3. Motion along 1D#

3.1. Position, Displacement, and Average Velocity#

3.1.1. Position#

To describe the motion of an object, must first locate it using its position \(x\) (i.e., where it is at any particular time.). More precisely, we need to specify its position relative to a convenient frame of reference.

A frame of reference is an arbitrary set of axes from which the position (and motion) of an object are described. We often describe the position of an object relative to the “stationary” Earth or objects on the Earth. For example,

a rocket could relate its position relative to the Earth as a whole,

a cyclist’s position could relate to the nearby buildings.

It is not necessary for the reference to be stationary. For example, to describe a position of a person in an airplane, we use the airplane as the reference frame even though it is moving through the air.

Typically, we use the variable \(x\) when discussing 1-D motion (in general), where we might use the variable \(y\) when discussing vertical motion.

3.1.2. Displacement#

If an object moves relative to a frame of reference, then the object’s position changes (i.e., displacement). The word displacement implies that an object has moved. Recall from Chapter 2, displacement is a vector with magnitude and direction. In 1-D, the direction is simply represented as a positive (\(+\)) or negative (\(-\)) relative to the reference. For example,

moving \(2\ {\rm m}\) to the right is indicated by a displacement of \(+2\ {\rm m}\),

moving \(4\ {\rm m}\) to the left is indicated by a displacement of \(-4\ {\rm m}\).

Displacement \(\Delta x\) is the change in position of an object:

where \(x_f\) is the final position and \(x_o\) is the initial position.

Note

We use the uppercase Greek letter delta (\(\Delta\)) to mean “change in” a variable. Thus, \(\Delta x\) means change in position. We always solve for displacement with the difference of \(x_o\) from \(x_f\).

Objects in motion can have a series of displacements, where we define total displacement \(\Delta x_{Tot}\) as the sum of the individual displacements (recall how we summed multiple vectors to find the resultant), and express this mathematically as,

where \(\Delta x_i\) are the individual displacements. In the earlier example, we had \(\Delta x_1 = 2\ {\rm m}\) and \(\Delta x_2 = -4\ {\rm m}\) so that \(\Delta x_{Tot} = -2\ {\rm m}\). But we need to work out the individual \(x_i\). Here’s what we know,

This means we have

What is \(x_o\)? – It’s the initial reference or where we started before moving at all (i.e., the origin). In this case, \(x_o = 0\), which means we now know

\(\boxed{x_o = 0}\)

\(x_1 - 0 = 2\ {\rm m} \rightarrow \boxed{x_1 = 2\ {\rm m}}\).

\(x_2 - 2\ {\rm m} = -4\ {\rm m} \rightarrow \boxed{x_2 = -2\ {\rm m}}\)

Thus, the total displacement is given by

The total displacement is \(-2\ {\rm m}\) along the \(x\)-axis, or \(\vec{D} = -2\hat{i}\ {\rm m}\). The above process can be represented in vectors by

The magnitude of the displacement is always positive, \(|D| = \sqrt{\vec{D}\cdot \vec{D}}\). In this case, we can find that \(\boxed{|D| = 2\ {\rm m}}\).

The distance traveled \(d\) should not be confused with the magnitude of the total displacement. The distance traveled is the total length of the path between the two positions, where it is determined

and in this case,

3.1.3. Average Velocity#

To calculate how fast something is moving, we must introduce the time variable \(t\). Similar to the displacement \(\Delta x\), there is a time between two points, which is called the elapsed time \(\Delta t = t_f - t_o\).

If \(x_f\) and \(x_o\) are the positions of an object at times \(t_f\) and \(t_o\), respectively, then the average velocity \(\bar{v}\) is

Note

The average velocity is a vector and can be negative, when \(x_f<x_o\). This means that the average velocity can be in the opposite direction as the positive reference direction.

3.1.3.1. Example Problem: Delivering Flyers#

Exercise 3.1

The Problem

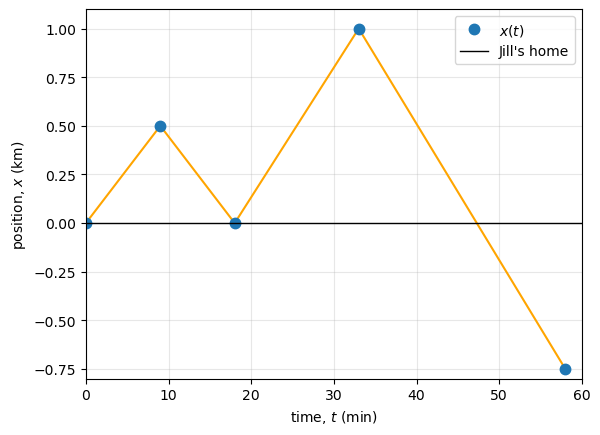

Jill sets out from her home to deliver flyers for her yard sale, traveling due east along her street lined with houses. At 0.5 km and 9 minutes later she runs out of flyers and has to retrace her steps back to her house to get more. This takes an additional 9 minutes. After picking up more flyers, she sets out again on the same path, continuing where she left off, and ends up 1.0 km from her house. This third leg of her trip takes 15 minutes. At this point she turns back toward her house, heading west. After 1.75 km and 25 minutes she stops to rest.

a. What is Jill’s total displacement to the point where she stops to rest?

b. What is the magnitude of the final displacement?

c. What is the average velocity during her entire trip?

d. What is the total distance traveled?

e. Make a graph of position versus time.

The Model

We model Jill’s motion as one-dimensional along an east–west line. We choose:

\(+x\) = east

\(-x\) = west

Jill’s home is the origin: \(x_o = 0\)

The wording gives us the position and time at the end of each leg, so the clean way to organize the information is a table of \((t_i, x_i)\) and the corresponding segment displacements \(\Delta x_i = x_i - x_{i-1}\).

The Math

We begin by assigning a coordinate system. Jill’s motion takes place along a straight east–west line, so we treat it as one-dimensional. We choose east to be the positive \(x\)-direction and take Jill’s home as the origin, \(x_o=0\). The problem statement provides Jill’s position and elapsed time at the end of each leg of her trip, which allows us to reconstruct her motion step by step.

Jill starts from rest at her home, so at \(t_o=0\ \text{min}\) her position is \(x_o=0\ \text{km}\). After traveling east for 9 minutes, she is 0.5 km from her house, giving \(t_1=9\ \text{min}\) and \(x_1=+0.5\ \text{km}\). She then retraces her steps back to her house, which takes an additional 9 minutes, so at \(t_2=18\ \text{min}\) her position is again \(x_2=0\).

After picking up more flyers, Jill sets out once more along the same path and continues past her previous turnaround point. This third leg lasts 15 minutes and leaves her 1.0 km from home, so \(t_3=33\ \text{min}\) and \(x_3=+1.0\ \text{km}\). Finally, she turns around and heads west for 25 minutes, covering 1.75 km in the negative direction. At the moment she stops to rest, the elapsed time is \(t_4=58\ \text{min}\) and her position is

From these positions we can compute the displacement during each leg of the trip using \(\Delta x_i = x_i - x_{i-1}\):

(a) Total displacement is the net change in position from the start of the trip to the stopping point. Because displacement depends only on initial and final positions, we have

(b) Magnitude of the final displacement is the absolute value of this result:

(c) Average velocity over the entire trip is defined as total displacement divided by total elapsed time. The total time is 58 minutes, so

(d) Total distance traveled differs from displacement because Jill reverses direction. The distance is the sum of the magnitudes of each segment displacement:

The Conclusion

Jill’s final displacement is \(\boxed{-0.75\ \text{km}}\), meaning she ends \(\boxed{0.75\ \text{km}}\) west of her house.

The average velocity is negative, \(\boxed{\bar{v}\approx -0.013\ \text{km/min}}\), because her net motion over the whole trip is toward the west.

The total distance traveled is \(\boxed{3.75\ \text{km}}\), which is larger than the displacement because she reverses direction multiple times.

The Verification

We can verify the arithmetic and generate the position–time graph using Python. The graph is piecewise linear because we only know Jill’s position at the end of each leg.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# --- Data from the problem (time in min, position in km) ---

t = np.array([0, 9, 18, 33, 58])

x = np.array([0, 0.5, 0, 1.0, -0.75])

# Segment displacements and totals

dx = np.diff(x) #np.diff finds \Delta x

dt_total = t[-1] - t[0]

dx_total = x[-1] - x[0]

distance_total = np.sum(np.abs(dx))

v_avg = dx_total / dt_total

print(f"Total displacement: {dx_total:.2f} km")

print(f"Magnitude of displacement: {abs(dx_total):.2f} km")

print(f"Average velocity: {v_avg:.4f} km/min")

print(f"Total distance traveled: {distance_total:.2f} km")

# --- Plot position vs time ---

fig = plt.figure()

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(t, x, "-",color='orange')

ax.plot(t, x, '.', ms=15,label=r"$x(t)$")

ax.set_xlabel(r"time, $t$ (min)")

ax.set_ylabel(r"position, $x$ (km)")

ax.axhline(0, linewidth=1,color='k',label="Jill's home") # home reference line

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Tight limits to remove excess whitespace

ax.set_xlim(0,60)

ax.set_ylim(-0.8, 1.1)

plt.show()

Total displacement: -0.75 km

Magnitude of displacement: 0.75 km

Average velocity: -0.0129 km/min

Total distance traveled: 3.75 km

3.2. Instantaneous Velocity and Speed#

3.2.1. Instantaneous Velocity#

The quantity that tells us how fast an object is moving anywhere along its path is the instantaneous velocity, or simply velocity. It is the average velocity between two discrete points on the path.

Suppose we know the position \(x\) of an object at any time \(t\), then we would know the continuous function \(x(t)\). We can express the average velocity \(\bar{v}\) by

To find the instantaneous velocity at any position, we let \(t_1 \rightarrow t\) and \(t_2 \rightarrow t + \Delta t\). Then we substitute into our expression for the average velocity and define \(v(t)\) by,

We now define the instantaneous velocity of an object is the limit of the average velocity \(\bar{v}\) as the elapsed time \(\Delta t\) approaches zero, or the derivative of \(x\) with respect to \(t\):

Instantaneous velocity is a vector with dimension of \(L/T\). Since the definition of average velocity is written in terms of the change in position \(\Delta x\) over a specific time interval \(\Delta t\), we also refer to the velocity as the rate of change of the position function.

The rate of change is a measure of how fast a function is changing at a time \(t\), or the slope of the line that is tangent to the curve at \(t\). The displacement at the initial time \(t_o\) is zero (i.e., \(\Delta x = 0\)), therefore the velocity will also be zero and the slope will be flat.

At other times (\(t_1,\ t_2,\dots,\ t_N\)), the velocity is not zero (unless the position never changes) because the slope would be positive or negative. If the function \(x(t)\) had a minimum, then the slope would also be zero (i.e., \(v(t) = 0\)). Thus, the zeros of the velocity function give the minimum and maximum of the position function.

Fig. 3.1 Image Credit: Openstax.#

3.2.1.1. Example Problem: Plotting velocity from position#

Exercise 3.2

The Problem

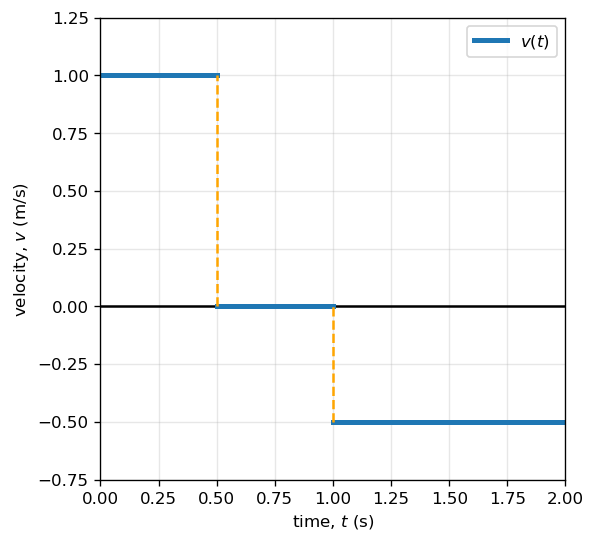

A position–versus–time graph is shown in Fig. 3.2. Using this graph, determine the corresponding velocity–versus–time graph.

Specifically:

Identify the velocity during each time interval.

Sketch or describe the resulting velocity–time graph.

Fig. 3.2 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The Model

We model the motion as one-dimensional motion along a straight line, with position \(x\) measured along a single axis. The position–time graph consists of straight-line segments, which means the velocity is constant within each time interval.

In one dimension, the velocity over a time interval is given by the slope of the position–time graph:

Thus, the velocity during each interval can be found by computing the slope of the corresponding line segment on the graph. Changes in slope correspond to changes in velocity.

The Math

The position–time graph is piecewise linear, with three distinct time intervals.

From \(t=0\) to \(t=0.5\ \text{s}\), the position increases from \(x=0.0\ \text{m}\) to \(x=0.5\ \text{m}\). The velocity during this interval is

From \(t=0.5\) to \(t=1.0\ \text{s}\), the position remains constant at \(x=0.5\ \text{m}\). Because there is no change in position, the velocity is

From \(t=1.0\) to \(t=2.0\ \text{s}\), the position decreases from \(x=0.5\ \text{m}\) to \(x=0.0\ \text{m}\). The velocity during this interval is

These constant velocities define a piecewise-constant velocity–time graph.

The Conclusion

The velocity is positive during the first interval, zero during the second interval when the object is momentarily at rest, and negative during the final interval when the object reverses direction and moves back toward the origin.

The velocity–time graph therefore consists of three horizontal segments:

\(v = +1.0\ \text{m/s}\) from \(0\) to \(0.5\ \text{s}\),

\(v = 0\) from \(0.5\) to \(1.0\ \text{s}\),

\(v = -0.5\ \text{m/s}\) from \(1.0\) to \(2.0\ \text{s}\).

This confirms that the slope of the position–time graph at any time gives the object’s instantaneous velocity.

The Verification

We can reproduce the velocity–time graph using Python by encoding the velocities as a piecewise function. This numerical construction reproduces the velocity–time graph implied by the slopes of the original position–time graph.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Time intervals (s)

t = np.array([0.0, 0.5, 1.0, 2.0])

# Corresponding velocities (m/s)

v = np.array([1.0, 0.0, -0.5])

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,5),dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.axhline(0, linewidth=1.5, color='k')

# Plot piecewise-constant velocity

ax.plot([0,0.5],[1,1],'-',color='tab:blue',lw=3,label=r"$v(t)$")

ax.plot([0.5,1.0],[0,0],'-',color='tab:blue',lw=3)

ax.plot([1,2],[-0.5,-0.5],'-',color='tab:blue',lw=3)

# Plot lines to connect the jumps; these are not physical

#axvline(x_o,y_o/y_range,y_f/y_range,kwargs); the y-values are scaled over the full y-range

ax.axvline(0.5,0.375,0.875,linestyle='--',color='orange',lw=1.5)

ax.axvline(1.0,0.125,0.375,linestyle='--',color='orange',lw=1.5)

ax.set_xlabel(r"time, $t$ (s)")

ax.set_ylabel(r"velocity, $v$ (m/s)")

ax.legend()

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.3)

# Tight limits

ax.set_xlim(0, 2.0)

ax.set_ylim(-0.75, 1.25)

plt.show()

3.2.2. Speed#

Most people use the terms speed and velocity interchangeably. In physics, they do not have the same meaning and are distinct concepts. Speed is a scalar, while velocity is a vector.

We calculate the average speed \(\bar{s}\) by

Average speed is different than average velocity because the numerator Total distance is always a positive quantity, and hence, average speed cannot be negative. For example, if a trip starts and ends at the same location,

the total displacement is zero, which implies the average velocity is zero.

the total distance traveled is not zero and thus, the average speed is not zero.

However, we can calculate the instantaneous speed from the magnitude of the instantaneous velocity, or

Two particles moving in opposite directions can have the same speed, but have different velocities. Table 3.1 shows some typical speeds in \(\rm m/s\) and \(\rm mph\).

Speed |

m/s |

mi/h |

|---|---|---|

Continental drift |

\(10^{-7}\) |

\(2\times10^{-7}\) |

Brisk walk |

1.7 |

3.9 |

Cyclist |

4.4 |

10 |

Sprint runner |

12.2 |

27 |

Rural speed limit |

24.6 |

56 |

Official land speed record |

341.1 |

763 |

Speed of sound at sea level |

343 |

768 |

Space shuttle on reentry |

7,800 |

17,500 |

Escape velocity of Earth\(^\ast\) |

11,200 |

25,000 |

Orbital speed of Earth around the Sun |

29,783 |

66,623 |

Speed of light in a vacuum |

299,792,458 |

670,616,629 |

\(^\ast\) Escape velocity is the speed at which an object must be launched so that it overcomes Earth’s gravity and is not pulled back toward Earth.

3.2.3. Calculating Instantaneous Velocity#

If the position function \(x(t)\) is has the form of \(at^n\), where \(A\) is a constant and \(n\) is an integer, then it can be differentiated using the power rule by,

Note

If there are additional terms added together (e.g., \(x(t) = At^n + Bt^m\)), then the power rule of differentiation is distributive, where it can be done multiple times and the solution is the sum of those terms.

If \(x(t) = A\), then the derivative is equal to zero. The slope of a constant horizontal line is zero like we saw at the maximum \(x(t_o)\) in Fig. 3.1.

3.2.3.1. Example Problem: Instantaneous Velocity vs. Average Velocity#

Exercise 3.3

The Problem

The position of a particle moving along the \(x\)-axis is given by

\[ x(t) = (3.0\ \text{m/s})\,t + (0.5\ \text{m/s}^3)\,t^3.\]a. Using the definition of instantaneous velocity, find the instantaneous velocity at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\).

b. Calculate the average velocity between \(t = 1.0\ \text{s}\) and \(t = 3.0\ \text{s}\).

The Model

Velocity describes how position changes with time.

The instantaneous velocity is the derivative of position with respect to time:

\[ v(t) = \frac{dx}{dt}. \]The average velocity over a time interval is the change in position divided by the elapsed time:

\[ \bar{v} = \frac{x(t_2)-x(t_1)}{t_2-t_1}. \]

Because \(x(t)\) is a polynomial in \(t\), we can differentiate it directly and evaluate it at the required time. For the average velocity, we evaluate \(x(t)\) at the two endpoints and compute the slope between those points.

The Math

To find the instantaneous velocity, we differentiate the position function term-by-term. Since

its derivative is

Evaluating at \(t=2.0\ \text{s}\) gives

To find the average velocity from \(t_1=1.0\ \text{s}\) to \(t_2=3.0\ \text{s}\), we first compute the positions at the endpoints:

The change in position is \(\Delta x = 22.5-3.5 = 19.0\ \text{m}\) and the elapsed time is \(\Delta t = 3.0-1.0 = 2.0\ \text{s}\), so

The Conclusion

The instantaneous velocity at \(t=2.0\ \text{s}\) is \(\boxed{9.0\ \text{m/s}}\), while the average velocity from \(1.0\ \text{s}\) to \(3.0\ \text{s}\) is \(\boxed{9.5\ \text{m/s}}\).

These values are not identical because the particle’s velocity is increasing with time due to the \(t^3\) term in \(x(t)\). Over the interval from 1 s to 3 s, the object spends more time moving faster than it was earlier, so the average velocity ends up slightly larger than \(v(2.0\ \text{s})\).

The Verification

The python script below evaluates and computes both the instantaneous velocity and the average velocity. It reproduces the expected results where \(\bar{v} \neq v\).

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Position and velocity functions (from the analytic work)

def x(t):

return 3.0*t + 0.5*t**3

def v(t):

return 3.0 + 1.5*t**2

# Quantities requested in the problem

v_inst = v(2.0)

v_avg = (x(3.0) - x(1.0)) / (3.0 - 1.0)

print(f"Instantaneous velocity at t = 2.0 s: v(2.0) = {v_inst:.1f} m/s")

print(f"Average velocity from t = 1.0 s to t = 3.0 s: v_avg = {v_avg:.1f} m/s")

Instantaneous velocity at t = 2.0 s: v(2.0) = 9.0 m/s

Average velocity from t = 1.0 s to t = 3.0 s: v_avg = 9.5 m/s

3.3. Average and Instantaneous Acceleration#

3.3.1. Average Acceleration#

The average acceleration \(\bar{a}\) is the rate of change for the velocity \(v\):

where \(t\) is time.

The SI units for acceleration are meters per second squared (or meters per second per second) and abbreviated as \(\rm m/s^2\). This means how much the velocity has changed every second, where the velocity can change in either magnitude or direction due to it being a vector. For example,

a runner traveling at \(10\ {\rm km/h}\) due east slows to a stop reverses direction, and continues to run \(10\ {\rm km/h}\) due west.

Before turning around, the runner had one average acceleration, then a different average acceleration afterwards. This is shown mathematically as,

The magnitude of the velocity is the same in both directions, however the direction is different. Acceleration is a vector in the same direction as the change in velocity \(\Delta v\). Acceleration is a change in speed or direction, or both.

Note

Although acceleration is in the direction of the change in velocity, it is not always in the direction of motion. When an object slows down, its acceleration is opposite to the direction of its motion.

The term deceleration can cause confusion because it is not a vector and it does not point to a specific direction with respect to a specific direction.

We can say the runner was decelerating before coming to a stop and accelerating afterward, but we shouldn’t include the coordinate system unit vector (\(\hat{i}\) or \(-\hat{i}\)) in our analysis. Otherwise the runner always has a negative acceleration, in contrast to our intuition. Instead of using the term deceleration, we describe the motion more accurately with a positive or negative acceleration relative to the coordinate system.

If an object has a velocity in the positive direction with respect to the origin and it acquires a constant negative acceleration, the object eventually comes to rest and reverses direction (i.e., our runner in \(\Delta t_1\)). Eventually, the object passes through the origin going in the opposite direction (i.e., our runner in \(\Delta t_2\)).

Fig. 3.3 An object in motion with a velocity vector toward the east under negative acceleration comes to a rest and reverses direction. It passes the origin going in the opposite direction after a long enough time. Image Credit: Openstax.#

3.3.1.1. Example Problem: Racehorse Leaves the Gate#

Exercise 3.4

The Problem

A racehorse coming out of the gate accelerates from rest to a velocity of \(15.0 {\rm m/s}\) due west in \(1.80 {\rm s}\). What is its average acceleration?

The Model

We begin by assigning a coordinate system so that directions are clearly defined. Let east be the positive direction and west be the negative direction. With this choice, any velocity or acceleration toward the west will be negative.

Fig. 3.4 Identify the coordinate system, the given information, and what you want to determine. Image Credit: Openstax.#

Average acceleration is defined as the change in velocity divided by the elapsed time,

If we identify the initial and final velocities and the time interval, we can calculate the average acceleration directly.

The Math

The horse starts from rest, so the initial velocity is \(v_o = 0.\) After \(1.80\ \text{s}\), the horse’s velocity is \(15.0\ \text{m/s}\) toward the west. Because west is defined as the negative direction, the final velocity is \(v_f = -15.0\ \text{m/s}.\)

The elapsed time is \(\Delta t = 1.80\ \text{s}.\) The change in velocity is therefore

Substituting into the definition of average acceleration gives

The Conclusion

The average acceleration of the horse is \(\boxed{\bar{a} = -8.33\ {\rm m/s^2}}.\) The negative sign indicates that the acceleration is directed toward the west, consistent with the horse increasing its speed in that direction (i.e., \(\bar{a} = (.33\ {\rm m/s^2}\ [-\hat{i}]\)).

Acceleration describes how quickly velocity changes, including its direction. An acceleration of \(8.33\ \text{m/s}^2\) toward the west means that the horse’s westward velocity increases by \(8.33\ \text{m/s}\) every second. This value represents an average acceleration, since the motion may not be perfectly smooth throughout the ride.

The Verification

We can verify this result numerically using Python by computing the change in velocity and dividing by the elapsed time. This mirrors the analytical calculation but helps reinforce the definition of average acceleration.

# Given values

v0 = 0.0 # m/s

vf = -15.0 # m/s (west is negative)

dt = 1.80 # s

# Average acceleration

a_avg = (vf - v0) / dt

print(f"Average acceleration = {a_avg:.2f} m/s^2")

3.3.2. Instantaneous Acceleration#

Instantaneous acceleration \(a\), or acceleration at a time \(t\), is found using the same process discussed for instantaneous velocity. We calculate, the average acceleration between two points in time \(\Delta t\) and let \(\Delta t \rightarrow 0\). The result is the derivative of the velocity function \(v(t)\) and is expressed as

We can show that the instantaneous acceleration at \(t_o\) is the slope of the tangent line to the velocity graph at time \(t_o\). The average acceleration approaches the instantaneous acceleration as \(\Delta t \rightarrow 0\).

Fig. 3.5 Image Credit: Openstax.#

As shown in Fig. 3.5a, the velocity has a maximum when its slope is zero, which corresponds to a zero of the acceleration function. In Fig. 3.5b, there is a minimum velocity when the acceleration is zero. The zeros of the acceleration function give either the minimum or maximum velocity.

Calculus Note: Derivatives, Extrema, and Evolution

Finding Extrema by Setting the Derivative to Zero

One of the most powerful and general uses of calculus is identifying where a quantity reaches a maximum or minimum.

Given a function \(f(x)\), extrema occur at critical points, which satisfy

(or where the derivative is undefined).

This works because the derivative represents the rate of change of the function. At a maximum or minimum, the function momentarily stops increasing or decreasing, so its slope is zero.

Examples

In kinematics, setting \(v(t) = \frac{dx}{dt} = 0\) finds when an object momentarily stops or turns around.

In optimization, setting \(\frac{dE}{dx} = 0\) finds stable equilibrium configurations.

In thermodynamics, extrema of entropy or energy determine equilibrium states.

This method applies to any differentiable function, not just position or velocity.

Using Derivatives to Evolve a System

Derivatives do more than identify special points. They describe how systems change in time. Many physical laws are written as differential equations, which specify how a quantity evolves:

Here, the derivative tells us how the system changes at each instant. Solving the differential equation allows us to predict the system’s future behavior.

Examples

Newton’s Second Law:

\[ m\frac{dv}{dt} = F(x,v,t) \]determines how velocity evolves from forces.

Radioactive decay:

\[ \frac{dN}{dt} = -\lambda N \]describes how a quantity decreases over time.

Population growth, electrical circuits, orbital motion, and climate models are all governed by differential equations.

Big Picture

Setting derivatives equal to zero finds where something stops changing (extrema, turning points, equilibrium).

Using derivatives in equations tells us how something changes (motion, growth, decay, evolution).

Together, these ideas form the mathematical backbone of physics, engineering, and applied science.

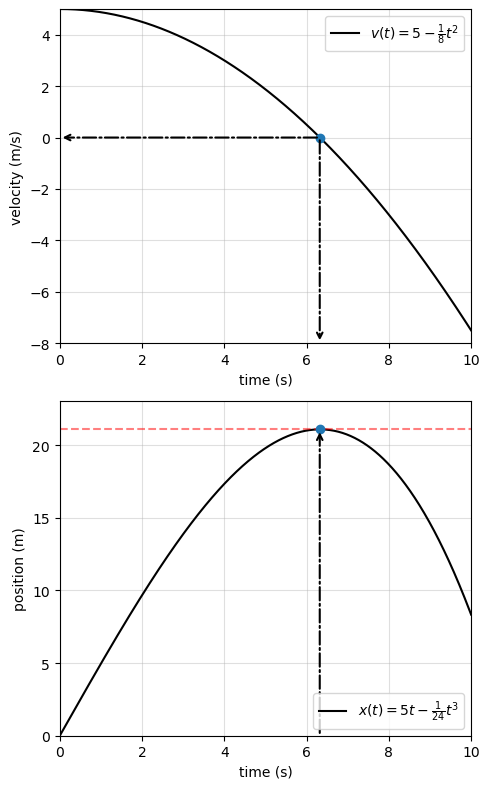

3.3.2.1. Example Problem: Calculating Instantaneous Acceleration#

Exercise 3.5

The Problem

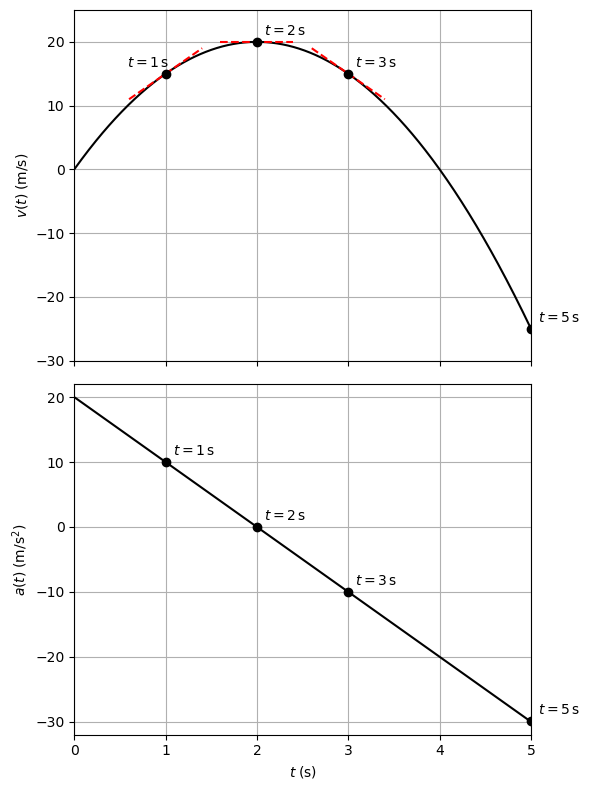

A particle is in one-dimensional motion and is accelerating. The functional form of its velocity is \(v(t) = (20\ \text{m/s}^2)t - (5\ \text{m/s}^3)t^2.\)

a. Find the functional form of the acceleration.

b. Find the instantaneous velocity at \(t = 1,\ 2,\ 3,\) and \(5\,\text{s}\).

c. Find the instantaneous acceleration at \(t = 1,\ 2,\ 3,\) and \(5\,\text{s}\).

d. Interpret the results of part (c) in terms of the directions of the acceleration and velocity vectors.

The Model

The acceleration of a particle is defined as the time derivative of its velocity. Because the velocity is given explicitly as a function of time, we can determine the acceleration function analytically by differentiating \(v(t)\).

Once we have expressions for both velocity and acceleration, we evaluate them at specific times to determine their magnitudes and signs. The signs of velocity and acceleration encode direction in one dimension and allow us to determine whether the particle is speeding up, slowing down, or reversing direction.

The Math

We begin by finding the acceleration as the derivative of the velocity function,

Taking the derivative term by term gives

(b) Instantaneous velocity

We evaluate the velocity function at the specified times:

(c) Instantaneous acceleration

Next, we evaluate the acceleration function:

(d) Interpreting the motion

At \(t=1\,\text{s}\), both velocity and acceleration are positive, so the particle is moving in the positive direction and speeding up. At \(t=2\,\text{s}\), the acceleration is zero while the velocity is positive. This corresponds to a maximum velocity, since the slope of the velocity curve is zero at that instant.

At \(t=3\,\text{s}\), the velocity is still positive but the acceleration is negative, so the particle is slowing down. At \(t=5\,\text{s}\), both velocity and acceleration are negative. The particle has reversed direction and is now speeding up in the negative direction.

The Conclusion

This example illustrates how velocity and acceleration together describe motion. The zero of the acceleration function marks the time at which the velocity reaches an extremum. When velocity and acceleration point in the same direction, the particle speeds up; when they point in opposite directions, the particle slows down. A change in the sign of the velocity indicates a reversal of direction.

The Verification

We can verify these results numerically and visually by evaluating and plotting the velocity and acceleration functions.

The printed values match the analytical results, and the plots clearly show that the velocity reaches a maximum when the acceleration crosses zero. Here we compute \(a(t)\) two ways: analytically from \(dv/dt\) and numerically using a central-difference derivative of the sampled \(v(t)\). The agreement provides an independent check.

Although the derivative is often introduced using a forward difference, a central difference gives a more accurate numerical approximation to the instantaneous rate of change because it samples symmetrically around the point of interest. The central difference of a function \(f(t)\) is given as

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Analytic functions (for comparison)

def v_analytic(t):

return 20*t - 5*t**2

def a_analytic(t):

return 20 - 10*t

# Time grid (uniform spacing is explicit)

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, 5.01, dt)

# Sample velocity from the analytic function (this is our "measured" data stream)

v = v_analytic(t)

# Central-difference acceleration from sampled velocity (independent numerical verification)

# a_i ≈ (v_{i+1} - v_{i-1}) / (2 dt)

a_num = np.empty_like(v)

a_num[1:-1] = (v[2:] - v[:-2]) / (2*dt)

# One-sided differences at endpoints (not central, but avoids NaNs at the plot edges)

a_num[0] = (v[1] - v[0]) / dt

a_num[-1] = (v[-1] - v[-2]) / dt

# Times for annotations / tangents

t_points = np.array([1, 2, 3, 5])

t_tangent = np.array([1, 2, 3])

# Helper: find nearest index on the grid

def idx_of_time(tp):

return int(np.round((tp - t[0]) / dt))

# Print comparisons at the marked times

print("Instantaneous values (analytic vs. numeric central-difference):")

for tp in t_points:

i = idx_of_time(tp)

print(

f"t = {tp:>2} s : "

f"v = {v[i]:>6.2f} m/s, "

f"a_analytic = {a_analytic(tp):>7.2f} m/s^2, "

f"a_numeric = {a_num[i]:>7.2f} m/s^2"

)

# Plot settings packed for reuse in a single loop

series = [

{"y": v,"color": "black","ylabel": r"$v(t)\;(\mathrm{m/s})$","ylim": (-30, 25),"use_tangents": True},

{"y": a_num,"color": "black","ylabel": r"$a(t)\;(\mathrm{m/s^2})$", "ylim": (-32, 22),"use_tangents": False},

]

fig, axes = plt.subplots(nrows=2, ncols=1, figsize=(6, 8), sharex=True,dpi=100)

for ax, s in zip(axes, series):

y = s["y"]

# Main curve and marked points

ax.plot(t, y, color=s["color"])

ax.scatter(t_points, [y[idx_of_time(tp)] for tp in t_points], color="black", zorder=3)

# Annotations

for tp in t_points:

i = idx_of_time(tp)

t_off = t[i]

if abs(tp - 1)<1e-4 and s["use_tangents"]:

t_off += -0.5

ax.annotate(rf"$t={tp}\,\mathrm{{s}}$",(t_off, y[i]),textcoords="offset points",xytext=(5, 5),fontsize=10)

# Tangent lines on v(t) panel: slope comes from *numeric* acceleration at that time

# (this reinforces "slope = derivative" using the numerical derivative)

if s["use_tangents"]:

half_span = 0.4

for tp in t_tangent:

i0 = idx_of_time(tp)

slope = a_num[i0] # numeric slope

t0,v0 = t[i0],y[i0]

t_local = np.arange(t0 - half_span, t0 + half_span + dt, dt)

v_tan = v0 + slope * (t_local - t0)

ax.plot(t_local, v_tan, linestyle="--", color="r", linewidth=1.5)

ax.set_ylabel(s["ylabel"])

ax.set_xlim(0, 5)

ax.set_ylim(*s["ylim"])

ax.grid(True)

axes[1].set_xlabel(r"$t\;(\mathrm{s})$")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Instantaneous values (analytic vs. numeric central-difference):

t = 1 s : v = 15.00 m/s, a_analytic = 10.00 m/s^2, a_numeric = 10.00 m/s^2

t = 2 s : v = 20.00 m/s, a_analytic = 0.00 m/s^2, a_numeric = 0.00 m/s^2

t = 3 s : v = 15.00 m/s, a_analytic = -10.00 m/s^2, a_numeric = -10.00 m/s^2

t = 5 s : v = -25.00 m/s, a_analytic = -30.00 m/s^2, a_numeric = -29.95 m/s^2

3.3.3. Getting a Feel for Accelerations#

You feel an acceleration when riding an elevator or stepping on the gas (“go”) pedal in your car. However, the sense of scale for acceleration is provided in Table 3.2. Expressing acceleration in units of \(g\) helps relate these values to everyday experience and to the forces objects must withstand.

Acceleration |

Value (m/s²) |

Value (\(g\)) |

|---|---|---|

High-speed train |

0.25 |

0.03 |

Elevator |

2 |

0.20 |

Cheetah |

5 |

0.5 |

Object in free fall without air resistance near the surface of Earth, \(g\) |

9.8 |

1 |

Space shuttle maximum during launch |

29 |

3 |

Parachutist peak during normal opening of parachute |

59 |

6 |

F16 aircraft pulling out of a dive |

79 |

8 |

Explosive seat ejection from aircraft |

147 |

15 |

Sprint missile |

982 |

100 |

Fastest rocket sled peak acceleration |

1540 |

160 |

Jumping flea |

3200 |

330 |

Baseball struck by a bat |

30,000 |

3,000 |

Closing jaws of a trap-jaw ant |

1,000,000 |

100,000 |

Proton in the Large Hadron Collider |

\(2 \times 10^{9}\) |

\(2 \times 10^{8}\) |

3.4. Motion with Constant Acceleration#

3.4.1. Notation#

To make things simpler, we introduce some conventions in notation. One simplification is taking \(t_o = 0\), which is the point in time when you begin to measure. Time exists before this point, but until “you get your Delorean to 88 mph”, then it doesn’t make sense to include the past.

The elapsed time goes from \(\Delta t = t_f - t_o\) to \(\Delta t = t_f\). We don’t need the subscript \(f\) anymore. So, the elapsed is \(\Delta t = t\). We can drop the subscript \(f\) from the \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta v\) as well. In our simplified notation we have

where the subscript \(o\) denotes an initial value and the absence of a subscript indicates the final value of the variable.

For now, we will also make the assumption that the acceleration is constant. As a result, the average and instantaneous acceleration are equal, or

In many situations in this course, the acceleration is constant. When it isn’t (e.g., a car accelerating to top speed, then braking to a stop), the motion will be considered in separate parts (lik with the runner) and each part has its own constant acceleration.

3.4.2. Displacement and Position from Velocity#

To get our first two equations, we start with the definition of average velocity:

and substitute the simplified notation to get

Solving for \(x\) gives

where the arithmetic average velocity is

This version of \(\bar{v}\) reflects that when acceleration is constant, then \(\bar{v}\) is the simple average of the initial and final velocities.

3.4.3. Solving for Final Velocity from Acceleration and Time#

We can derive another useful equation by manipulating the definition of acceleration:

By substituting the simplified notation for \(\Delta v\) and \(\Delta t\), we have

Solving for \(v\) yields

The above equation gives us insight into relationships among velocity, acceleration, and time. We can see that

Final velocity depends on the both acceleration and time

For zero acceleration, then the initial and final velocities are equal (i.e., \(v=v_o\))

If \(a<0\), then \(v<v_o\).

These relationships fit our intuition, which can be a good sign.

3.4.3.1. Example Problem: Calculating Final Velocity#

Exercise 3.6

The Problem

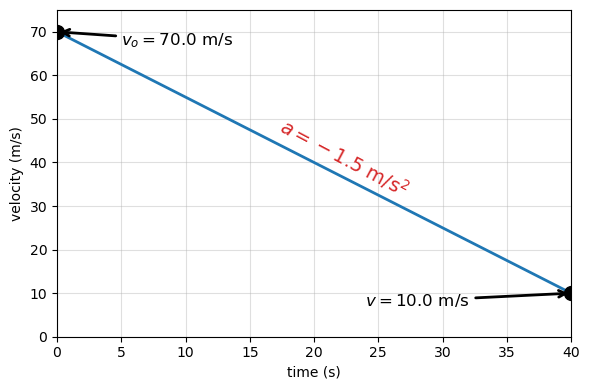

An airplane lands with an initial velocity of \(70.0\ \text{m/s}\) and then accelerates opposite to the motion at \(1.50\ \text{m/s}^2\) for \(40.0\ \text{s}\). What is its final velocity?

Fig. 3.6 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The Model

This is a one-dimensional kinematics problem with constant acceleration. We are given the initial velocity, the acceleration, and the elapsed time, and we are asked to find the final velocity.

We define the direction of motion to be positive. Because the airplane is slowing down, the acceleration points opposite the direction of motion and must therefore be negative.

Among the kinematic equations, the relation

directly connects the known quantities (\(v_o\) and \(a\)) to the unknown final velocity \(v\), making it the most efficient equation to use.

The Math

We begin by identifying the known quantities from the problem:

Initial velocity: \(v_o = 70.0\ \text{m/s}\)

Acceleration: \(a = -1.50\ \text{m/s}^2\)

Time interval: \(t = 40.0\ \text{s}\)

Substituting these values into the kinematic equation gives

The Conclusion

The final velocity of the airplane is \(10.0\ \text{m/s}\), which is significantly smaller than its initial velocity but still positive.

This means that after \(40.0\ \text{s}\) of negative acceleration, the airplane is still moving forward. Although reverse thrust could eventually bring the airplane to rest or even cause it to move backward, the given acceleration and time are not sufficient for that to occur here.

This example illustrates how the sign of the acceleration encodes direction and how constant acceleration steadily changes velocity over time.

The Verification

We can verify this result numerically by computing the velocity directly from the definition

using Python. Printing the result confirms the analytical calculation. A velocity–time plot with a constant negative slope would further illustrate how the velocity decreases linearly from \(70.0\ \text{m/s}\) to \(10.0\ \text{m/s}\) over the \(40.0\ \text{s}\) interval, consistent with uniform deceleration.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

v0 = 70.0 # initial velocity (m/s)

a = -1.50 # acceleration (m/s^2)

t_final = 40.0 # time (s)

# Compute final velocity

v_final = v0 + a * t_final

print(f"Final velocity after {t_final:.1f} s: v = {v_final:.1f} m/s")

#-----

# Time array (uniform spacing, intentional)

dt = 0.1

t = np.arange(0, t_final + dt, dt)

# Velocity as a function of time

v = v0 + a * t

# Create the figure using object-oriented style

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 4),dpi=100)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(t, v, linewidth=2)

ax.plot([0, t_final], [v0, v_final],'ko',ms=10,zorder=3)

# Labels and limits

ax.set_xlabel("time (s)")

ax.set_ylabel("velocity (m/s)")

ax.set_xlim(0, t_final)

ax.set_ylim(0, v0 + 5)

# Annotations instead of titles

ax.annotate(rf"$v_o = {v0:.1f}\ \mathrm{{m/s}}$",xy=(0, v0), fontsize=12,

xytext=(5, v0 - 3),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->",linewidth=2))

ax.annotate(rf"$v = {v_final:.1f}\ \mathrm{{m/s}}$",xy=(t_final, v_final), fontsize=12,

xytext=(t_final - 16, v_final - 3),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->",linewidth=2))

ax.text(17,32,rf"$a= {a:.1f}\ \mathrm{{m/s^2}}$",rotation=-28,color='tab:red',fontsize=14)

ax.grid(True,alpha=0.4)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Final velocity after 40.0 s: v = 10.0 m/s

3.4.4. Solving for Final Position with Constant Acceleration#

We can use the equation that defines the average velocity \(\bar{v}\) that is related to time and displacement \(\Delta x\) with the arithmetic definition of average velocity. This gives us 3 equations as

where \(a\) is a constant acceleration and using our simplified notation. The third equation can be substituted into the second equation to get

Now we substitute this expression for \(\bar{v}\) into the equation for displacement yielding

We can see the following relationships from the above equation:

Displacement depends on the time squared, when the accleration is not zero.

The form of the equation is a quadratic, where it should plot as a parabola.

If the acceleration is zero, then it reduces to \(x = x_o + v_o t\). the equation for displacement under constant velocity \(v_o\).

3.4.4.1. Example Problem: Calculating Displacement of an Accelerating Object#

Exercise 3.7

The Problem

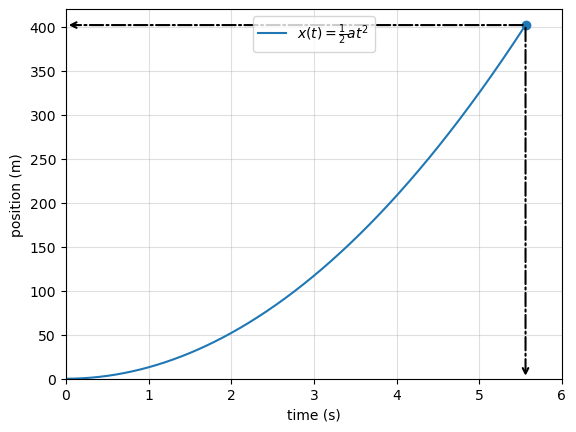

Dragsters can achieve an average acceleration of \(26.0\ \text{m/s}^2\). Suppose a dragster accelerates from rest at this rate for \(5.56\ \text{s}\). How far does it travel in this time?

Fig. 3.7 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The Model

We model the dragster as a particle undergoing one-dimensional motion with constant acceleration. The displacement can be found from the kinematic equation that relates position, velocity, acceleration, and time.

Because the dragster starts from rest, the initial velocity is zero. We choose the starting line of the race to be the origin so that the initial position is also zero. With these choices, the displacement depends only on the acceleration and the elapsed time.

The Math

For motion with constant acceleration, the position as a function of time is given by

Starting from rest implies \(v_o = 0\), and choosing the starting point as the origin gives \(x_o = 0\). The equation therefore simplifies to

Substituting the given values of acceleration and time,

Evaluating this expression gives \(x = 402\ \text{m}.\)

The Conclusion

The dragster travels a displacement of 402 m in \(5.56\ \text{s}\) while accelerating from rest.

Converting \(402\ \text{m}\) to miles shows that this distance is very close to one-quarter of a mile, the standard distance for drag racing. This confirms that the result is physically reasonable. Covering nearly a quarter mile in only a few seconds highlights the extreme accelerations achieved by top-tier dragsters.

If the dragster had an initial velocity, an additional term would contribute to the displacement, resulting in a much greater distance for the same acceleration and time.

The Verification

We can verify the analytical result numerically by computing the position as a function of time using the kinematic model for constant acceleration and then evaluating the displacement at the final time.

In addition, plotting the position versus time allows us to visually confirm that the displacement grows quadratically, as expected for motion starting from rest with constant acceleration. The final value read from the plot should agree with the analytical result of \(402\ \text{m}\).

# Verification of displacement for constant acceleration

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

a = 26.0 # acceleration (m/s^2)

t_final = 5.56 # final time (s)

# Time array (use arange for intentional spacing)

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, t_final + dt, dt)

# Position as a function of time (x0 = 0, v0 = 0)

x = 0.5 * a * t**2

# Print final displacement

print(f"Final displacement at t = {t_final:.2f} s: {x[-1]:.1f} m")

# Plot position vs time

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(t, x, label=r"$x(t)=\frac{1}{2}at^2$")

ax.scatter(t_final, x[-1], zorder=3)

# Arrows from endpoint to axes

ax.annotate("", xy=(t_final, 0), xytext=(t_final, x[-1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,ls='-.'))

ax.annotate("", xy=(0, x[-1]), xytext=(t_final, x[-1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,ls='-.'))

ax.set_xlabel("time (s)")

ax.set_ylabel("position (m)")

ax.legend(loc='upper center')

ax.set_xlim(0,6)

ax.set_ylim(0,420)

ax.grid(True,alpha=0.4)

plt.show()

Final displacement at t = 5.56 s: 401.9 m

3.4.5. Solving for Final Velocity from Distance and Acceleration#

Since the acceleration \(a\) is constant, we can instead solve for the time \(t\) and substitute into the equation for displacement. We have the following equations:

Substituting the first and second equations into the final equation (and performing some algebra) gives

Solving for \(v^2\), we get

Formatting Grouped Expressions

When fractions, powers, or stacked expressions get tall, ordinary parentheses or brackets can look too small.

LaTeX can automatically resize delimiters using \left and \right.

Automatic resizing with \left( \right)

Use these when the contents are tall (fractions, exponents, roots):

\(\left(\frac{1}{2}at^2\right)\)

\(\left(\frac{x_2-x_1}{t_2-t_1}\right)\)

\(\left(a+\frac{b}{c}\right)^2\)

LaTeX adjusts the size of the parentheses to match the height of the expression inside.

Automatic resizing with \left[ \right]

Brackets behave the same way and are often clearer for long expressions:

\(\left[\frac{x_2-x_1}{t_2-t_1}\right]\)

\(\left[\frac{1}{2}at^2\right]_{t=0}^{t=t_f}\)

\(\left[a+\left(\frac{b}{c}\right)^2\right]\)

Mixing delimiter types

You can mix parentheses and brackets to improve readability:

\(\left[\frac{(x_2-x_1)}{(t_2-t_1)}\right]\)

\(\left(a+\frac{b}{c}\right)\left(a-\frac{b}{c}\right)\)

Suppressing one side

If you only want one visible delimiter, use a period . on the other side:

\(\left.\frac{dx}{dt}\right|_{t=2\ \text{s}}\)

\(\left[\frac{1}{2}at^2\right.\)

Rule of thumb

Use ordinary

( )or[ ]for simple expressions.Use

\left( \right)or\left[ \right]whenever the expression contains fractions, roots, or stacked exponents.

This keeps your math clean, readable, and professional, especially in physics derivations.

Difference of Squares Identity

A very common algebra identity is

You can see it by distributing (or using FOIL to save a step):

This is useful for quickly simplifying expressions and for factoring quadratics that look like a difference of squares.

We can see the following relationships in this equation:

The final velocity depends on the acceleration and total displacement.

For a fixed acceleration, the stopping distance \((x-x_o)\) increases with the square of the velocity. It takes much farther to stop. This is shown by

\[ x-x_o = \frac{v_o^2}{2a} \propto v_o^2.\]

3.4.5.1. Example Problem: Calculating Final Velocity#

Exercise 3.8

The Problem

A dragster starts from rest and accelerates at an average rate of \(a=26.0\ \text{m/s}^2\). In the previous example, it traveled a displacement of \(\Delta x = x-x_o = 402\ \text{m}\).

Use a kinematic equation that does not involve time to find the dragster’s final velocity.

The Model

When time is not available (or not needed), we can connect velocity, acceleration, and displacement directly using the kinematic relation

This equation is ideal here because it relates the final velocity to the initial velocity, the constant acceleration, and the displacement.

The Math

The dragster starts from rest, so \(v_o=0\). The displacement is given as \(\Delta x = x-x_o = 402\ \text{m}\) and the acceleration is \(a=26.0\ \text{m/s}^2\).

Substituting into

gives

Taking the square root yields the final speed:

The Conclusion

The dragster’s final velocity \(v\) is approximately \(145\ \text{m/s}\). This is about \(145\times 3.6 \approx 522\ \text{km/h}\) (roughly \(324\ \text{mi/h}\)), which is consistent with the idea that drag racing involves extremely large accelerations over a short distance.

Because a square root mathematically has two signs, the equation technically allows \(v=\pm 145\ \text{m/s}\). We choose the positive value because the dragster is accelerating forward from rest, so its velocity points in the same direction as the acceleration.

The Verification

We can verify the result numerically in Python by computing \(v=\sqrt{2a\Delta x}\) and converting the speed into km/h and mi/h. We also include a quick consistency check by solving for the time from \(\Delta x =\tfrac{1}{2}at^2\) (which is valid here because the dragster starts from rest) and confirming that \(v=at\) matches the same final velocity.

import numpy as np

# Given values

a = 26.0 # m/s^2

dx = 402.0 # m

# Time-free kinematics: v^2 = v0^2 + 2 a dx, with v0 = 0

v = np.sqrt(2 * a * dx)

# Unit conversions

v_kmh = v * 3.6

v_mph = v * 2.2369362920544

print(f"Final velocity (time-free): v = {v:.1f} m/s")

print(f" = {v_kmh:.1f} km/h")

print(f" = {v_mph:.1f} mi/h")

# Optional consistency check using dx = (1/2) a t^2 (valid because v0 = 0)

t = np.sqrt(2 * dx / a)

v_check = a * t

print(f"\nConsistency check using x = (1/2) a t^2:")

print(f" t = {t:.3f} s")

print(f" v = a t = {v_check:.3f} m/s")

print(f" difference = {abs(v_check - v):.3e} m/s")

Final velocity (time-free): v = 144.6 m/s

= 520.5 km/h

= 323.4 mi/h

Consistency check using x = (1/2) a t^2:

t = 5.561 s

v = a t = 144.582 m/s

difference = 0.000e+00 m/s

3.4.6. Putting Equations Together#

Here’s a summary of the equations that we’ve developed thus far (under the assumption of constant \(a\)):

As we’ve seen already, some problems have two unknowns and thus, require two equations to solve for those unknowns. We must have as many equations as there are unknowns to solve a given situation.

Note

Consider how we can calculate the constant acceleration given the initial velocity \(v_o\), final velocity \(v\), and time interval \(t\). We can solve for the acceleration by

In the case where the time interval \(t\) is very small (i.e., \(t\rightarrow 0\)), the constant acceleration blows up (i.e., becomes infinite). Therefore, we must use a different method for calculating the acceleration \(a\).

Instead, we use the expression that depends on the velocities and displacement. This is given as

In the limit that both the velocity difference and displacement approach zero, the expression for acceleration becomes indeterminate. Resolving this limit leads naturally to the definition of instantaneous acceleration as a derivative, \(a=dv/dt\). This highlights the difference between average acceleration over a finite interval and instantaneous acceleration at a single moment in time.

A Note on “Infinite” Acceleration and What It Really Means

At first glance, both expressions for acceleration can seem to “blow up” (become infinite):

Let’s look at what this really means.

Time-based form

If the change in velocity (v - v_o) is small and the time (t) is finite, the acceleration is small.

If (v = v_o), then (a = 0): there is no acceleration.

But if we try to change velocity by a finite amount in an extremely short time ((t \rightarrow 0)), the acceleration becomes very large.

This situation does not represent realistic motion. It corresponds to an instantaneous jump in velocity, which would require an infinite force.

Displacement-based form

If the velocity change is small and the displacement is finite, the acceleration is small.

If (v = v_o), the numerator is zero and (a = 0).

If a finite velocity change occurs over almost no distance, the acceleration again becomes very large.

This describes another unphysical situation: a sharp change in motion over essentially zero distance.

How calculus resolves the issue

When both the change in velocity and the time (or displacement) become small together, these expressions take the indeterminate form (0/0). In that limit, acceleration must be defined using a derivative:

This definition ensures that acceleration remains finite for smooth, realistic motion.

Key takeaway

Very large accelerations arise when velocity changes too abruptly.

Real objects change velocity smoothly, not instantaneously.

Calculus replaces finite differences with derivatives to correctly describe motion at an instant.

This is why sharp corners on velocity graphs imply infinite acceleration and why real motion curves are smooth.

Example Problem: Calculating Time

Exercise 3.9 (Calculating Time)

The Problem

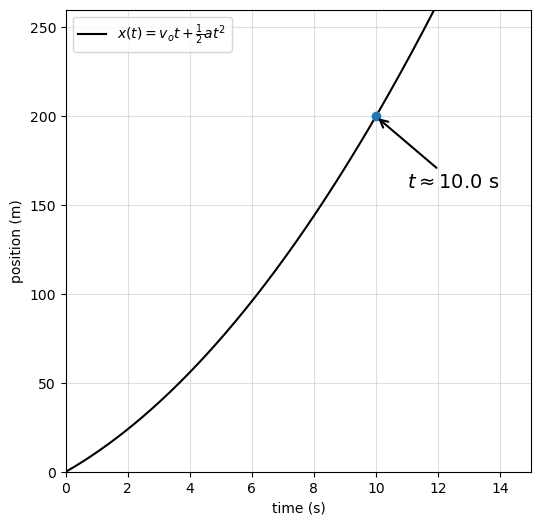

A car merges into freeway traffic on a straight, \(200\)-m-long on-ramp. If its initial velocity is \(v_o = 10.0\ \text{m/s}\) and it accelerates uniformly at \(a = 2.00\ \text{m/s}^2\), how long does it take the car to travel the 200 m up the ramp?

Fig. 3.8 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The Model

We are asked to solve for time when position, initial velocity, and constant acceleration are known. The kinematic equation

is well suited for this situation because it contains only one unknown, the time \(t\). Substituting known values will lead to a quadratic equation, which we must solve carefully and interpret physically.

The Math

We begin by identifying the known quantities:

Substituting into the position equation gives

Simplifying into standard quadratic form,

We now apply the quadratic formula,

with \(a = 1\), \(b = 10\), and \(c = -200\):

This yields two solutions,

The negative time corresponds to a moment before the motion began and has no physical meaning in this context. We therefore discard it and accept the physical solution, \(\boxed{t = 10.0\ \text{s}}\).

The Conclusion

The car takes 10.0 s to travel the \(200\)-m on-ramp. This value is reasonable for a typical freeway merge and illustrates an important feature of kinematics: equations that contain squared variables often produce multiple mathematical solutions, but only those consistent with the physical situation should be kept.

The Verification

We can verify this result numerically by computing the position as a function of time and checking when it reaches \(200\) m. Evaluating

at \(t = 10.0\ \text{s}\) gives

confirming the analytical solution.

# Verification of time for an accelerating car on a freeway ramp

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

v0 = 10.0 # initial velocity (m/s)

a = 2.00 # acceleration (m/s^2)

x_target = 200.0 # displacement (m)

# Time array

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, 15 + dt, dt)

# Position as a function of time

x = v0 * t + 0.5 * a * t**2

# Find the time when x is closest to 200 m

idx = np.argmin(np.abs(x - x_target))

t_solution = t[idx]

x_solution = x[idx]

# Print numerical result

print(f"Time to reach {x_target:.0f} m: t ≈ {t_solution:.2f} s")

print(f"Position at that time: x ≈ {x_solution:.1f} m")

# Plot position vs time

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6,6),dpi=100)

ax.plot(t, x, 'k-', lw=1.5,label=r"$x(t) = v_o t + \frac{1}{2} a t^2$")

ax.scatter(t_solution, x_solution, zorder=3)

# Annotate solution point

ax.annotate(

r"$t \approx 10.0\ \mathrm{s}$",xy=(t_solution, x_solution),

xytext=(t_solution + 1.0, x_solution - 40), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->",lw=1.5),fontsize=14)

ax.set_xlabel("time (s)")

ax.set_ylabel("position (m)")

ax.set_xlim(0, 15)

ax.set_ylim(0, 260)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

plt.show()

Time to reach 200 m: t ≈ 10.00 s

Position at that time: x ≈ 200.0 m

3.4.6.1. Example Problem: Acceleration of a Spaceship#

Exercise 3.10

The Problem

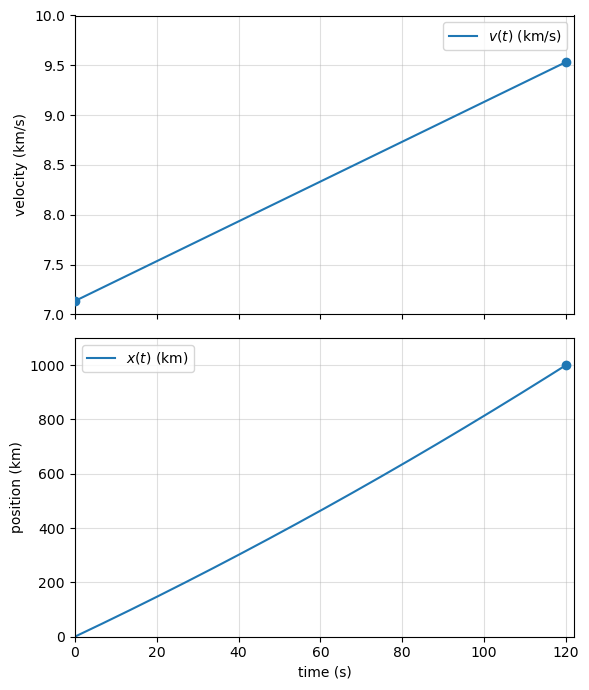

A spaceship has left Earth’s orbit and is on its way to the Moon. It accelerates at \(20.0\ \text{m/s}^2\) for \(2\ \text{min}\) and covers a distance of \(1000\ \text{km}\). What are the initial and final velocities of the spaceship?

The Model

The motion is one-dimensional with constant acceleration, so we can use the kinematic equations that relate position, velocity, acceleration, and time. Because both the initial and final velocities are unknown, no single equation is sufficient by itself. Instead, we solve two kinematic equations simultaneously.

We first use the displacement equation to determine the initial velocity. Once the initial velocity is known, we substitute it into the velocity–time equation to find the final velocity.

The Math

We begin with the displacement equation,

Rewriting this to solve for the initial velocity gives

We need to either convert the distance from \({\rm} km \rightarrow {\rm m}\) or the acceleration from \({\rm m/s^2}\rightarrow {\rm km/s^2}\). It seems like the latter will be easier because \(1000\ {\rm km} = 10^6\ {\rm m}\) and it will be easier to interpret if the numbers are smaller. Note: this choice is a matter of convenience rather than a strict right or wrong approach.

The given values are

Substituting these into the equation,

Evaluating the acceleration term,

Solving for the initial velocity,

Final velocity

We now use the velocity–time relation,

Substituting the known values,

which gives

The Conclusion

The spaceship begins its acceleration phase with an initial velocity of approximately

and reaches a final velocity of

This problem illustrates an important point in kinematics: when more than one quantity is unknown, solving a problem may require combining multiple kinematic equations rather than relying on a single substitution.

The Verification

We can verify the analytical results numerically by directly computing the position and velocity of the spaceship under constant acceleration.

Using the known acceleration and time interval, we:

Compute the initial velocity from the displacement equation.

Compute the final velocity from the velocity–time relation.

Plot both velocity and position as functions of time to confirm that:

The position at \(t = 120\,\text{s}\) is \( 1000\,\text{km} \).

The velocity increases linearly from \( v_o \) to \(v\).

The printed numerical values match the analytical results, providing an independent verification.

# Verification of spaceship acceleration problem

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

a = 0.02 # km/s^2

t_final = 120.0 # s

x_final = 1.0e3 # km

# Time array

dt = 0.1

t = np.arange(0, t_final + dt, dt)

# Solve for initial velocity from displacement equation

v0 = (x_final - 0.5 * a * t_final**2) / t_final

# Velocity and position as functions of time

v = v0 + a * t

x = v0 * t + 0.5 * a * t**2

# Print results

print(f"Initial velocity v0 = {v0:.1f} km/s")

print(f"Final velocity v = {v[-1]:.1f} km/s")

print(f"Final position x = {x[-1]:.1e} km")

# Create plots

fig, axes = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(6, 7), sharex=True)

# Velocity plot

axes[0].plot(t, v,label='$v(t)$ (km/s)')

axes[0].scatter([0, t_final], [v0, v[-1]], zorder=3)

axes[0].set_ylabel("velocity (km/s)")

axes[0].legend()

axes[0].grid(True, alpha=0.4)

axes[0].set_ylim(7,10)

axes[0].set_xlim(0,122)

# Position plot

axes[1].plot(t, x, label='$x(t)$ (km)')

axes[1].scatter(t_final, x[-1], zorder=3)

axes[1].set_xlabel("time (s)")

axes[1].set_ylabel("position (km)")

axes[1].legend()

axes[1].grid(True, alpha=0.4)

axes[1].set_ylim(0,1100)

axes[1].set_xlim(0,122)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Initial velocity v0 = 7.1 km/s

Final velocity v = 9.5 km/s

Final position x = 1.0e+03 km

3.4.7. Two-Body Pursuit Problems#

In a two-body pursuit problem, the motions of the objects are coupled (i.e., the unknown depends on the motion of both objects). To solve these problems we write the equations of motion for each object and then solve them simultaneously to find the unknown.

Fig. 3.9 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The time and distance required for car 1 to catch car 2 (see Fig. 3.9) depends on the initial distance car 1 is from car 2 as well as the velocities of both cars and the acceleration of car 1.

The initial distance defines how far car 1 needs to travel to catch up.

The velocities of both cars and the acceleration of car 1 define the relative motion of the cars. If

\[\begin{align*} \begin{cases} \text{car 1 never catches car 2}; \quad &a_1\leq 0\ \&\ v_1 < v_2, \\ \text{car 1 keeps pace with car 2}; \quad &a_1 = 0\ \&\ v_1 = v_2, \\ \text{car 1 catches car 2}; \quad &a_1>0\ \&\ v_1 > v_2. \end{cases} \end{align*}\]

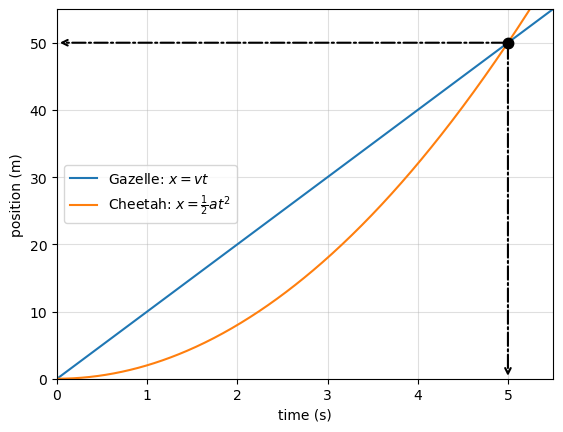

3.4.7.1. Example Problem: Cheetah Catching a Gazelle#

Exercise 3.11

A cheetah waits in hiding behind a bush. THe cheetah spots a gazelle running past at \(10\ \text{m/s}\). At the instant the gazelle passes the cheetah, the cheetah accelerates from rest at \(4.0\ \text{m/s}^2\) to catch the gazelle. a. How long does it take for the cheetah to catch the gazelle? b. What is the displacement of the gazelle and the cheetah?

The Model

This is a two-object pursuit problem in one dimension. The cheetah and the gazelle start at the same position, but they move differently:

The gazelle \(\rm G\) moves with constant velocity.

The cheetah \(\rm C\) starts from rest and accelerates uniformly.

The key idea is that when the cheetah catches the gazelle, both animals are at the same position at the same time. This shared position provides the common parameter that links their equations of motion.

The Math

We choose the origin at the point where the gazelle passes the cheetah, so \(x_o = 0\) for both animals.

Gazelle

The gazelle moves at constant velocity \(v_{\rm G} = 10\ \text{m/s}\), so its position is

Cheetah

The cheetah starts from rest and accelerates at \(a_{\rm C} = 4.0\ \text{m/s}^2\), so its position is

Catch condition

At the instant the cheetah catches the gazelle, their positions are equal:

Solving for time,

Substituting the given values,

Displacement

We can now compute the displacement using either animal.

For the cheetah,

For the gazelle,

Both give the same result, as expected.

The Conclusion

The cheetah catches the gazelle after 5.0 s, at a distance of 50 m from the starting point. This problem demonstrates how two different equations of motion can be linked by a shared physical condition; in this case, equal position at the same time.

The Verification

We can verify the analytical solution numerically by computing the positions of the cheetah and gazelle as functions of time and identifying when they intersect.

The numerical results confirm that both positions become equal at \(t = 5.0\ \text{s}\) and \(x = 50\ \text{m}\), providing an independent check of the algebraic solution.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given parameters

v_G = 10.0 # speed of gazelle in m/s

a_C = 4.0 # acceleration of cheetah in m/s^2

# Time array

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, 6 + dt, dt)

# Positions

x_G = v_G * t

x_C = 0.5 * a_C * t**2

# Find catch time (minimum separation)

idx = np.where(np.abs(x_G- x_C)<1e-4)[0]

t_catch = t[idx][1] # need [1] to exclude starting time

x_catch = x_G[idx][1] # need [1] to exclude starting separation

print(f"Cheetah catches gazelle at t = {t_catch:.2f} s")

print(f"Displacement at catch: x = {x_catch:.1f} m")

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots()

ax.plot(t, x_G, label="Gazelle: $x=vt$")

ax.plot(t, x_C, label="Cheetah: $x=\\frac{1}{2}at^2$")

ax.plot(t_catch, x_catch, 'k.',ms=15,zorder=3)

# Arrows from endpoint to axes

ax.annotate("", xy=(t_catch, 0), xytext=(t_catch, x_catch),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,ls='-.'))

ax.annotate("", xy=(0, x_catch), xytext=(t_catch, x_catch),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5,ls='-.'))

ax.set_xlabel("time (s)")

ax.set_ylabel("position (m)")

ax.legend(loc='center left')

ax.grid(alpha=0.4)

ax.set_xlim(0,5.5)

ax.set_ylim(0,55)

plt.show()

Cheetah catches gazelle at t = 5.00 s

Displacement at catch: x = 50.0 m

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.animation import FuncAnimation

from IPython.display import HTML

# ----------------------------

# Given parameters

# ----------------------------

v_G = 10.0 # speed of gazelle in m/s

a_C = 4.0 # acceleration of cheetah in m/s^2

# Time array (use arange, not linspace)

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, 5.01 + dt, dt)

# Positions

x_G = v_G * t

x_C = 0.5 * a_C * t**2

# Catch time (exclude the starting time)

idx = np.where(np.abs(x_G - x_C) < 1e-4)[0]

t_catch = t[idx][1] # [1] excludes the trivial t=0 intersection

x_catch = x_G[idx][1]

print(f"Cheetah catches gazelle at t = {t_catch:.2f} s")

print(f"Displacement at catch: x = {x_catch:.1f} m")

# Find the animation frame closest to t_catch

i_catch = int(np.argmin(np.abs(t - t_catch)))

# ----------------------------

# Animation setup

# ----------------------------

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(9, 2.6))

xmax = max(x_G[-1], x_C[-1])

ax.set_xlim(-0.03 * xmax, 1.03 * xmax)

ax.set_ylim(-1.0, 1.0)

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xlabel("position x (m)")

ax.grid(alpha=0.35)

# "Track" line

ax.hlines(0, 0, xmax, alpha=0.2)

# Dots (gazelle blue, cheetah orange)

dot_G, = ax.plot([], [], "o", ms=10, label="Gazelle")

dot_C, = ax.plot([], [], "o", ms=10, label="Cheetah")

# Catch highlight: ring + label + guide arrows

ring, = ax.plot([], [], "o", ms=18, mfc="none", mec="k", mew=2, zorder=4)

txt = ax.text(0, 0.55, "", ha="center", va="bottom")

# Two arrows from catch point to axes (hidden until catch)

# We'll draw them as line segments with arrowheads.

arr_to_x = ax.annotate("",xy=(0, 0), xytext=(0, 0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5, ls="-."))

arr_to_t = ax.annotate("",xy=(0, 0),xytext=(0, 0),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=1.5, ls="-."))

arr_to_x.set_visible(False)

arr_to_t.set_visible(False)

ax.legend(loc="upper left")

# small vertical offset so they don't overlap visually

y_G, y_C = 0.25, -0.25

def init():

dot_G.set_data([], [])

dot_C.set_data([], [])

dot_G.set_color("tab:blue")

dot_C.set_color("tab:orange")

ring.set_data([], [])

txt.set_text("")

arr_to_x.set_visible(False)

arr_to_t.set_visible(False)

return dot_G, dot_C, ring, txt, arr_to_x, arr_to_t

def update(i):

# Move dots

dot_G.set_data([x_G[i]], [y_G])

dot_C.set_data([x_C[i]], [y_C])

# Default state

ring.set_data([], [])

txt.set_text("")

arr_to_x.set_visible(False)

arr_to_t.set_visible(False)

dot_G.set_markersize(10)

dot_C.set_markersize(10)

# Highlight catch frame

if i == i_catch:

dot_G.set_markersize(14)

dot_C.set_markersize(14)

ring.set_data([x_catch], [0.0])

txt.set_position((x_catch, 0.55))

txt.set_text(f"CATCH!\n$t={t_catch:.2f}\\,\\mathrm{{s}}$ $x={x_catch:.1f}\\,\\mathrm{{m}}$")

# Arrows from catch point to axes

arr_to_x.xy = (x_catch, 0.0) # arrow head on x-axis

arr_to_x.xyann = (x_catch, 0.35) # start above

arr_to_x.set_visible(True)

arr_to_t.xy = (0.0, 0.0) # arrow head at origin

arr_to_t.xyann = (x_catch, 0.0) # start at catch point on axis line

arr_to_t.set_visible(True)

return dot_G, dot_C, ring, txt, arr_to_x, arr_to_t

anim = FuncAnimation(fig,update,frames=len(t),init_func=init,interval=40,blit=True)

plt.close(fig)

HTML(anim.to_jshtml())

Cheetah catches gazelle at t = 5.00 s

Displacement at catch: x = 50.0 m

3.5. Free Fall#

3.5.1. Gravity#

Until Galileo Galilei showed otherwise, people believed that a heavier object has a greater acceleration in a free fall. We know now that this is not the case.

In the absence of air resistance, heavy objects arrive at the ground at the same time as lighter objects when dropped from the same height.

In the real world, air resistance can cause a lighter object to fall slower than a heavier object of the same size. A tennis ball reaches the ground after a baseball dropped at the same time, although the difference is not large. Air resistance opposes the motion of an object through the air and friction between objects also apposes motion between them.

Free fall is when an object falls without air resistance or friction. The force of gravity causes objects to fall toward the center of the Earth, where this acceleration is also called the acceleration due to gravity.

Near Earth’s surface (or for small changes in altitude) the acceleration due to gravity is constant, which means we can apply the kinematic equations to any falling object (where air resistance and friction are negligible), including spherical cows.

Acceleration due to gravity is given its own symbol \(g\), where it is nearly constant at any location on Earth’s surface with the average value

The value of \(g\) can vary from \(9.78 - 9.83\ {\rm m/s^2}\) depending on latitude, altitude, underlying geological formations, and local topography. Here we use its average value rounded to two significant figures.

The direction of acceleration due to gravity \(g\) is defined to be downward (i.e., toward Earth’s center). Its direction defines what we call vertical.

Note

The acceleration \(a\) in the kinematic equations has the value \(+g\) or \(-g\) depending on how we define our coordinate system. If we define the

upward direction as positive, then \(a=-g=-9.81\ {\rm m/s^2}\).

downward direction as positive, then \(a=g=9.81\ {\rm m/s^2}\).

3.5.2. One-Dimensional Motion Involving Gravity#

Consider vertical (up-and-down) motion with no air resistance or friction, where these assumptions mean the velocity is also vertical. There are some statements about the initial velocity of an object as it enters or leaves free fall. The object is in free fall after it has left contact with whatever held or threw it.

If an object is dropped, we know the initial velocity is zero when in free fall (i.e., \(v_o = 0\)).

If the object is thrown, it has the same speed in free fall as it did before it was released (i.e., \(v_o\) is defined at release).

When in free fall, the motion is 1D and has constant constant acceleration of magnitude \(g\). When the object comes in contact with the ground (or any other object), it is no longer in free fall (i.e., \(a \neq g\)).

We represent the vertical displacement with the symbol \(y\) and write the following kinematic equations for objects in free fall. We assume that the positive direction is upward, which gives

When solving free fall problems, its helpful to follow this strategy:

Decide on the sign of \(g\) (i.e., is positive upward or downward). In some problems, it may be useful to have \(+g\) indicating the positive direction is downward.

DRAW A SKETCH of the problem. Visualizing the problem can be a useful first step. Don’t worry about artistic quality.

Identify the knowns and unknowns from the problem description.

Match the kinematic equations with the knowns and unknowns.

3.5.2.1. Example Problem: Free Fall of a Ball#

Exercise 3.12

Free Fall of a Ball

Fig. 3.10 shows the positions of a ball, at \(1\)-s intervals, with an initial velocity of \(4.9\ {\rm m/s}\) downward, that is thrown from the top of a \(98\)-m-high building. (a) How much time elapses before the ball reaches the ground? (b) What is the velocity when it arrives at the ground?

Fig. 3.10 Image Credit: Openstax.#

The Model

We choose a one-dimensional vertical coordinate system with the origin at the top of the building. The positive direction is upward and the negative direction is downward.

With this choice:

Initial position: \(y_o = 0\)

Final position (ground): \(y = -98\ \text{m}\)

Initial velocity: \(v_o = -4.9\ \text{m/s}\)

Acceleration due to gravity: \(a = -g = -9.81\ \text{m/s}^2\)

Because the acceleration is constant, we use the standard kinematic equations for uniformly accelerated motion.

The Math

(a) Time to reach the ground

We begin with the position–time equation,

Substituting the known values gives

Rearranging,

Solving this quadratic equation yields two roots,

The negative root corresponds to a time before the ball was released and is not physically meaningful. Therefore, the time for the ball to reach the ground is \(t = 4.0\ \text{s}.\)

(b) Velocity at the ground

We now use the velocity–time relation,

The Conclusion

The ball reaches the ground after 4.0 s and has a velocity of \(44\ \text{m/s}\) downward just before impact.

This example highlights the importance of carefully choosing a coordinate system and interpreting solutions to quadratic equations. When solving for time, mathematical solutions must always be checked for physical meaning. The negative time solution represents a different physical situation and is correctly discarded.

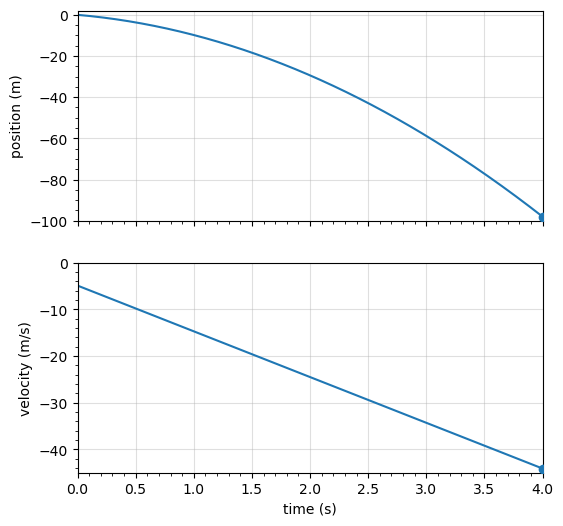

The Verification

We can verify the analytical results numerically by directly computing the position and velocity of the ball under constant acceleration.

Using the known acceleration and initial velocity, we:

Compute the position as a function of time and identify when it reaches \(-98\ \text{m}\).

Compute the velocity as a function of time.

Confirm that the numerical values at the impact time match the analytical results.

The numerical results provide an independent check of the solution.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

y0 = 0.0 # initial position (m)

v0 = -4.9 # initial velocity (m/s)

a = -9.8 # acceleration (m/s^2)

# Time array

dt = 0.01

t = np.arange(0, 6 + dt, dt)

# Position and velocity

y = y0 + v0*t + 0.5*a*t**2

v = v0 + a*t

# Find impact time (closest point to y = -98 m)

idx = np.argmin(np.abs(y + 98))

t_hit = t[idx]

v_hit = v[idx]

print(f"Time to reach ground: {t_hit:.2f} s")

print(f"Velocity at ground: {v_hit:.1f} m/s")

# Plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(2, 1, figsize=(6, 6), sharex=True)

ax[0].plot(t, y)

ax[0].scatter(t_hit, y[idx], zorder=3)

ax[0].set_ylabel("position (m)")

ax[0].grid(alpha=0.4)

ax[0].set_ylim(-100,2)

ax[0].set_xlim(0,4)

ax[0].minorticks_on()

ax[1].plot(t, v)

ax[1].scatter(t_hit, v_hit, zorder=3)

ax[1].set_xlabel("time (s)")

ax[1].set_ylabel("velocity (m/s)")

ax[1].grid(alpha=0.4)

ax[1].set_ylim(-45,-0)

ax[1].set_xlim(0,4)

ax[1].minorticks_on()

plt.show()

Time to reach ground: 4.00 s

Velocity at ground: -44.1 m/s

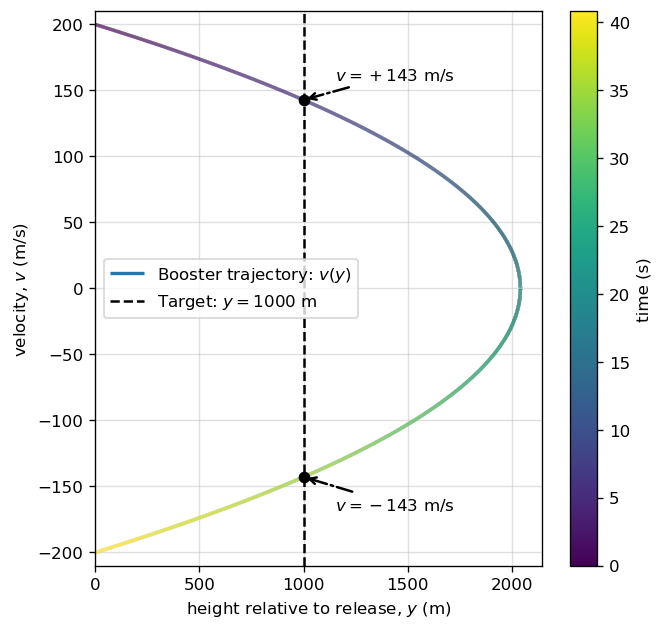

3.5.2.2. Example Problem: Rocket Booster Motion#

Exercise 3.13

The Problem

A small rocket blasts off and travels straight upward. When at a height of \(5.0\ \text{km}\) and velocity of \(200.0\ \text{m/s}\), it releases its booster. (a) What is the maximum height the booster attains? What is the velocity of the booster at a height of \(6.0\ \text{km}\)? Neglect air resistance.

The Model

After the booster is released, it moves under the influence of constant gravitational acceleration only. We choose a one-dimensional vertical coordinate system with:

Positive direction upward

Acceleration due to gravity \(g = 9.8\ \text{m/s}^2\) downward

To simplify the mathematics, we take the point of booster release as the origin of our coordinate system. This allows us to work with relative heights instead of absolute altitude above Earth. The Earth is \({\sim}6400\ {\rm km}\) in radius, where an altitude of a few \(\rm km\) is not enough to dramatically change the value of \(g\).

We will use the kinematic relation that connects velocity and displacement without involving time,

The Math

At the instant of release,

(a) Maximum height

At the maximum height, the booster momentarily comes to rest, so \(v = 0.\) Substituting into the velocity–displacement equation,

Solving for \(y\),

Substituting numerical values,