(\vec{D}\) to the “head” of the last vector \(\vec{B}\).

2.1.6.1. Example Problem: Geometric Construction of the Resultant#

Exercise 2.2

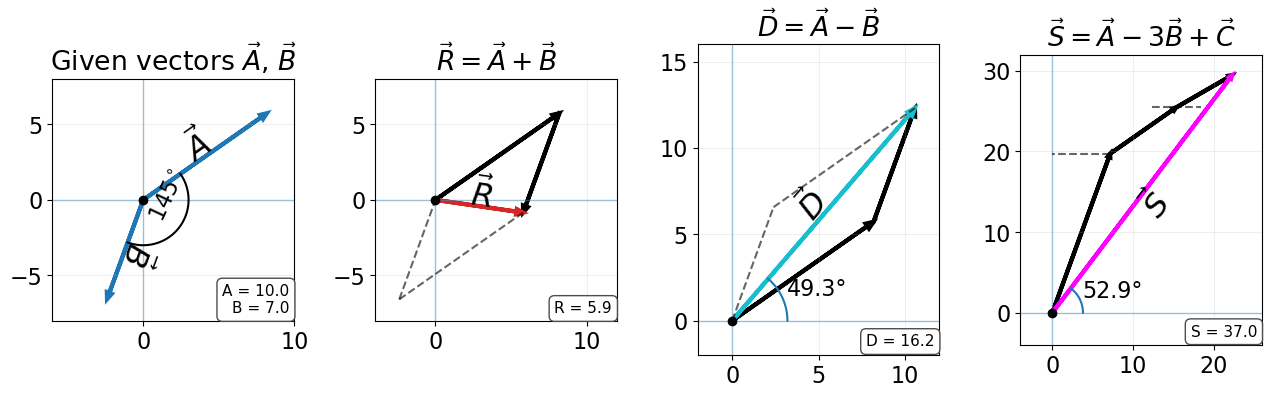

The Problem

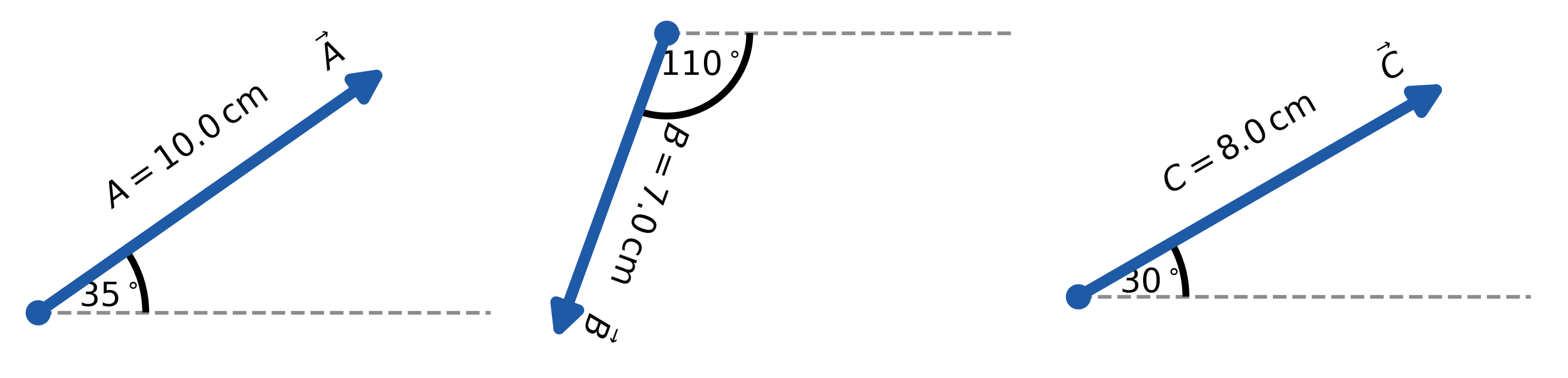

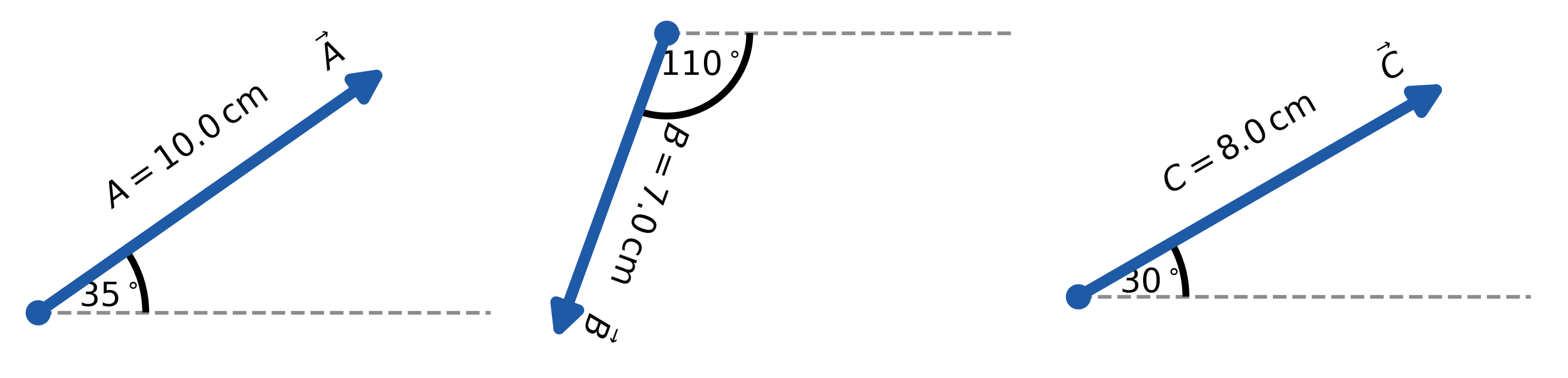

The three displacement vectors \(\vec{A}\), \(\vec{B}\), and \(\vec{C}\) lie in the horizontal plane.

Their magnitudes are \(A = 10.0\ \text{cm}\), \(B = 7.0\ \text{cm}\), and \(C = 8.0\ \text{cm}\), respectively,

and their direction angles (measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis) are

\(\alpha = 35^\circ\), \(\beta = -110^\circ\), and \(\gamma = 30^\circ\).Choose a convenient scale and use a ruler and a protractor to find the following vector sums:

(a) \(\vec{R} = \vec{A} + \vec{B}\)

(b) \(\vec{D} = \vec{A} - \vec{B}\)

(c) \(\vec{S} = \vec{A} - 3\vec{B} + \vec{C}\)

Fig. 2.9 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

The Model

Each displacement is modeled as a two-dimensional vector specified by a magnitude and a direction angle measured from the positive \(x\)-axis.

Geometric vector addition is performed by drawing vectors to scale using either:

the parallelogram rule for sums and differences of two vectors, or

the tail-to-head method for combinations involving multiple vectors or scalar multiples.

The resultant vector is drawn from the tail of the first vector to the head of the final vector.

The Math

The vector sums are determined using geometric vector addition.

Each displacement vector is drawn to scale at its specified direction angle, measured counterclockwise from the positive (x)-axis. Vectors are then combined using standard graphical techniques.

For vector addition, vectors are placed tail-to-head, and the resultant vector is drawn from the tail of the first vector to the head of the last vector.

For vector subtraction, the vector being subtracted is first reversed in direction, and the subtraction is treated as vector addition.

Using these methods:

(a) The resultant vector (\(\vec{R} = \vec{A} + \vec{B}\)) is obtained by connecting the tail of \(\vec{A}\) to the head of \(\vec{B}\). From the geometric construction,

(b) The vector (\(\vec{D} = \vec{A} - \vec{B}\)) is found by adding \(\vec{A}\) to the negative of \vec{B}. From the construction,

(c) The vector (\(\vec{S} = \vec{A} - 3\vec{B} + \vec{C}\)) is found by scaling $\vec{B}, reversing its direction, and adding all vectors sequentially. From the geometric construction,

The magnitude and direction of each resultant vector are measured directly from the scaled diagram using a ruler and protractor.

Conclusion

Geometric construction allows vector sums and differences to be determined visually when vectors are specified by magnitude and direction.

The parallelogram rule is effective for adding or subtracting two vectors.

The tail-to-head method is preferred for more complicated expressions.

While the order of addition does not change the result, drawing vectors accurately to scale is essential.

The Verification

The geometric results can be verified computationally by converting each vector into Cartesian components and evaluating the vector sums numerically.

Show code cell content

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# -----------------------

# Vector setup

# -----------------------

A_mag, B_mag, C_mag = 10.0, 7.0, 8.0

alpha_deg, phi_deg, gamma_deg = 35.0, 145.0, 30.0

A = A_mag * np.array([np.cos(np.deg2rad(alpha_deg)),

np.sin(np.deg2rad(alpha_deg))])

B = B_mag * np.array([np.cos(np.deg2rad(alpha_deg - phi_deg)),

np.sin(np.deg2rad(alpha_deg - phi_deg))])

C = C_mag * np.array([np.cos(np.deg2rad(gamma_deg)),

np.sin(np.deg2rad(gamma_deg))])

R = A + B

D = A - B

S = A - 3*B + C

# -----------------------

# Helpers

# -----------------------

def draw_arrow(ax, origin, v, **kw):

ax.arrow(*origin, *v, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.35, head_length=0.45, linewidth=3, **kw)

def info_box(ax, lines, loc="lower right"):

locs = {

"upper left": (0.02, 0.98, "left", "top"),

"upper right": (0.98, 0.98, "right", "top"),

"lower left": (0.02, 0.02, "left", "bottom"),

"lower right": (0.98, 0.02, "right", "bottom"),

}

x, y, ha, va = locs[loc]

ax.text(x, y, "\n".join(lines), transform=ax.transAxes, ha=ha, va=va, fontsize=11,

bbox=dict(boxstyle="round,pad=0.35", facecolor="white", edgecolor="0.3"))

def setup_axes(ax):

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.axhline(0, lw=1, alpha=0.4)

ax.axvline(0, lw=1, alpha=0.4)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.2)

ax.plot(0, 0, "ko", ms=6)

def label_vector(ax, x0, y0, dx, dy, text, color, fontsize, offset=0.10, center=False):

xm, ym = x0 + dx/2, y0 + dy/2

nx, ny = -dy, dx

n = (nx**2 + ny**2)**0.5

nx, ny = nx/n, ny/n

angle = np.degrees(np.arctan2(dy, dx))

if center:

ax.text(xm + offset*nx, ym + offset*ny,text, color=color, fontsize=fontsize,rotation=angle, ha='center', va='center')

else:

ax.text(xm + offset*nx, ym + offset*ny, text, color=color, fontsize=fontsize, rotation=angle)

return

# -----------------------

# Panel draw functions

# -----------------------

def panel_given(ax):

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), A, color="tab:blue")

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), B, color="tab:blue")

label_vector(ax,0,0,A[0],A[1], r"$\vec A$",'k',fs,0.8,True)

label_vector(ax,0,0,B[0],B[1], r"$\vec B$",'k',fs,0.8,True)

# included angle

t = np.linspace(np.deg2rad(alpha_deg), np.deg2rad(alpha_deg - phi_deg), 80)

r = 3

ax.plot(r*np.cos(t), r*np.sin(t),'k')

ax.text(0.7*r*np.cos(t[len(t)//2]), 0.7*r*np.sin(t[len(t)//2]), "$145^\circ$",rotation=65,horizontalalignment='center')

info_box(ax, ["A = 10.0", "B = 7.0"])

ax.set_xlim(-6, 10)

ax.set_ylim(-8, 8)

def panel_sum(ax):

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), A, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, A, B, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), R, color="tab:red")

ax.plot([B[0], R[0]], [B[1], R[1]], "k--", alpha=0.6)

ax.plot([B[0], 0], [B[1], 0], "k--", alpha=0.6)

label_vector(ax,0,0,R[0],R[1], r"$\vec R$",'k',fs,0.8,True)

info_box(ax, [f"R = {np.linalg.norm(R):.1f}"])

ax.set_xlim(-4, 12)

ax.set_ylim(-8, 8)

def panel_diff(ax):

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), A, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, A, -B, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), D, color="tab:cyan")

ax.plot([-B[0], D[0]], [-B[1], D[1]], "k--", alpha=0.6)

ax.plot([0, -B[0]], [0, -B[1]], "k--", alpha=0.6)

theta = np.arctan2(D[1], D[0])

t = np.linspace(0, theta, 80)

r = 3.2

ax.plot(r*np.cos(t), r*np.sin(t))

ax.text(1.1*r*np.cos(theta/2), 1.1*r*np.sin(theta/2), f"{np.degrees(theta):.1f}°")

label_vector(ax,0,0,D[0],D[1], r"$\vec D$",'k',fs,0.8,True)

info_box(ax, [f"D = {np.linalg.norm(D):.1f}"])

ax.set_xlim(-2, 12)

ax.set_ylim(-2, 16)

def panel_S(ax):

# Head-to-tail: -3B then A then C

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), -3*B, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, -3*B, A, color="k")

draw_arrow(ax, -3*B + A, C, color="k")

# Resultant S = A - 3B + C

draw_arrow(ax, (0,0), S, color="magenta")

# Construction guides (optional, light)

ax.plot([-3*B[0], 0], [-3*B[1], -3*B[1]], "k--", alpha=0.6)

ax.plot([0.8*(-3*B + A)[0],1.2*(-3*B + A)[0]], [(-3*B + A)[1], (-3*B + A)[1]], "k--", alpha=0.6)

# Angle marker for S

theta = np.arctan2(S[1], S[0])

t = np.linspace(0, theta, 80)

r = 3.8

ax.plot(r*np.cos(t), r*np.sin(t))

ax.text(1.1*r*np.cos(theta/2), 1.1*r*np.sin(theta/2), f"{np.degrees(theta):.1f}°")

# Optional vector symbol labels (kept minimal)

label_vector(ax,0,0,S[0],S[1], r"$\vec S$",'k',fs,-2.2,True)

# Boxed magnitude label

info_box(ax, [f"S = {np.linalg.norm(S):.1f}"])

ax.set_xlim(-4, 26)

ax.set_ylim(-4, 32)

# -----------------------

# Loop over panels

# -----------------------

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 4, figsize=(13, 4))

panels = [("Given vectors "+r"$\vec{A}$, $\vec{B}$", panel_given),

(r"$\vec R=\vec A+\vec B$", panel_sum),

(r"$\vec D=\vec A-\vec B$", panel_diff),

(r"$\vec S=\vec A-3\vec B+\vec C$", panel_S),]

for ax, (title, draw_fn) in zip(axes, panels):

setup_axes(ax)

ax.set_title(title)

draw_fn(ax)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

2.2. Coordinate Systems and Vector Components#

The graphic method of vector addition can be time-consuming, where we can instead describe a vector in terms its components within a coordinate system. In a rectangular (Cartesian) \(xy\)-coordinate system in a plane, a point is described by a pair of coordinates \((x,\ y)\) that “locate” the point. Note we used this on the chessboard using letters and numbers for each cell.

2.2.1. Vector components#

A vector \(\vec{A}\) can be decomposed into its vector components, where each component is itself a vector. These vector components are constructed using the unit vectors \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\) that mark a unit step in either the \(x\) or \(y\)-axis, respectively. Therefore, the vector \(\vec{A}\) can be represented as

where the \(A_x\) and \(A_y\) represent the magnitude of the step along the respective Cartesian axis. Recall the chessboard where the start of the vector can be anywhere on the board. This means that the component magnitudes are measurements relative to where you start.

Let’s define the starting location of vector \(\vec{A}\) as a point \((x_o,\ y_o)\), and the vector terminates at a point \((x,\ y)\). Then, we can describe the vector as

Note

When referring to \(x_o\), it is read as “x-naught”. The word naught is more commonly used in British English referring to the number zero so that one can delineate between the number zero and the letter o.

2.2.1.1. Example Problem: Mouse pointer displacement#

Exercise 2.3

The Problem

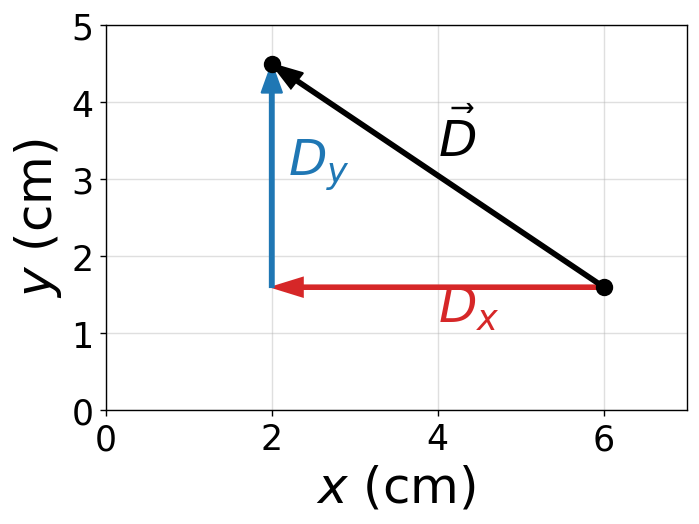

A mouse pointer on the display monitor of a computer at its initial position is at point \((6.0\ \text{cm},\,1.6\ \text{cm})\) with respect to the lower left-side corner. If you move the pointer to an icon located at point \((2.0\ \text{cm},\,4.5\ \text{cm})\), what is the displacement vector of the pointer?

The Model

We model the screen as a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system with the origin at the lower left corner of the monitor. The positive \(x\)-direction points to the right, and the positive \(y\)-direction points upward.

The displacement vector \(\vec{D}\) is defined as the vector pointing from the initial position of the pointer to its final position. Its components are obtained by subtracting the initial coordinates from the final coordinates.

The Math

Let the initial and final points point be

The components of the displacement vector are

Therefore, the displacement vector in unit-vector form is

Conclusion

The mouse pointer is displaced 4.0 cm to the left and 2.9 cm upward from its initial position. The displacement vector points into the second quadrant, reflecting a negative \(x\)-component and a positive \(y\)-component.

The Verification

We verify the displacement visually by drawing the component vectors and the resultant displacement vector using Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs = 'x-large'

# Initial and final positions (cm)

xi, yi = 6.0, 1.6

xf, yf = 2.0, 4.5

# Displacement components

Dx = xf - xi

Dy = yf - yi

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4),dpi=125)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True, zorder=2, alpha=0.4)

# x-component

ax.arrow(xi, yi, Dx, 0, color='tab:red', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=4)

ax.text(xi + Dx/2, yi - 0.4, r'$D_x$', fontsize=fs, color='tab:red')

# y-component

ax.arrow(xi + Dx, yi, 0, Dy, color='tab:blue', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=4)

ax.text(xi + Dx + 0.2, yi + Dy/2, r'$D_y$', fontsize=fs, color='tab:blue')

# resultant displacement

ax.arrow(xi, yi, Dx, Dy, color='k', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=5)

ax.text(xi + Dx/2, yi + Dy/2 + 0.2, r'$\vec{D}$', fontsize=fs)

# points

ax.plot(xi, yi, 'ko', ms=8)

ax.plot(xf, yf, 'ko', ms=8)

ax.set_xlim(0, 7)

ax.set_ylim(0, 5)

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (cm)', fontsize=fs)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (cm)', fontsize=fs)

ax.minorticks_on()

plt.show()

print(f"The displacement vector is D = ({Dx:.1f} î + {Dy:.1f} ĵ) cm.")

The displacement vector is D = (-4.0 î + 2.9 ĵ) cm.

2.2.2. Determining vector magnitude and direction#

The vector magnitude in 2D is also described as the Euclidean distance and occasionally called the Pythagorean distance. The distance along the vector \(\vec{A}\) is determined by summing the squares along the components to get \(A^2\) and taking the square root to get the magnitude \(A\).

The square root permits positive and negative results, where we take the absolute magnitude. The direction will be resolve by the direction angle \(\theta_A\).

Fig. 2.10 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

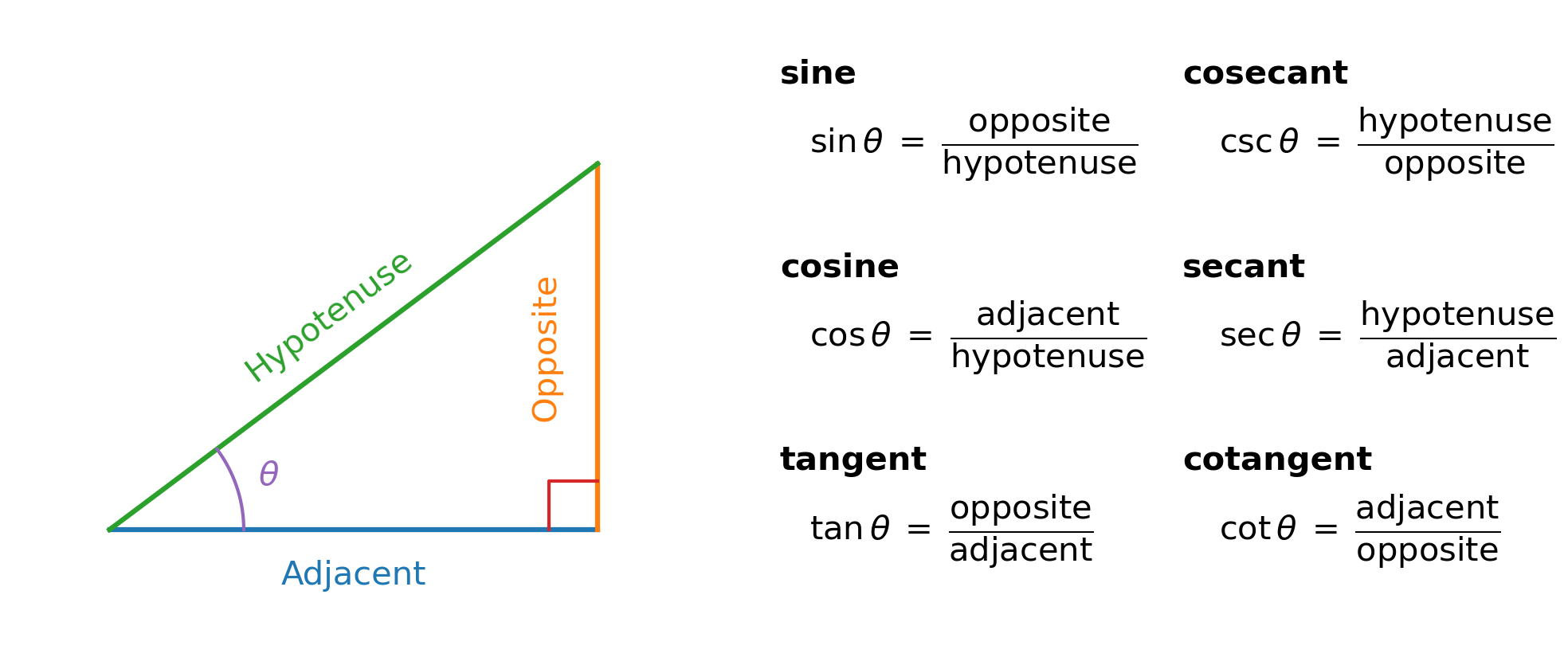

From the Euclidean distance formula (or Pythagorean theorem), we have

This equation works even when the components (\(A_x,\ A_y\)) are negative. The direction angle of a vector is determined using a trigonometric function. See the triangle below and the summary of the trig functions. Various mnemonics are used to help remember these relations (e.g., SOH-CAH-TOA).

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib import rcParams

rcParams.update({'font.size': 20})

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(14,6), dpi=150)

axL = fig.add_subplot(121)

axR = fig.add_subplot(122)

# -------------------------

# LEFT: Right triangle

# -------------------------

A = np.array([0.0, 0.0])

B = np.array([4.0, 0.0])

C = np.array([4.0, 3.0])

c_adj = '#1f77b4' # blue

c_opp = '#ff7f0e' # orange

c_hyp = '#2ca02c' # green

c_theta = '#9467bd' # purple

c_right = '#d62728' # red

axL.plot([A[0], B[0]], [A[1], B[1]], lw=3, color=c_adj)

axL.plot([B[0], C[0]], [B[1], C[1]], lw=3, color=c_opp)

axL.plot([A[0], C[0]], [A[1], C[1]], lw=3, color=c_hyp)

s = 0.4

axL.plot([B[0]-s, B[0]-s, B[0]], [B[1], B[1]+s, B[1]+s], lw=2, color=c_right)

def unit(v):

n = (v[0]**2 + v[1]**2)**0.5

return v/n

def label_side(ax, P, Q, text, color, offset=0.30, rotate=True):

mid = 0.5*(P+Q)

v = Q-P

u = unit(v)

n = np.array([-u[1], u[0]])

ang = np.degrees(np.arctan2(v[1], v[0]))

ax.text(mid[0]+offset*n[0], mid[1]+offset*n[1], text,

color=color, rotation=ang if rotate else 0,

ha='center', va='center')

# Tighten Adjacent/Opposite offsets

label_side(axL, A, B, "Adjacent", c_adj, offset=-0.38, rotate=False)

label_side(axL, B, C, "Opposite", c_opp, offset=0.42, rotate=True)

label_side(axL, A, C, "Hypotenuse", c_hyp, offset=0.32, rotate=True)

# Theta arc at A: more room

theta = np.arctan2(C[1]-A[1], C[0]-A[0])

r = 1.10

t = np.linspace(0, theta, 140)

axL.plot(A[0] + r*np.cos(t), A[1] + r*np.sin(t), lw=2, color=c_theta)

axL.text(A[0] + 1.25*r*np.cos(theta/2),

A[1] + 1.25*r*np.sin(theta/2),

r'$\theta$', color=c_theta, ha='center', va='center')

axL.set_aspect('equal')

axL.set_xlim(-0.8, 5.2)

axL.set_ylim(-1.0, 4.2)

axL.set_xticks([])

axL.set_yticks([])

for spine in axL.spines.values():

spine.set_visible(False)

# -------------------------

# RIGHT: Trig definitions (aligned grid)

# -------------------------

axR.axis('off')

# Column anchors

x_name_L = 0.0

x_eq_L = 0.04

x_name_R = 0.55

x_eq_R = 0.6

# Row anchors

y1, y2, y3 = 0.78, 0.48, 0.18

dy_title = 0.11

# Left column

axR.text(x_name_L, y1+dy_title, "sine", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_L, y1, r'$\sin\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{opposite}}{\mathrm{hypotenuse}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_name_L, y2+dy_title, "cosine", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_L, y2, r'$\cos\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{adjacent}}{\mathrm{hypotenuse}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_name_L, y3+dy_title, "tangent", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_L, y3, r'$\tan\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{opposite}}{\mathrm{adjacent}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

# Right column

axR.text(x_name_R, y1+dy_title, "cosecant", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_R, y1, r'$\csc\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{hypotenuse}}{\mathrm{opposite}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_name_R, y2+dy_title, "secant", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_R, y2, r'$\sec\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{hypotenuse}}{\mathrm{adjacent}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_name_R, y3+dy_title, "cotangent", fontweight='bold', transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

axR.text(x_eq_R, y3, r'$\cot\theta \;=\; \dfrac{\mathrm{adjacent}}{\mathrm{opposite}}$',

transform=axR.transAxes, ha='left')

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Since we have the lengths of both the adjacent (\(A_x\)) and opposite (\(A_y\)) sides of the triangle, it is easiest to use the \(\tan{\theta}\) function, which results in

If \(\vec{A}\) lies in quadrants I or IV, the angle \(\theta = \theta_A\), but it is measured in the

counterclockwise direction in quadrant I,

clockwise direction (negative) in quadrant IV

relative to the \(x\)-axis.

To find \(\theta_A\) in quadrants II or III, one must use the relation \(\theta_A = 180^\circ + \theta\) because \(\theta<0\) due to \(A_y/A_x < 0\).

Fig. 2.11 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

2.2.2.1. Example Problem: Mouse pointer magnitude and direction#

Exercise 2.4

The Problem

You move a mouse pointer on the display monitor from its initial position at point \((6.0\ \text{cm},\, 1.6\ \text{cm})\) to an icon located at point \((2.0\ \text{cm},\, 4.5\ \text{cm})\). What are the magnitude and direction of the displacement vector of the pointer?

The Model

We model the screen as a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system with the origin at the lower left corner of the monitor. The positive \(x\)-direction points to the right, and the positive \(y\)-direction points upward.

The displacement vector \(\vec{D}\) points from the initial position to the final position. Its components are found by subtraction:

The Math

Let the initial and final points be

The displacement components are

Magnitude

Direction

First compute the reference angle using the ratio of components:

Because \(D_x<0\) and \(D_y>0\), the vector lies in Quadrant II. Therefore the direction angle measured counterclockwise from \(+x\) is

Common Mistake

A very common mistake when finding the direction of a displacement vector is to compute

and stop there.

This inverse tangent only returns angles between \(-90^\circ\) and \(+90^\circ\). It does not know which quadrant the vector lies in.

What can go wrong

If \(D_x < 0\), the vector is in Quadrant II or III.

If \(D_y < 0\), the vector is in Quadrant III or IV.

The raw \(\tan^{-1}\) value must often be adjusted by \(180^\circ\).

In this problem:

so the displacement vector lies in Quadrant II, not Quadrant IV. Failing to account for this would give the wrong direction angle.

Best practice

Always check the signs of \(D_x\) and \(D_y\).

Or, when using Python, use

np.arctan2(Dy, Dx), which automatically returns the correct quadrant.

Conclusion

The displacement vector has magnitude \(D = 4.9\ \text{cm}\) and direction \(\theta_D = 144.1^\circ\) (counterclockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis). It points into Quadrant II, consistent with \(D_x=-4.0\ \text{cm}\) and \(D_y=+2.9\ \text{cm}\).

The Verification

We verify the components, magnitude, and direction visually by drawing \(\vec{D}\) and its component vectors using Python.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

fs = 'x-large'

# Given points (cm)

xi, yi = 6.0, 1.6

xf, yf = 2.0, 4.5

# Components

Dx, Dy = xf - xi, yf - yi

# Magnitude and direction (CCW from +x)

D = np.hypot(Dx, Dy)

theta = np.degrees(np.arctan2(Dy, Dx)) # already quadrant-correct

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4), dpi=125)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True, zorder=2, alpha=0.4)

# Component arrows (single-line arrow calls)

ax.arrow(xi, yi, Dx, 0, color='tab:red', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=4)

ax.arrow(xi + Dx, yi, 0, Dy, color='tab:blue', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=4)

# Resultant displacement arrow

ax.arrow(xi, yi, Dx, Dy, color='k', ls='-', width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.25, zorder=5)

# Points

ax.plot(xi, yi, 'k.', ms=18, zorder=6)

ax.plot(xf, yf, 'k.', ms=18, zorder=6)

# Labels

ax.text(xi + Dx/2, yi - 0.45, r'$D_x$', fontsize=fs, color='tab:red')

ax.text(xi + Dx + 0.20, yi + Dy/2, r'$D_y$', fontsize=fs, color='tab:blue')

ax.text(xi + Dx/2, yi + Dy/2 + 0.25, r'$\vec{D}$', fontsize=fs, color='k')

ax.set_xlim(0, 7)

ax.set_ylim(0, 5)

ax.set_xlabel('$x$ (cm)', fontsize=fs)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$ (cm)', fontsize=fs)

plt.show()

print(f"The displacement has magnitude D = {D:.1f} cm and direction θ = {theta:.1f}° (CCW from +x).")

The displacement has magnitude D = 4.9 cm and direction θ = 144.1° (CCW from +x).

2.2.3. Polar coordinates#

To locate a point on a plane, we need two orthogonal directions. In the Cartesian coordinate system, we used the unit vectors \(\hat{i}\) and \(\hat{j}\). When considering rotating objects, it can be easier working in the polar coordinate system.

The location of a point is instead defined by the radial coordinate \(r\) (i.e., distance from the origin) and angular coordinate \(\varphi\) (sometimes called the azimuthal coordinate) which measures the rotation angle with some chosen direction, usually the positive \(x\)-direction. The angular coordinate is often measured in radians.

The unit vectors for polar coordinates are given as \(\hat{r}\) (radial) and \(\hat{t}\) (transverse). The \(\hat{r}\) describes points outward in radius relative to the center. The positive \(\hat{t}\) direction indicates how the angle \(\varphi\) changes in the counterclockwise direction.

We can connect a the Cartesian point to a polar equivalent via a transformation:

See the figure below, which shows the relationsip between Cartesian and polar coordinates.

Fig. 2.12 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

2.2.3.1. Example Problem: Coins near a well#

Exercise 2.5

The Problem

A treasure hunter finds one silver coin at a location \(20.0\) m away from a dry well in the direction \(20^\circ\) north of east and finds one gold coin at a location \(10.0\) m away from the well in the direction \(20^\circ\) north of west. What are the polar and rectangular coordinates of these findings with respect to the well?

The Model

We treat the dry well as the origin of a two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system. By convention, the positive \(x\)-axis points east and the positive \(y\)-axis points north. With this choice, any location in the plane can be described either by its distance and direction from the origin (polar coordinates) or by its horizontal and vertical displacements (rectangular coordinates).

Each coin is naturally described in polar form because its distance from the well and its direction are given directly. To compare the locations using standard vector components, we convert these polar descriptions into rectangular coordinates using the relations

All angles are measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis.

The Math

For the silver coin, the given description places it \(20.0\) m from the well at an angle of \(20^\circ\) north of east. In polar form, this corresponds to

Substituting these values into the coordinate relations gives

The gold coin is located \(20^\circ\) north of west. Because west corresponds to \(180^\circ\) measured from the positive \(x\)-axis, the direction angle for this coin is

Using the same coordinate relations,

The Conclusion

The silver coin is located at \((x_S, y_S) = (18.9\ \text{m},\ 6.8\ \text{m}),\) placing it east and north of the well. The gold coin is located at \((x_G, y_G) = (-9.4\ \text{m},\ 3.4\ \text{m}),\) which places it west and north of the well.

The signs of the \(x\)-components correctly encode the physical directions: positive for eastward displacement and negative for westward displacement, while both coins have positive \(y\)-components because they lie north of the well.

The Verification

We can confirm these coordinate conversions numerically by evaluating the trigonometric expressions directly using Python, which also helps reinforce the connection between the mathematical model and a computational implementation.

import numpy as np

# Angles in radians

theta_s = np.pi/9

theta_g = 8*np.pi/9

# Radii

r_s = 20.0

r_g = 10.0

# Cartesian coordinates

x_s, y_s = r_s*np.cos(theta_s), r_s*np.sin(theta_s)

x_g, y_g = r_g*np.cos(theta_g), r_g*np.sin(theta_g)

print(f"Silver coin: (x, y) = ({x_s:.1f}, {y_s:.1f}) m")

print(f"Gold coin: (x, y) = ({x_g:.1f}, {y_g:.1f}) m")

Silver coin: (x, y) = (18.8, 6.8) m

Gold coin: (x, y) = (-9.4, 3.4) m

2.2.4. Vectors in 3D#

To specify a location in space (in general), we need three coordinates (\(x,\ y,\ z\)), where two coordinates (\(x,\ y\)) can identify points in a plane, and the \(z\)-coordinate locates points that extend above or below the plane. The advent of an extra coordinate necessitates the inclusion of a third unit vector \(\hat{k}\).

The order of the coordinates \(x-y-z\) and the unit vectors \(\hat{i}-\hat{j}-\hat{k}\) defines the standard right-handed coordinate system. In this coordinate system, “up” is now defined using the \(+\hat{z}\) direction and aligns with your right thumb. That means the positive azimuthal (polar) angle uses the \(x\)-axis as a reference direction and rotates counterclockwise (from \(\hat{i}\) to \(\hat{j}\)), which follows the curve of your fingers as you curl them. The figure below illustrates the unit vectors and how they map to the edges of a cube in 3D space.

Fig. 2.13 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

The 3D version of the vector \(\vec{A}\) has three components, which can be represented by the sum of the components by

The magnitude \(A\) is now defined by generalizing the distance equation to

The figure below illustrates the vector components and how they map to the edges of a cube in 3D space.

Fig. 2.14 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

2.2.4.1. Example Problem: Takeoff of a drone#

Exercise 2.6

The Problem

During a takeoff of an IAI Heron drone, its position with respect to a control tower is \(100\) m above the ground, \(300\) m to the east, and \(200\) m to the north. One minute later, its position is \(250\) m above the ground, \(1200\) m to the east, and \(2100\) m to the north. What is the drone’s displacement vector with respect to the control tower? What is the magnitude of this displacement vector?

The Model

We model space using a three-dimensional Cartesian coordinate system:

\(+x\) points east

\(+y\) points north

\(+z\) points upward

The displacement vector \(\vec{D}\) points from the initial position to the final position, and its components are found by subtracting coordinates:

The Math

The drone’s displacement vector is defined by the change in its position between two instants in time. At takeoff, the drone is located at the point \((x_i, y_i, z_i) = (300,\ 200,\ 100)\ \text{m},\) measured relative to the control tower. One minute later, its position is \((x_f, y_f, z_f) = (1200,\ 2100,\ 250)\ \text{m}.\)

The components of the displacement vector are obtained by subtracting the initial coordinates from the final coordinates along each axis. This givesi

Then, the displacement vector can be written in unit-vector form as

Expressing the components in kilometers gives \(\vec{D} = (0.90\hat{i} + 1.90\hat{j} + 0.15\hat{k})\ \text{km}.\)

The magnitude of the displacement depends only on the lengths of its components, not on their directions. Using the three-dimensional magnitude formula,

The Conclusion

The drone’s displacement vector is \( \vec{D} = (0.90\hat{i} + 1.90\hat{j} + 0.15\hat{k})\ \text{km},\) with a magnitude of 2.11 km. This result reflects a dominant horizontal displacement toward the northeast with a smaller vertical climb.

The Verification

We verify the displacement calculation numerically using Python.

import numpy as np

r_i = np.array([300, 200, 100])

r_f = np.array([1200, 2100, 250])

D = r_f - r_i

D_mag = np.linalg.norm(D)/1000 # km

print(f"Displacement vector (m): {D}")

print(f"Magnitude of displacement: {D_mag:.2f} km")

2.3. Algebra of Vectors#

We’ve seen some properties of vectors from Section 2.1.5 Properties of Vectors, where there a few other properties not yet mentioned. A vector can be

reversed (i.e., multiplied by a scalar, \(-1\)),

nullified,

made equal.

To reverse the direction of a vector, we follow the rules for scaling a vector:

The number zero can be generalized to vector algebra through the object called the null vector, denoted by \(\vec{0}\). It represents a vector that has no length or direction,

If the difference of two vectors (\(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\)) is set to the null vector, we have

By matching components, we can see that

When \(\vec{A}-\vec{B} = \vec{0}\), this implies that \(\vec{A} = \vec{B}\) because all their corresponding components are equal.

2.3.1. Example Problem: Military convoy direction#

Exercise 2.7

The Problem

A military convoy advances through unknown territory. In a Cartesian coordinate system, the unit vector \(\hat{i}\) denotes geographic east, \(\hat{j}\) denotes geographic north, and \(\hat{k}\) denotes altitude above sea level. The convoy’s velocity is given by

\[ \vec{v} = (4.0\hat{i} + 3.0\hat{j} + 0.1\hat{k}) \ \text{km/h}.\]If the convoy were forced to retreat, in what geographic direction would it be moving? Describe both its horizontal direction and its vertical motion.

The Model

We model the convoy’s motion using a 3-dimensional velocity vector expressed in Cartesian components. The horizontal motion occurs in the east–north plane, while the vertical motion is represented by the \(\hat{k}\) component.

A retreat corresponds to reversing the direction of motion. Therefore, the retreat velocity vector must be antiparallel to the original velocity vector. This means the new velocity vector points in the opposite direction but retains the same relative component ratios.

The Math

The original velocity vector is

The vertical component \(+0.1\hat{k}\) indicates the convoy is ascending at a rate of \(0.1\) km/h (or \(100\) m/h). The horizontal components show motion toward the northeast.

The direction of the horizontal motion is determined by

To retreat, the velocity must reverse direction. We write the retreat velocity as

where \(\alpha\) is a positive constant. Thus,

The negative \(\hat{k}\) component indicates the convoy would be descending during the retreat.

The horizontal direction of the retreat is given by

Conclusion: The convoy retreats at an angle of \(37^\circ\) south of west while descending.

The Verification

We can verify the direction numerically using Python by storing the velocity components in an array and computing the angle directly.

import numpy as np

# Original velocity components (km/h)

v = np.array([4.0, 3.0, 0.1])

# Retreat velocity (antiparallel)

u = -v

# Horizontal direction angle

theta = np.degrees(np.arctan(abs(u[1] / u[0])))

print("Retreat velocity vector:", u)

print("Horizontal direction angle:", np.round(theta,1), "degrees")

Retreat velocity vector: [-4. -3. -0.1]

Horizontal direction angle: 36.9 degrees

2.3.2. Analytical vector addition#

Resolving vectors into their scalar components allows us to use vector algebra to find sums and differences of vectors without using graphical methods (i.e., analytically). For example, to find the resultant of two vectors \(\vec{A}\) and \(\vec{B}\), we simply add them relative to their components.

Component Matching Rule

Vectors can only be added or subtracted by combining matching components.

\(\hat{i}\) components combine only with \(\hat{i}\)

\(\hat{j}\) components combine only with \(\hat{j}\)

\(\hat{k}\) components combine only with \(\hat{k}\)

For example,

but expressions like

cannot be simplified further because none of the subscripts match.

If the subscripts do not match, the components represent different directions and cannot be combined.

Vector addition by components is accomplished as follows:

Analytical methods can be used to find the result of many vectors by combining them by components. For example, if we sum up \(N\) vectors (\(\vec{F}_1,\ldots,\vec{F}_N\)), where each vector \(\vec{F}_n = F_{nx}\hat{i} + F_{ny}\hat{j} + F_{nz}\hat{k}\), the resultant vector is

The resultant vector is defined as:

where

Show code cell content

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.patches import Arc

import matplotlib as mpl

from myst_nb import glue

mpl.rcParams.update({

"figure.dpi": 300,

"savefig.dpi": 300,

"font.size": 12,

"mathtext.fontset": "dejavusans",

"font.family": "DejaVu Sans",

"axes.titlesize": 18,

"axes.labelsize": 14,

})

def label_on_vector(ax, x0, y0, dx, dy, text, fontsize=18, offset=0.12, frac=0.55,

color="k", weight=None, rotate_with_vector=True):

xm, ym = x0 + frac*dx, y0 + frac*dy

nx, ny = -dy, dx

n = (nx**2 + ny**2)**0.5

nx, ny = (0.0, 0.0) if n == 0 else (nx/n, ny/n)

ang = np.degrees(np.arctan2(dy, dx))

rot = ang if rotate_with_vector else 0.0

ax.text(xm + offset*nx, ym + offset*ny, text,

rotation=rot, rotation_mode="anchor",

ha="center", va="center",

fontsize=fontsize, color=color, fontweight=weight, clip_on=False)

def draw_vector_panel(ax, mag, ang_deg, name, units="cm", vec_color="#1f5aa6"):

th = np.deg2rad(ang_deg)

vx, vy = mag*np.cos(th), mag*np.sin(th)

ax.set_aspect("equal", adjustable="box")

ax.set_xticks([]); ax.set_yticks([])

for s in ax.spines.values(): s.set_visible(False)

ax.plot([0, 1.05*mag], [0, 0], ls="--", lw=1.6, color="0.55", zorder=1)

ax.annotate("", xy=(vx, vy), xytext=(0, 0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="-|>", lw=5, color=vec_color, mutation_scale=26),

zorder=4)

ax.plot(0, 0, "o", ms=10, color=vec_color, zorder=5)

arc_r = 0.50*mag

if ang_deg >= 0:

t1, t2 = 0, ang_deg

mid = np.deg2rad(0.5*ang_deg)

ang_label = rf"${ang_deg:.0f}^\circ$"

else:

t1, t2 = ang_deg, 0

mid = np.deg2rad(0.5*ang_deg)

ang_label = rf"${abs(ang_deg):.0f}^\circ$"

ax.add_patch(Arc((0, 0), arc_r, arc_r, theta1=t1, theta2=t2,

lw=3.0, color="k", zorder=3))

ax.text(0.34*arc_r*np.cos(mid), 0.24*arc_r*np.sin(mid), ang_label,

fontsize=fs, ha="center", va="center", clip_on=False)

# vector symbol (on the vector)

label_on_vector(ax, 0, 0, 2*vx, 2*vy, rf"${name}$", fontsize=fs, offset=0.10*mag, frac=0.45)

# --- magnitude label: centered + perpendicular offset above the vector ---

name_mag = name[5:6]

label_on_vector(ax, 0, 0, vx, vy, rf"${name_mag}={mag:.1f}\,\mathrm{{{units}}}$",

fontsize=fs, offset=0.12*mag, frac=0.50, rotate_with_vector=True)

# limits + padding (extra to avoid clipping rotated text)

xs = np.array([0, vx, 1.05*mag])

ys = np.array([0, vy, 0])

xmin, xmax = xs.min(), xs.max()

ymin, ymax = ys.min(), ys.max()

pad = 0.05*mag

ax.set_xlim(xmin-pad, xmax+pad)

ax.set_ylim(ymin-pad, ymax+pad)

fs = 'large'

A, alpha = 10.0, 35

B, beta = 7.0, -110

C, gamma = 8.0, 30

fig, axes = plt.subplots(1, 3, figsize=(12, 8), dpi=300)

draw_vector_panel(axes[0], A, alpha, r"\vec{A}")

draw_vector_panel(axes[1], B, beta, r"\vec{B}")

draw_vector_panel(axes[2], C, gamma, r"\vec{C}")

plt.subplots_adjust(wspace=0.05)

glue("vec_ABC", fig, display=False)

fig.savefig("vectors.png", bbox_inches="tight", pad_inches=0.05)

plt.show()

2.3.2.1. Example Problem: Vector addition component-wise#

Exercise 2.8

The Problem

Three displacement vectors \(\vec{A}\), \(\vec{B}\), and \(\vec{C}\) lie in the horizontal plane. Their magnitudes are \(A = 10.0\ \text{cm}\), \(B = 7.0\ \text{cm}\), and \(C = 8.0\ \text{cm}\), and their direction angles (measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis) are \(\alpha = 35^\circ\), \(\beta = -110^\circ\), and \(\gamma = 30^\circ\), respectively.

Resolve each vector into its Cartesian components and determine the following:

(a) \(\vec{R} = \vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}\)

(b) \(\vec{D} = \vec{A} - \vec{B}\)

(c) \(\vec{S} = \vec{A} - 3\vec{B} + \vec{C}\)

The Model

We model each displacement vector using Cartesian components in the \(x\)–\(y\) plane. Each vector is resolved into horizontal (\(\hat{i}\)) and vertical (\(\hat{j}\)) components using trigonometry. Vector addition and subtraction are then carried out component-by-component.

Once the components of each resultant vector are known, the vector can be written in unit-vector form.

The Math

Each displacement vector is first resolved into Cartesian components using trigonometry.

For a vector of magnitude (V) making an angle (\theta) with the positive \(x\)-axis, the components are

Applying this to vectors (\(\vec{A}\), \(\vec{B}\), and \(\vec{C}\)) yields their respective \(x\)- and \(y\)-components. Vector addition and subtraction are then performed component by component.

The components of \(\vec{A}\) are

The components of \(\vec{B}\) are

The components of \(\vec{C}\) are

Once the components of a resultant vector are known, the vector is written in unit-vector form. Its magnitude is found using the Pythagorean theorem, \(|\vec{R}| = \sqrt{R_x^2 + R_y^2},\) and its direction angle is determined from \(\theta = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{R_y}{R_x}\right)\), with the appropriate quadrant correction applied.

(a) Resultant \(\vec{R} = \vec{A} + \vec{B} + \vec{C}\)

Thus,

(b) Difference \(\vec{D} = \vec{A} - \vec{B}\)

Thus,

(c) Combination \(\vec{S} = \vec{A} - 3\vec{B} + \vec{C}\)

Thus,

Conclusion

By resolving vectors into Cartesian components, vector addition and subtraction reduce to straightforward algebra. The analytical method provides exact results and avoids the geometric uncertainties inherent in graphical techniques.

The Verification

We can verify these results numerically by storing each vector as a NumPy array and performing the same component-wise operations.

import numpy as np

A = np.array([8.19, 5.73])

B = np.array([-2.39, -6.58])

C = np.array([6.93, 4.00])

R = A + B + C

D = A - B

S = A - 3*B + C

print("R =", R, "cm")

print("D =", D, "cm")

print("S =", S, "cm")

R = [12.73 3.15] cm

D = [10.58 12.31] cm

S = [22.29 29.47] cm

2.3.2.2. Example Problem: Tug-of-war game with Dug#

Exercise 2.9

The Problem

Four dogs named Astro, Balto, Clifford, and Dug play a tug-of-war game with a toy. We define east as the positive \(x\)-direction and north as the positive \(y\)-direction.

Astro pulls with a force of magnitude \(A = 160.0,\text{N}\) at an angle \(\alpha = 55^\circ\) south of east. Balto pulls with a force of magnitude \(B = 200.0,\text{N}\) at an angle \(\beta = 60^\circ\) east of north. Clifford pulls with a force of magnitude \(C = 140.0,\text{N}\) at an angle \(\gamma = 55^\circ\) west of north.

Dug pulls on the toy in such a way that the toy does not move.

What force must Dug apply (magnitude and direction) in order to keep the toy in equilibrium?

Fig. 2.15 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

The Model

Each dog’s pull is modeled as a force vector in the \(x\)–\(y\) plane. The toy remains at rest only if the vector sum of all forces acting on it is zero.

We first compute the resultant force of Astro, Balto, and Clifford:

For equilibrium, Dug’s force \(\vec{D}\) must cancel this resultant. Therefore, Dug’s pull must be antiparallel to \(\vec{R}\):

The Math

We begin by converting all direction descriptions into standard angles measured counterclockwise from the positive \(x\)-axis:

Astro: \(\theta_A = -55^\circ\)

Balto: \(\theta_B = 90^\circ - 60^\circ = 30^\circ\)

Clifford: \(\theta_C = 90^\circ + 55^\circ = 145^\circ\)

Next, we resolve each force into components:

Numerically, this gives:

Now we compute the components of the resultant force:

Thus, the resultant force is

Dug’s force must be equal in magnitude and opposite in direction:

The magnitude of Dug’s force is

The direction angle is

Because both components of \(\vec{D}\) are negative, the direction is south of west.

Conclusion

To keep the toy in equilibrium, Dug must pull with a force of magnitude \(158.1 \text{N}\) directed \(18.1^\circ\) south of west.

Verification (Python)

The short Python script below computes the vector sum of the three dogs’ forces and confirms that Dug’s force is equal in magnitude and opposite in direction.

import numpy as np

A = 160*np.array([np.cos(np.radians(-55)), np.sin(np.radians(-55))])

B = 200*np.array([np.cos(np.radians(30)), np.sin(np.radians(30))])

C = 140*np.array([np.cos(np.radians(145)), np.sin(np.radians(145))])

R = A + B + C

D = -R

D_mag = np.linalg.norm(D)

D_ang = np.degrees(np.arctan2(D[1], D[0])) + 180

print("Dug must pull with a force of magnitude: %4.1f N directed %2.1f south of west." % (D_mag,D_ang))

Dug must pull with a force of magnitude: 158.2 N directed 18.1 south of west.

2.3.2.3. Example Problem: 3D vector magnitude#

Exercise 2.10

The Problem

Find the magnitude of the vector \(\vec{C}\) that satisfies the vector equation

\[ 2\vec{A} - 6\vec{B} + 3\vec{C} = 2\hat{j},\]where the known vectors are

\[ \vec{A} = \hat{i} - 2\hat{k}, \qquad \vec{B} = -\hat{j} + \frac{1}{2}\hat{k}.\]

The Model

This is a three-dimensional vector equation written in the \(\hat{i}\), \(\hat{j}\), and \(\hat{k}\) basis. We solve algebraically for the unknown vector \(\vec{C}\), identify its Cartesian components, and then compute its magnitude using the standard Euclidean norm.

The Math

We begin by isolating \(\vec{C}\):