4. Motion in 2D and 3D#

4.1. Displacement and Velocity Vectors#

4.1.1. Displacement Vector#

To describe motion in 2D and 3D, we must first define a coordinate system, including a convention of axes. Recall that the sign of the acceleration due to gravity was determined by the convention that we chose. We usually use the Cartesian coordinate system to locate a particle at point \(P(x,y,z)\) in 3 dimensions. If the particle is moving , the variables \(x,y,z\) are functions of time \(t\).

The position vector \(\vec{r}(t)\) locates the point P at time t from the origin, by

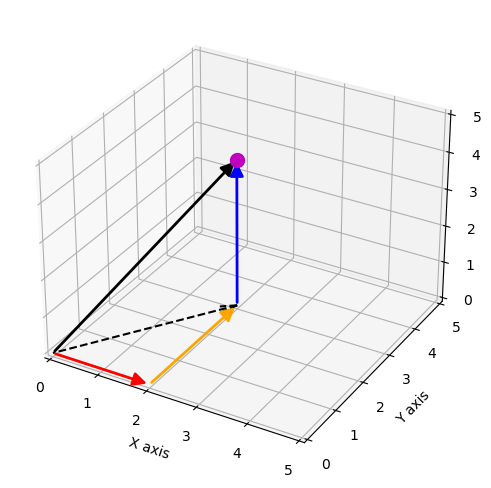

Fig. 4.1 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

Fig. 4.1 shows the position vector \(\vec{r}(t)\) for a particle located at a time \(t\). Note that the orientation of the coordinate system follows the right-hand rule.

We can now define the 3D displacement vector \(\Delta \vec{r}\) as the difference between the position vector \(\vec{r}(t_2)\) at time \(t_2\) and the initial position vector \(\vec{r}(t_1)\) at time \(t_1\), or

Three dimensional vector addition is performed in the same way as in 2D, by adding the corresponding components or graphically by using the head-to-tail method.

Fig. 4.2 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

See the python code below that demonstrates how to plot a 3D vector in matplotlib.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.patches import FancyArrowPatch

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d import proj3d

# Custom class to draw true 3D arrows (matplotlib does not support these natively)

class Arrow3D(FancyArrowPatch):

def __init__(self, xs, ys, zs, mutation_scale=20, lw=2, arrowstyle="-|>", **kwargs):

super().__init__((0, 0), (0, 0),mutation_scale=mutation_scale,lw=lw, arrowstyle=arrowstyle, **kwargs)

self._verts3d = xs, ys, zs

def do_3d_projection(self, renderer=None):

xs, ys, zs = proj3d.proj_transform(*self._verts3d, self.axes.M)

self.set_positions((xs[0], ys[0]), (xs[1], ys[1]))

return np.min(zs)

# Set up the 3D plotting environment

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 6), dpi=100,

subplot_kw=dict(projection="3d"))

# Define the vector components and endpoints

x0, y0, z0 = 0, 0, 0 # vector tail

u, v, w = 2, 3, 4 # vector components

x1, y1, z1 = u, v, w # vector head

# Draw the vector and its component projections

ax.add_artist(Arrow3D([x0, x1], [y0, y1], [z0, z1], color="k"))

ax.add_artist(Arrow3D([x0, x1], [y0, y0], [z0, z0], color="r"))

ax.add_artist(Arrow3D([x1, x1], [y0, y1], [z0, z0], color="orange"))

ax.add_artist(Arrow3D([x1, x1], [y1, y1], [z0, z1], color="b"))

# Plot the x-y vector

ax.quiver(x0, y0, z0, u, v, 0, color="k",

ls="--", arrow_length_ratio=0.1)

ax.plot(x1, y1, z1, "mo", ms=10, zorder=5) # mark the endpoint

# Formatting

ax.set_xlim(0, 5); ax.set_ylim(0, 5); ax.set_zlim(0, 5)

ax.set_xlabel("X axis"); ax.set_ylabel("Y axis"); ax.set_zlabel("Z axis")

plt.show()

4.1.1.1. Example Problem: Polar Orbiting Satellite#

Exercise 4.1

The Problem

A satellite is in a circular polar orbit around Earth at an altitude of \(400\ \text{km}\), meaning it passes directly over the North and South Poles. What are the magnitude and direction of the displacement vector from when the satellite is directly over the North Pole to when it is at latitude \(-45^\circ\)?

The Model

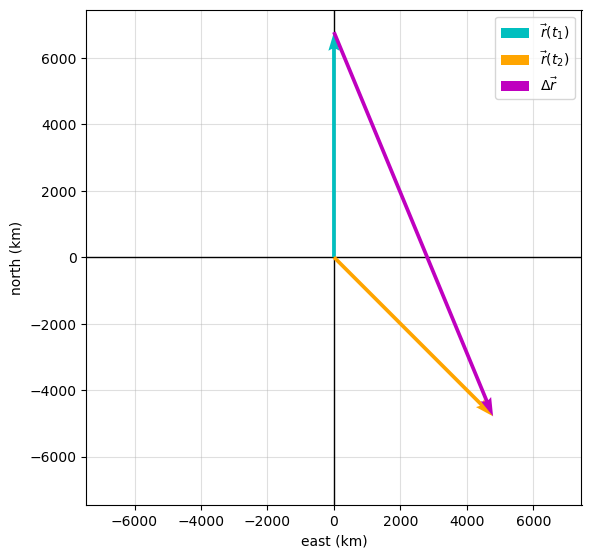

Although the satellite moves along a curved path, the displacement depends only on the initial and final positions. We therefore model the motion using position vectors drawn from the center of Earth, which we take to be the origin of a Cartesian coordinate system.

We choose the \(y\)-axis to point north and the \(x\)-axis to point east. With this choice, the displacement vector is found by subtracting the initial position vector from the final position vector.

The Math

The radius of Earth is \(6370\ \text{km}\), and the satellite orbits at an altitude of \(400\ \text{km}\). The radius of the orbit is therefore

When the satellite is directly over the North Pole, its position vector points entirely in the \(+y\) direction. The initial position vector is

At latitude \(-45^\circ\), the satellite’s position vector makes an angle of \(-45^\circ\) with the \(+x\)-axis. The final position vector is therefore

Evaluating the trigonometric functions gives

The displacement vector is the difference between the final and initial position vectors,

The magnitude of the displacement is

The direction of the displacement relative to the \(+x\)-axis is

The Conclusion

The displacement of the satellite from the North Pole to latitude \(-45^\circ\) has a magnitude of

and points \(67.5^\circ\) south of east. Even though the satellite follows a curved path along its orbit, the displacement represents the straight-line separation between the two positions.

The Verification

We can verify the analytical result numerically by computing the position vectors and their difference using Python. The magnitude and direction obtained numerically match the analytical values, confirming the result.

# Verification of polar orbit displacement problem

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

R_earth = 6370.0 # km

h = 400.0 # km

r = R_earth + h # km

lat2 = -45.0 # degrees

# Position vectors (x is east, y is north)

r1 = np.array([0.0, r]) # over North Pole

r2 = r * np.array([np.cos(np.radians(lat2)),

np.sin(np.radians(lat2))])

# Displacement vector

dr = r2 - r1

# Magnitude and direction (angle from +x axis)

dr_mag = np.linalg.norm(dr)

theta = np.degrees(np.arctan2(dr[1], dr[0]))

# Print results

print(f"Orbit radius r = {r:.0f} km")

print(f"Displacement |dr| = {dr_mag:.2e} km")

print(f"Direction angle theta = {theta:.1f} deg")

# Create a vector plot

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(6, 6))

# Plot axes and vectors

ax.axhline(0, lw=1,color='k',zorder=2)

ax.axvline(0, lw=1,color='k',zorder=2)

ax.quiver(0, 0, r1[0], r1[1], color='c', zorder=5,

angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, label=r'$\vec{r}(t_1)$')

ax.quiver(0, 0, r2[0], r2[1], color='orange', zorder=5,

angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, label=r'$\vec{r}(t_2)$')

ax.quiver(r1[0], r1[1], dr[0], dr[1], color='m', zorder=5,

angles='xy', scale_units='xy', scale=1, label=r'$\Delta\vec{r}$')

# Formatting

ax.set_aspect('equal', adjustable='box')

lim = 1.1 * r

ax.set_xlim(-lim, lim)

ax.set_ylim(-lim, lim)

ax.set_xlabel("east (km)")

ax.set_ylabel("north (km)")

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

ax.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Orbit radius r = 6770 km

Displacement |dr| = 1.25e+04 km

Direction angle theta = -67.5 deg

4.1.2. Velocity Vector#

Previously, we defined the velocity in 1D through the derivative of \(x(t)\). To expand it to 2D or 3D, we simply replace \(x(t) \rightarrow \vec{r}(t)\) to get

The vectors \(\vec{r}(t)\) and \(\vec{r}(t + \Delta t)\) represent instantaneous states of the displacement vector \(\vec{r}\) at two times. The path of a particle located by the vector is the resultant (difference) vector \(\Delta \vec{r}\), which connects from head-to-head (see Fig. 4.3).

Fig. 4.3 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

The velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}\) can also be written in components, where each component is now time-dependent (\(v_x(t),\ v_y(t),\ v_z(t)\)). Mathematically, the progression from the displacement to the velocity vector is given by

where

The average velocity \(\bar{v}\) was described as a vector in the previous chapter, and there is a 2D or 3D equivalent given as

Typesetting the Velocity Vector

To make distinction between the velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}\) and its components (\(v_x,\ v_y,\ v_z\)), we use the roman font command \rm. This is a convention just to make things clearer.

4.1.2.1. Example Problem: Calculating the Velocity Vector#

Exercise 4.2

The Problem

The position function of a particle is

\(\vec{r}(t) = (2.0t^2)\ \hat{i} + (2.0 + 3.0t)\ \hat{j} + 5.0\ \hat{k}\ \text{km}.\) (a) What is the instantaneous velocity vector and speed at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\)? (b) What is the average velocity between \(t = 1.0\ \text{s}\) and \(t = 3.0\ \text{s}\)?

The Model

The velocity of a particle is obtained by taking the time derivative of its position vector. The instantaneous velocity is evaluated at a specific time, while the average velocity is defined as the change in position divided by the elapsed time interval.

We compute both quantities using vector calculus and then compare the results.

The Math

The velocity vector is the time derivative of the position vector,

Taking the derivative of each component gives

Evaluating this expression at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\),

The speed is the magnitude of the velocity vector,

To find the average velocity, we use its definition,

Evaluating the position vector at \(t_1 = 1.0\ \text{s}\) and \(t_2 = 3.0\ \text{s}\),

Substituting into the average velocity expression,

Symbolic Differentiation in Python

SymPy can differentiate symbols instead of numbers. If you write each component of \(\vec{r}(t)\) as a symbolic expression in \(t\), then diff(...) returns the derivative exactly. After that, you can substitute a specific value like \(t=2.0\) using .subs(t, 2.0) and convert to a float with float(...).

This is especially useful when \(\vec{r}(t)\) is complicated and you want to avoid algebra mistakes.

The Conclusion

At \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\), the instantaneous velocity of the particle is

with a speed of \(9.9\ \text{km/s}\). The average velocity between \(t = 1.0\ \text{s}\) and \(t = 3.0\ \text{s}\) is equal to the instantaneous velocity at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\) because the velocity varies linearly with time.

The Verification

We can verify these results numerically by differentiating the position function and evaluating both the instantaneous and average velocities directly using Python.

# Verification of velocity vector problem

import numpy as np

# Define the position function

def r(t):

return np.array([2.0*t**2, 2.0 + 3.0*t, 5.0])

# Times

t1 = 1.0

t2 = 3.0

t_eval = 2.0

# Instantaneous velocity (analytical derivative)

v_inst = np.array([4.0*t_eval, 3.0, 5.0])

speed = np.linalg.norm(v_inst)

# Average velocity

v_avg = (r(t2) - r(t1)) / (t2 - t1)

# Print results

print(f"Instantaneous velocity at t = 2.0 s: {v_inst} km/s")

print(f"Speed at t = 2.0 s: {speed:.1f} km/s")

print(f"Average velocity from 1.0 s to 3.0 s: {v_avg} km/s")

# Verification of velocity vector problem (with SymPy differentiation)

import numpy as np

import sympy as sp

def array_from_sympy(r, t, t_val):

temp = np.zeros(3)

for i in range(3):

temp[i] = float(r[i].subs(t, t_val))

return temp

# Symbolic variable

t = sp.Symbol('t', real=True)

# Symbolic position components (km)

x_t = 2.0*t**2

y_t = 2.0 + 3.0*t

z_t = 5.0*t

r_t = [x_t, y_t, z_t]

# Symbolic velocity components (km/s)

vx_t = sp.diff(x_t, t)

vy_t = sp.diff(y_t, t)

vz_t = sp.diff(z_t, t)

# Evaluate instantaneous velocity at t = 2.0 s

t_eval = 2.0

v_inst_sym = sp.Matrix([vx_t, vy_t, vz_t]).subs(t, t_eval)

v_inst = array_from_sympy([vx_t, vy_t, vz_t], t, t_eval)

speed = np.linalg.norm(v_inst)

# Average velocity from t1 to t2

t1 = 1.0

t2 = 3.0

r1 = array_from_sympy(r_t, t, t1)

r2 = array_from_sympy(r_t, t, t2)

v_avg = (r2 - r1) / (t2 - t1)

# Print results (formatted numerical output)

print(f"Instantaneous velocity at t = {t_eval:.1f} s: {v_inst} km/s")

print(f"Speed at t = {t_eval:.1f} s: {speed:.1f} km/s")

print(f"Average velocity from {t1:.1f} s to {t2:.1f} s: {v_avg} km/s")

Instantaneous velocity at t = 2.0 s: [8. 3. 5.] km/s

Speed at t = 2.0 s: 9.9 km/s

Average velocity from 1.0 s to 3.0 s: [8. 3. 5.] km/s

4.1.3. The Independence of Perpendicular Motions#

When we look at the 3D equations for position and velocity written in unit vector notation, we see the components are separate and unique functions of time that do not depend on each other.

Motion along the \(x\) direction has no part of its motion along the \(y\) or \(z\) directions.

Thus the motion of an object in 2D or 3D can be divided (separated) into independent motions along the perpendicular coordinate axes.

Consider a woman walking from point A to point B in a city with square blocks. The woman taking the path from A to B may walk east, then north for several blocks to arrive at point B. How far she walks east is affected only by her motion eastward (Recall the chessboard from Chapter 2).

Note

In kinematics, we can treat the horizontal and vertical components of motion separately. In many cases, motion in the horizontal direction does not affect the motion in the vertical direction and vice versa.

We can illustrate this with a stroboscope that captures the positions of two balls at fixed time intervals. One ball is dropped from rest and the other is thrown horizontally from the same height and follows a curved path (parabola).

Fig. 4.4 The red ball falls straight down, while the blue ball moves horizontally at constant speed while accelerating vertically. At equal time intervals, both objects have the same vertical position, as indicated by the dashed horizontal lines. The velocity and acceleration vectors illustrate that horizontal motion does not affect vertical motion. The animation was generated using Python, with AI-assisted code development (ChatGPT).#

Careful examination of the blue ball shows it travels the same horizontal distance between flashes. This is because there is only 1 force (gravity downward) acting on the ball after it is thrown. This means the horizontal velocity is constant. Note that in the real world, air resistance would affect the speed of the ball in both directions.

4.2. Acceleration Vector#

4.2.1. Instantaneous Acceleration#

The acceleration vector \(\vec{a}(t)\) is the instantaneous acceleration at any point in time along an object’s trajectory. It can be obtained in a similar way as was the velocity vector. Taking the derivative of \(\vec{\rm v}(t)\) with respect to time, we find

In terms of components we have the following form

4.2.1.1. Example Problem: Finding an Acceleration Vector#

Exercise 4.3

The Problem

A particle has a velocity of \(\vec{\rm v}(t) = 5.0t\ \hat{i} + t^2\ \hat{j} - 2.0t^3\ \hat{k}\ \text{km/s}.\) (a) What is the acceleration function? (b) What is the acceleration vector at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\)? Find its magnitude and direction.

The Model

The acceleration of a particle is defined as the time derivative of its velocity. Because the velocity is given in unit-vector form, the acceleration can be found by differentiating each component of the velocity function with respect to time.

Once the acceleration function is known, it can be evaluated at a specific time. The magnitude of the acceleration is then found using the Euclidean distance (norm) of the acceleration vector.

The Math

The acceleration function is the derivative of the velocity function,

Taking the derivative component-by-component gives

Evaluating the acceleration at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\),

The magnitude of the acceleration is

The Conclusion

The acceleration of the particle is time dependent and is given by

At \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\), the acceleration vector has a magnitude of \(24.8\ \text{km/s}^2\) and points in the direction \(5.0\ \hat{i} + 4.0\ \hat{j} - 24.0\ \hat{k}\). This example illustrates that acceleration can vary with time when the velocity function is nonlinear.

The Verification

In the verification step, the acceleration vector is represented as a NumPy array. This allows us to treat the components of the vector in the same way we would treat a vector written in unit-vector notation. Each element of the array corresponds to one Cartesian component of the acceleration.

The function np.linalg.norm computes the Euclidean norm of the array, which is the magnitude of the vector. For a vector with components \((a_x,\ a_y,\ a_z)\), this corresponds to the familiar expression

Using arrays in this way provides a direct numerical check of the analytical result and reinforces the connection between vector algebra and computational methods.

# Verification of acceleration vector

import numpy as np

t = 2.0

# Acceleration components (km/s^2)

a = np.array([5.0, 2.0*t, -6.0*t**2])

# Magnitude

a_mag = np.linalg.norm(a)

print(f"a(2.0 s) = {a} km/s^2")

print(f"|a(2.0 s)| = {a_mag:.1f} km/s^2")

4.2.1.2. Example Problem: Finding a Particle Acceleration#

Exercise 4.4

The Problem

A particle has a position function \(\vec{r}(t) = (10t - t^2)\ \hat{i} + 5t\ \hat{j} + 5t\ \hat{k}\ \text{m}.\) (a) What is the velocity? (b) What is the acceleration? (c) Describe the motion from \(t = 0\ \text{s}\).

The Model

Velocity is the first time derivative of the position function, and acceleration is the second time derivative. Because the position is linear in \(y\) and \(z\), the acceleration in those directions is zero. The motion in the \(x\) direction is quadratic in time, which implies a constant acceleration and a possible reversal in direction.

The Math

The velocity is obtained by differentiating the position function,

The acceleration is the derivative of the velocity,

The Conclusion

The particle moves with constant velocities in the \(y\) and \(z\) directions and a constant acceleration in the negative \(x\) direction. Initially, the particle moves in the positive \(x\) direction, but its velocity in \(x\) decreases linearly and becomes zero at \(t = 5\ \text{s}\). At this time, the particle reverses direction and accelerates back toward smaller \(x\) values. The particle reaches a maximum \(x\) position of \(25\ \text{m}\) and returns to \(x = 0\) at \(t = 10\ \text{s}\).

The Verification

To visualize the motion, we compute the particle’s position at evenly spaced times and plot the resulting trajectory in three dimensions. The plotted points represent the particle’s position at equal time intervals, allowing us to clearly see the turnaround in the \(x\) direction while motion in \(y\) and \(z\) continues steadily.

Note

A visualization using plotly is given below so that you can interact with the figure to see different perspectives. You are not expected to know to generate figures with plotly.

# Verification of particle motion from the position function

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Time array

t = np.linspace(0, 10, 15)

# Position components (m)

x = 10*t - t**2

y = 5*t

z = 5*t

# Create 3D plot

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6, 6), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

# Plot trajectory points

ax.scatter(x, y, z, color='tab:blue', s=40)

# Highlight the turnaround point at t = 5 s

t_turn = 5.0

x_turn = 10*t_turn - t_turn**2

y_turn = 5*t_turn

z_turn = 5*t_turn

ax.scatter(x_turn, y_turn, z_turn, color='tab:red', s=60)

# Axes labels

ax.set_xlabel("x (m)")

ax.set_ylabel("y (m)")

ax.set_zlabel("z (m)")

# Set limits for clarity

ax.set_xlim(0, 50)

ax.set_ylim(0, 50)

ax.set_zlim(0, 50)

ax.view_init(elev=25, azim=135)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Show code cell source

import numpy as np, plotly.graph_objects as go

from IPython.display import HTML

t=np.linspace(0,10,60); x=10*t-t**2; y=5*t; z=5*t; L=55; A=0.18*L

fig=go.Figure()

fig.add_trace(go.Scatter3d(x=x,y=y,z=z,mode='markers',name='',

marker=dict(size=7,color=t,colorscale='Viridis',opacity=0.9,showscale=True,

colorbar=dict(title="time (s)",thickness=18,len=0.9,x=1.03,tickfont=dict(size=14))),showlegend=False))

def axis_line(p,q): fig.add_trace(go.Scatter3d(x=[p[0],q[0]],y=[p[1],q[1]],z=[p[2],q[2]],mode='lines',

line=dict(color='black',width=6),hoverinfo='skip',showlegend=False,name=''))

def axis_tip(px,py,pz,ux,uy,uz): fig.add_trace(go.Cone(x=[px],y=[py],z=[pz],u=[ux],v=[uy],w=[uz],anchor='tip',

sizemode='absolute',sizeref=6,showscale=False,

colorscale=[[0,'black'],[1,'black']],hoverinfo='skip',showlegend=False,name=''))

def axis_label(px,py,pz,txt): fig.add_trace(go.Scatter3d(x=[px],y=[py],z=[pz],mode='text',text=[txt],

textfont=dict(size=16,color='black'),hoverinfo='skip',showlegend=False,name=''))

axis_line((-L,0,0),( L,0,0)); axis_line((0,-L,0),(0, L,0)); axis_line((0,0,-L),(0,0, L))

axis_tip( L,0,0, A,0,0); axis_tip(-L,0,0,-A,0,0); axis_tip(0, L,0,0, A,0); axis_tip(0,-L,0,0,-A,0); axis_tip(0,0, L,0,0, A); axis_tip(0,0,-L,0,0,-A)

axis_label( 1.12*L,0,0,"x"); axis_label(-1.12*L,0,0,"-x"); axis_label(0, 1.12*L,0,"y"); axis_label(0,-1.12*L,0,"-y"); axis_label(0,0, 1.12*L,"z"); axis_label(0,0,-1.12*L,"-z")

fig.update_layout(width=800, height=700,margin=dict(l=0,r=0,b=0,t=20),showlegend=False,

scene=dict(aspectmode='cube',

xaxis=dict(range=[-1.2*L,1.2*L],showbackground=False,showticklabels=False,showgrid=False,zeroline=False,title=''),

yaxis=dict(range=[-1.2*L,1.2*L],showbackground=False,showticklabels=False,showgrid=False,zeroline=False,title=''),

zaxis=dict(range=[-1.2*L,1.2*L],showbackground=False,showticklabels=False,showgrid=False,zeroline=False,title='')))

HTML(fig.to_html(full_html=False, include_plotlyjs="cdn"))

4.2.2. Constant Acceleration#

Constant acceleration in 2D or 3D can be treated the same way as in the previous chapter. To develop the relevant equations, let’s consider the 2D problem of a particle moving in the \(xy\) plane with constant acceleration. The acceleration vector \(\vec{a}\) is given as

Each of the kinematic equations for 1D motion now has component-forms that define the equation in the \(x\)- and \(y\)-directions. We can write the equations as

and

Here the subscript \(o\) refers initial value at \(t=0\). The position and velocity vectors in 2D are given as

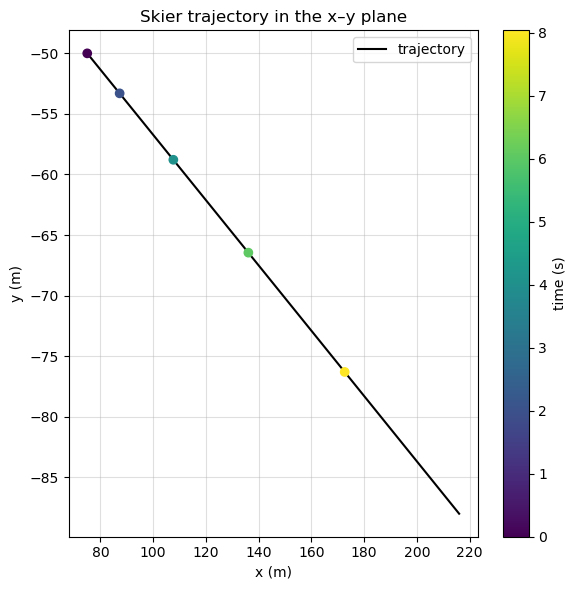

4.2.2.1. Example Problem: A Skier#

Exercise 4.5

The Problem

Figure 4.5 shows a skier moving with an acceleration of \(2.1\ \text{m/s}^2\) down a slope of \(15^\circ\) at \(t = 0\). With the origin of the coordinate system at the front of the lodge, her initial position and velocity are

\[\vec{r}(0) = (75.0\hat{i} - 50.0\hat{j})\ \text{m}\]and

\[\vec{\rm v}(0) = (4.1\hat{i} - 1.1\hat{j})\ \text{m/s}.\](a) What are the \(x\)- and \(y\)-components of the skier’s position and velocity as functions of time? (b) What are her position and velocity at \(t = 10.0\ \text{s}\)?

Fig. 4.5 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

We treat the skier’s motion as two-dimensional with constant acceleration. The acceleration has a fixed magnitude of \(2.1\ \text{m/s}^2\) directed \(15^\circ\) below the \(+x\) axis, so we first resolve it into components. Then we apply the constant-acceleration kinematic equations separately in the \(x\) and \(y\) directions.

The sign of each acceleration component is determined by the chosen coordinate system. The \(x\)-axis is taken to be horizontal and positive in the direction of motion down the slope, so the \(x\)-component of the acceleration is positive. The \(y\)-axis is defined to point vertically upward, while the skier accelerates downward along the slope. Therefore, the vertical component of the acceleration points in the negative \(y\) direction. Therefore, \(a_y\) carries a negative sign when the acceleration vector is resolved into components.

Common mistake

A frequent mistake is to assume the acceleration is negative simply because the skier is moving downhill. The sign of each component does not depend on whether the motion is “uphill” or “downhill,” but on how the coordinate axes are defined. In this problem, the \(y\)-axis points upward, so any downward component of acceleration must be negative, regardless of the direction of motion along the slope.

The Math

Because the skier accelerates down the slope at \(15^\circ\), the acceleration components are

(a) Component functions

Starting with the components from the initial vectors, the \(x\) motion has \(x_o = 75.0\ \text{m}\) and \(v_{xo} = 4.1\ \text{m/s}\), which gives

For the \(y\) motion with \(y_o = -50.0\ \text{m}\) and \(v_{yo} = -1.1\ \text{m/s}\),

(b) Values at \(t = 10.0\ \text{s}\)

Substituting \(t = 10.0\), we get:

and

So the position and velocity at \(t=10.0\ {\rm s}\) is,

The Conclusion

The skier’s component equations of motion are

and

At \(t = 10.0\ \text{s}\), her position and velocity are

This example shows that once the acceleration is resolved into components, the \(x\) and \(y\) motions can be solved independently using the same kinematic equations.

The Verification

We verify the result numerically by computing the acceleration components, building \(x(t)\) and \(y(t)\) from the kinematic equations, and evaluating the position and velocity at \(t = 10.0\ \text{s}\). The printed values match the analytical results.

# Verification of skier motion on an inclined slope

import numpy as np

# Given values

a = 2.1

theta = np.radians(15.0)

x0, y0 = 75.0, -50.0

vx0, vy0 = 4.1, -1.1

t = 10.0

# Acceleration components

ax = a*np.cos(theta)

ay = -a*np.sin(theta)

# Position and velocity at t

x = x0 + vx0*t + 0.5*ax*t**2

y = y0 + vy0*t + 0.5*ay*t**2

vx = vx0 + ax*t

vy = vy0 + ay*t

print(f"ax = {ax:.1f} m/s^2, ay = {ay:.2f} m/s^2")

print(f"r(10.0 s) = <{x:.1f}, {y:.1f}> m")

print(f"v(10.0 s) = <{vx:.1f}, {vy:.1f}> m/s")

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Time array

t = np.linspace(0, 10, 200)

# Motion equations

x = 75.0 + 4.1*t + 0.5*2.0*t**2

y = -50.0 - 1.1*t + 0.5*(-0.54)*t**2

# Plot trajectory

plt.figure(figsize=(6,6))

plt.plot(x, y, 'k-',lw=1.5,label="trajectory")

plt.scatter(x[::40], y[::40], c=t[::40], cmap="viridis", zorder=3)

plt.xlabel("x (m)")

plt.ylabel("y (m)")

plt.title("Skier trajectory in the x–y plane")

#plt.gca().invert_yaxis() # optional: downhill visually downward

plt.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

plt.colorbar(label="time (s)")

plt.legend()

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.2.3. Projectile Motion#

Projectile motion describes the motion of an object that is thrown or launched into the air, subject only to acceleration due to gravity. Some examples of projectile motion include

meteors entering Earth’s atmosphere,

fireworks,

cannonballs/bullets,

any ball in sports.

The launched/thrown object is called a projectile and its path is called a trajectory. We consider 2D projectile motion, which neglects the effects of air resistance.

In projectile motion problems, the motions along perpendicular axes are independent and thus can be analyzed separately. The key to analyzing such problems is to break (or separate) the problem into two motions: (a) along the horizontal axis and (b) along the vertical axis. By convention, we call the horizontal axis the \(x\)-axis and the vertical axis the \(y\)-axis.

We define a vector \(\vec{s}\) to describe the total displacement, while the vectors \(\vec{x}\) and \(\vec{y}\) are its component vectors along the respective axes. The magnitudes of these vectors are without arrows: \(s,\ x,\ \text{and}\ y\).

Fig. 4.6 Image Credit: Openstax#

Figure 4.6 illustrates these vectors with a soccer player kicking a ball.

How can we represent these vectors in unit vector notation?

They can be represented by

To describe the projectile motion completely, we must also include velocity and acceleration. Let’s assume that contact forces (e.g., air resistance and friction) are negligible. Defining the positive direction as upward, the components of acceleration are:

Because gravity is vertical, \(a_x = 0\) and \(v_x = v_{ox}\). We can then write the kinematic equations for motion in a uniform gravitational field as

Using this set of equations, we can analyze projectile motion. When the air resistance is negligible, the maximum height of the projectile is given by

where \(h = y-y_o\) and \(v_y = 0\). This equation defines the maximum height of a projectile above its launch position and it depends only on \(v_{oy}\).

Projectile Height (Calculus-framing)

Here we show how to find the maximum height from one of the kinematic equations. However, you can also think of this in terms of the \(y\) position equation using calculus. In calculus, you find the first derivative and set it equal to zero, or

which gives the time it takes to reach the maximum height. Then we substitute back into the position equation (and re-arrange to solve for \(h=y-y_o\)) to get

Problem Solving Strategy

Resolve the motion into \(x\) and \(y\) components, where the components of velocity \(\vec{\rm v}\) are \(v_x = v\cos{\theta}\) and \(v_y=v\sin{\theta}\). The magnitude of velocity is \(v\) and \(\theta\) is the direction relative to the \(x\) axis. See Fig. 4.7.

Treat the motion as 2 independent 1D motions: (a) one horizontal and (b) one vertical.

Solve for the unknowns in the two separate motions. Note that the only common variable between the motions is time \(t\).

Recombine quantities in the horizontal and vertical directions to find the total displacement \(\vec{s}\) and velocity \(\vec{\rm v}\). Solve for the magnitude and direction using

\[s = \sqrt{x^2+y^2}, \quad \Phi = \tan^{-1}\left(\frac{y}{x}\right), \quad v = \sqrt{v_x^2 + v_y^2}, \]

where \(\Phi\) is the direction of \(\vec{s}\).

Fig. 4.7 Image Credit: Openstax#

4.2.3.1. Example Problem: A Fireworks Projectile Explodes#

Exercise 4.6

The Problem

During a fireworks display, a shell is shot into the air with an initial speed of \(70.0\ \text{m/s}\) at an angle of \(75.0^\circ\) above the horizontal, as illustrated in Figure 4.8. The fuse is timed to ignite the shell just as it reaches its highest point above the ground. (a) Calculate the height at which the shell explodes. (b) How much time passes between the launch of the shell and the explosion? (c) What is the horizontal displacement of the shell when it explodes? (d) What is the total displacement from the point of launch to the highest point?

Fig. 4.8 Image Credit: Openstax#

The Model

We model the shell as a projectile moving in two dimensions under constant acceleration due to gravity. Air resistance is neglected, so the horizontal acceleration is zero and the vertical acceleration is constant and downward with magnitude \(g = 9.80\ \text{m/s}^2\). The motion is analyzed by resolving the initial velocity into horizontal and vertical components and applying the kinematic equations independently in each direction.

At the highest point of the trajectory (the apex), the vertical component of the velocity is zero. This condition allows us to determine the time and height of the explosion directly from the vertical motion.

The Math

The initial velocity components are

with \(v_o = 70.0\ \text{m/s}\) and \(\theta_o = 75.0^\circ\). Evaluating,

(a) Maximum height

The vertical velocity at the apex is zero, so we use

Taking \(y_o = 0\) and \(v_y = 0\) gives

or

Substituting values,

(b) Time to reach the highest point

At the apex, \(v_y = 0\), so from

we have

which gives

(c) Horizontal displacement at the explosion

The horizontal velocity is constant because \(a_x = 0\). Thus,

Using the time found above,

(d) Total displacement to the highest point

The displacement vector from the launch point to the apex is

Its magnitude is

and its direction relative to the horizontal is

The Conclusion

The shell explodes at a height of \(233\ \text{m}\) after \(6.90\ \text{s}\) of flight. At that moment it is \(125\ \text{m}\) horizontally from the launch point. The total displacement from launch to the highest point has a magnitude of \(264\ \text{m}\) and is directed \(61.8^\circ\) above the horizontal.

This example highlights that the maximum height depends only on the vertical component of the initial velocity, while the horizontal displacement depends on the horizontal component and the time of flight.

The Verification

We can verify these results numerically by computing the velocity components, evaluating the kinematic equations at the time when \(v_y = 0\), and comparing the resulting height and displacement with the analytical values.

# Verification of fireworks projectile motion

import numpy as np

v0 = 70.0

theta = np.radians(75.0)

g = 9.80

v0x = v0*np.cos(theta)

v0y = v0*np.sin(theta)

t = v0y/g

y = v0y**2/(2*g)

x = v0x*t

s = np.sqrt(x**2 + y**2)

phi = np.degrees(np.arctan2(y,x))

print(f"Time to apex = {t:.2f} s")

print(f"Height = {y:.0f} m")

print(f"Horizontal displacement = {x:.0f} m")

print(f"|s| = {s:.0f} m at {phi:.1f} degrees")

4.2.3.2. Example Problem: The Tennis Player#

Exercise 4.7

The Problem

A tennis player wins a match at Arthur Ashe Stadium and hits a ball into the stands at \(30\ \text{m/s}\) and at an angle \(45^\circ\) above the horizontal. On its way down, the ball is caught by a spectator \(10\ \text{m}\) above the point where the ball was hit. (a) Calculate the time it takes the tennis ball to reach the spectator. (b) What are the magnitude and direction of the ball’s velocity at impact?

The Model

The tennis ball is modeled as an ideal projectile. Air resistance is neglected, the motion takes place near Earth’s surface, and the only acceleration is due to gravity. The horizontal and vertical motions are independent, with constant horizontal velocity and constant downward acceleration. The time of flight to a given height is determined entirely by the vertical motion, while the velocity at impact is found by recombining the horizontal and vertical components at that time.

The Math

We take upward to be the positive \(y\) direction and choose the launch point as \(y_o = 0\). The acceleration due to gravity is \(g = 9.81\ \text{m/s}^2\).

The initial speed is \(v_o = 30\ \text{m/s}\) at an angle \(\theta_o = 45^\circ\), so the initial velocity components are

Substituting the numerical values gives

(a) Time to reach the spectator

The vertical position as a function of time is

At the spectator’s location, \(y = 10\ \text{m}\), so

Solving this quadratic equation gives two solutions. The smaller time corresponds to the ball passing through \(y=10\ \text{m}\) on the way up, while the larger time corresponds to the ball being caught on the way down. The physically relevant solution is

(b) Velocity at impact

The horizontal velocity remains constant throughout the motion,

The vertical velocity at time \(t\) is

Evaluating this at \(t = 3.8\ \text{s}\),

The magnitude of the velocity at impact is

The direction of the velocity relative to the horizontal is

directed below the horizontal.

The Conclusion

The tennis ball reaches the spectator \(3.8\ \text{s}\) after being hit. At impact, the ball’s speed is \(27\ \text{m/s}\) and its velocity is directed \(37^\circ\) below the horizontal. Although the ball was launched upward, the negative vertical component of the velocity at impact reflects the fact that the ball is descending when it is caught. The smaller speed compared to the launch speed is consistent with the ball being caught at a height above the launch point.

The Verification

We verify the results by solving the vertical motion numerically, computing the velocity components at the impact time, and producing a minimal sketch of the trajectory.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

v0 = 30.0

theta = 45.0*np.pi/180

g = 9.81

v0x = v0*np.cos(theta)

v0y = v0*np.sin(theta)

# Solve quadratic for y = 10 m

coeff = [0.5*g, -v0y, 10.0]

t_roots = np.roots(coeff)

t = np.max(t_roots) # time on the way down

vx = v0x

vy = v0y - g*t

v = np.sqrt(vx**2 + vy**2)

print(f"time = {t:.2f} s")

print(f"vx = {vx:.1f} m/s, vy = {vy:.1f} m/s")

print(f"speed = {v:.1f} m/s")

# Minimal sketch

t_plot = np.linspace(0, t, 300)

x = v0x*t_plot

y = v0y*t_plot - 0.5*g*t_plot**2

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(6,4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(x, y, 'k')

ax.plot(x[-1], y[-1], 'ro')

ax.set_xlabel("x (m)")

ax.set_ylabel("y (m)")

ax.set_title("Projectile trajectory to the spectator")

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.2.4. Time of Flight, Trajectory, and Range#

4.2.4.1. Time of Flight#

The duration of time the projectile spends from the launch time to the impact time is called the time of flight \(T_{\rm tof}\). We note the position and displacement in \(y\) must be zero at launch and at impact on an even surface. Thus, we set the displacement \(y-y_o = 0\) and find

We can solve for \(t\) and set it equal to the time of flight \(t=T_{\rm tof}\) to get

Note

The above equation does not apply when the projectile lands at a different elevation than it was launched.

The other solution \(t=0\) corresponds to the launch time. The time of flight is linearly proportional to the initial velocity \(v_{oy}\) and inversely proportional to \(g\). On the Moon the value of \(g_{\rm Moon}\) is \({\sim}1/6\) that of \(g_{\rm Earth}\). Therefore, the time of flight \(T_{\rm tof}^{\rm Moon}\) on the Moon is about \(6\times\) longer than the equivalent \(T_{\rm tof}^{\rm Earth}\) with the same launch velocity \(v_{oy}\), or

4.2.4.2. Trajectory#

A particle’s trajectory can be found by substituting the \(t\) from the \(x\) kinematic equation into the \(y\) kinematic equation for position, thereby eliminating the \(t\) altogether. If we take the initial position as the origin (\(x_o,\ y_o = 0,\ 0\)). The kinematic equation for \(x\) gives

Then, we substitute into equation for the \(y\) position

Rearranging terms, we have

This trajectory equation is an equation of a parabola (\(y = c + bx + ax^2\)) with coefficients

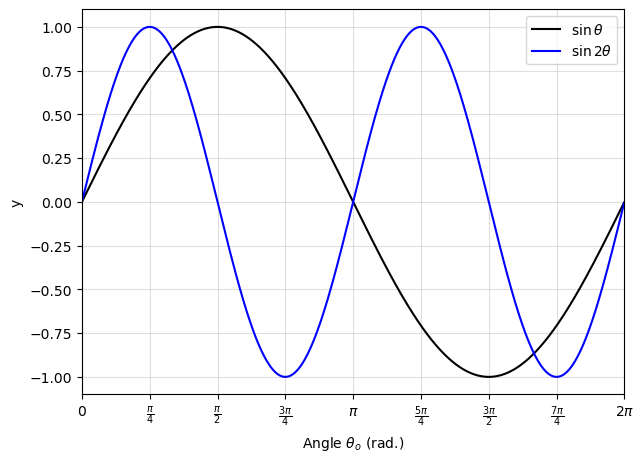

4.2.4.3. Range#

From the trajectory equation, we can also find the range, or the horizontal distance traveled by a projectile. Factoring \(x\), we have

The position \(y\) is zero for both the launch and impact point, since we are considering only a flat horizontal surface. Finding the root of the term in brackets (using algebra), we get

Using the trig identity \(\sin{2\theta_o} (= 2\sin{\theta_o}\cos{\theta_o})\) and setting \(x=R\) for range, we find

The range is directly proportional to the square of the initial speed \(v_o\), the launch angle through \(\sin{2\theta_o}\), and inversely proportional to the acceleration due to gravity \(g\).

Projectile Range (Calculus-framing)

Here we show how to find the maximum range from one of the kinematic equations. However, you can also think of this in terms of the position equations using calculus. In calculus, you find the first derivative and set it equal to zero, or

which gives the time it takes to reach the maximum height. Since the motions are independent, we can say that \(2t\) is the time to go up and come back down. Note that this is the same as the time of flight.

Then we substitute back into the \(x\) position equation (and re-arrange to solve for \(R=x-x_o\)) to get

where we used the trig identity \(\sin{2\theta_o} (= 2\sin{\theta_o}\cos{\theta_o})\).

See the python code below and the figure illustrating the differences between \(\sin{\theta}\) and \(\sin{2\theta}\). This shows that there is positive maxima for \(\sin{2\theta}\), which does not occur at \(\pi/2\) (or \(90^\circ\)).

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from fractions import Fraction

theta = np.arange(0, 2*np.pi, 0.01)

y1 = np.sin(theta)

y2 = np.sin(2*theta)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7,5), dpi=100)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

ax.plot(theta, y1, 'k-', lw=1.5, label=r'$\sin\theta$')

ax.plot(theta, y2, 'b-', lw=1.5, label=r'$\sin 2\theta$')

# Set ticks every pi/4

xticks = np.arange(0, 2*np.pi + np.pi/4, np.pi/4)

ax.set_xlim(0, 2*np.pi)

ax.set_xticks(xticks)

# Generate reduced pi-fraction labels

xtick_labels = []

for x in xticks:

frac = Fraction(x/np.pi).limit_denominator()

if frac == 0:

label = r"$0$"

elif frac.denominator == 1:

# Integer multiples of pi

if frac.numerator == 1:

label = r"$\pi$"

else:

label = rf"${frac.numerator}\pi$"

else:

# Proper fractions

if frac.numerator == 1:

label = rf"$\frac{{\pi}}{{{frac.denominator}}}$"

else:

label = rf"$\frac{{{frac.numerator}\pi}}{{{frac.denominator}}}$"

xtick_labels.append(label)

ax.set_xticklabels(xtick_labels)

ax.set_xlabel("Angle $\\theta_o$ (rad.)")

ax.set_ylabel("y")

ax.legend(loc='best')

plt.show()

What will be the range for a projectile on the Moon?

The range would be \(6\times\) greater due to the inverse proportionality to \(g\). Recall the example with the time-of-flight on the Moon.

At what angle \(\theta_o\) will the range be maximized?

We can see from the above Python figure that the \(\sin{2\theta}\) will be first maximized at \(\theta_o = \pi/4\) (or \(45^\circ\)), where a second maximum occurs at \(\theta_o = 5\pi/4\) (or \(225^\circ\)). However, we ignore the second maximum because it is pointed behind the launch point and below the horizon!

Maximum Angle (Calculus-framing)

We want to identify the angle \(\theta_o\), where the range is maximized. Using the same procedure as other maximization problems, we find the derivative and set it equal to zero. In this case, we have

We use the points where \(\cos{2\theta_o} = 0\) to maximize the range, which results in

where we take only the first integer \(n=1\) to get

We have neglected air resistance, where the maximum angle is somewhat smaller if it is considered (see Figure 4.9). Notice that (in the case of air resistance), there can be two angles with the same range but different maximum heights.

Fig. 4.9 Image Credit: Openstax#

Interactive Simulation: Hydrogen Atom Models

Use this PHET simulation to explore projectile motion in terms of the launch angle and initial velocity. Adjust parameters and observe how predicted projectile range and height differs between models.

Exercise 4.8

The Problem

A golfer encounters two different situations on different holes. On the second hole they are 120 m from the green and want to hit the ball 90 m and let it run onto the green. They angle the shot low to the ground at \(30^\circ\) to the horizontal to let the ball roll after impact. On the fourth hole they are 90 m from the green and want to let the ball drop with a minimum amount of rolling after impact. Here, they angle the shot at \(70^\circ\) to the horizontal to minimize rolling after impact. Both shots are hit and impacted on a level surface.

(a) What is the initial speed of the ball at the second hole?

(b) What is the initial speed of the ball at the fourth hole?

(c) Write the trajectory equation for both cases.

(d) Graph the trajectories.

The Model

Each golf shot is modeled as ideal projectile motion. The ball is launched and lands at the same height on level ground, air resistance is neglected, and the only acceleration is gravity. Under these assumptions, the horizontal range depends on the launch speed and angle through the factor \(\sin(2\theta_o)\), and the path of the ball can be written as a quadratic function of \(x\).

The Math

We use \(g = 9.81\ \text{m/s}^2\) and the measured range \(R = 90\ \text{m}\), which limits the final numerical results to two significant figures.

For projectile motion on level ground, the range is

Solving for the launch speed,

For the second hole (b) with \(\theta_o = 30^\circ\),

For the fourth hole (d) with \(\theta_o = 70^\circ\),

To write the trajectory (c), we use the projectile path equation

For the \(30^\circ\) shot,

For the \(70^\circ\) shot,

The Conclusion

To carry the ball \(90\ \text{m}\) on level ground, the golfer must launch it at \(32\ \text{m/s}\) for a \(30^\circ\) shot and at \(37\ \text{m/s}\) for a \(70^\circ\) shot. Even though both shots have the same range, the high-angle shot requires a larger launch speed because \(\sin(2\theta_o)\) is smaller at \(70^\circ\) than it is at \(30^\circ\).

The Verification

We verify the results numerically (d) by computing the launch speeds from the range equation, generating the two trajectories, and confirming that both satisfy \(y(90\ \text{m}) \approx 0\).

# Verification of golf shot trajectories

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

g = 9.81

R = 90.0

theta1 = np.radians(30.0)

theta2 = np.radians(70.0)

v01 = np.sqrt(R*g/np.sin(2*theta1))

v02 = np.sqrt(R*g/np.sin(2*theta2))

x = np.linspace(0, R, 400)

y1 = x*np.tan(theta1) - g*x**2/(2*(v01*np.cos(theta1))**2)

y2 = x*np.tan(theta2) - g*x**2/(2*(v02*np.cos(theta2))**2)

print(f"Second hole: v0 = {v01:.0f} m/s")

print(f"Fourth hole: v0 = {v02:.0f} m/s")

print(f"y1(R) = {y1[-1]:.3f} m, y2(R) = {y2[-1]:.3f} m")

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(7,5), dpi=100)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

ax.plot(x, y1, 'k-', lw=1.5, label=r"$30^\circ$ shot")

ax.plot(x, y2, 'b-', lw=1.5, label=r"$70^\circ$ shot")

ax.set_xlabel("x (m)")

ax.set_ylabel("y (m)")

ax.set_xlim(0, 90)

ax.set_ylim(bottom=0)

ax.legend(loc="best")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.3. Uniform and Nonuniform Circular Motion#

Uniform circular motion describes an object that travels in circle with a constant speed. For example, any point on a propeller spinning at a constant rate is undergoing uniform circular motion, or a point on the edge of a spinning disk. Points on these rotating objects are actually accelerating (i.e., changing direction), although the rotation rate is a constant.

4.3.1. Centripetal Acceleration#

In 1D kinematics, objects with a constant speed have zero acceleration. However, in 2D and 3D kinematics, a particle can have acceleration if it moves along a curved trajectory (e.g., a circle) with a constant speed.

In this case, the velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}\) is changing, or \(d\vec{\rm v}{dt} \neq 0\). As a particle moves counterclockwise in time through an interval \(\Delta t\) on a circular path,

its position vector moves from \(\vec{r}(t)\) to \(\vec{r}(t+\Delta t)\).

its velocity vector has a constant magnitude \(v\) and is tangent to the path as it changes from \(\vec{\rm v}(t)\) to \(\vec{\rm v}(t+\Delta t)\), only changing its direction.

Since the velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}(t)\) is perpendicular to the position vector \(\vec{r}(t)\), the triangles formed by the position vectors along with its difference vector \(\Delta \vec{r}\) and the velocity vector \(\vec{\rm v}\) along with its difference vector \(\Delta \vec{\rm v}\) are similar. Furthermore, the two triangles are isosceles. From these facts we have

We can find the magnitude of the acceleration from

A particle moving in a circle at a constant speed has an acceleration with magnitude

The direction of the acceleration vector is pointed inwards, toward the center of the circle. This is a radial acceleration because its along the radial direction, and is also called the centripetal acceleration.

Note

The word centripetal comes from the Latin words centrum (meaning “center”) and petere (meaning “to seek”), and thus takes the meaning “center seeking.”

Centripetal acceleration can have a wide range of values, depending on the speed and radius of the circular path. Typical centripetal acceleration values are given in the following table.

Object |

Centripetal Acceleration |

|---|---|

Moon around the Earth |

\(2.8\times10^{-4}\) |

Earth around the Sun |

\(6.1\times10^{-4}\) |

Satellite in geosynchronous orbit |

\(2.4\times10^{-2}\) |

Outer edge of a CD when playing |

\(0.59\) |

Jet in a barrel roll |

\(2\)–\(3\) |

Roller coaster |

\(5\) |

Electron orbiting a proton (Bohr model) |

\(9.2\times10^{21}\) |

4.3.1.1. Example Problem: Creating an Acceleration of 1 \(g\)#

Exercise 4.9

The Problem

A jet is flying at a speed of \(134.1\ \text{m/s}\) along a straight line and then makes a turn along a circular path that is level with the ground. What does the radius of the circular path have to be to produce a centripetal acceleration of \(1\,g\) on the pilot and jet toward the center of the circular trajectory?

The Model

The jet is modeled as moving at constant speed along a horizontal circular path. Because the speed remains constant, the acceleration of the jet is purely centripetal and always directed toward the center of the circular path. The magnitude of this acceleration depends only on the jet’s speed and the radius of the turn. Changes in altitude and air resistance are neglected.

The Math

For uniform circular motion, the magnitude of the centripetal acceleration is given by

In this problem, the centripetal acceleration is specified to be equal to the acceleration due to gravity, so we set

Solving for the radius of the circular path gives

Substituting the given speed and taking \(g = 9.81\ \text{m/s}^2\),

Evaluating this expression yields

which can also be written as

The Conclusion

To produce a centripetal acceleration of \(1\,g\) while flying at a speed of \(134.1\ \text{m/s}\), the jet must follow a circular path with a radius of approximately \(1.83\ \text{km}\).

This result highlights an important physical idea: at high speeds, even modest accelerations require very large turning radii. A sustained turn that produces only \(1\,g\) spans several kilometers, comparable to the size of a small city. To increase the centripetal acceleration beyond \(1\ g\), the jet would need to fly faster, turn more sharply, or both. This constraint explains why high-speed aircraft require large airspace when performing sustained maneuvers.

The Verification

We can verify the analytical result by directly computing the radius from the centripetal acceleration formula using Python.

# Verification of centripetal acceleration calculation

v = 134.1 # m/s

g = 9.81 # m/s^2

r = v**2 / g

print(f"Turning radius = {r:.0f} m")

print(f"Turning radius = {r/1000:.2f} km")

4.3.2. Equations of Motion for Uniform Circular Motion#

A particle undergoing circular motion can be described using its position vector \(\vec{r}\). As the particle moves on the circle, its position vector sweeps out the angle \(\theta\) (measured relative to the \(+\hat{i}\) direction). The vector \(\vec{r}(t)\) can be represented in terms of its components by

where \(\omega\) represents the angular frequency in units of \(\rm rad/s\). Like the change in position for 1D motion, the change in angle is represented in a similar way,

If \(T\) is the time to complete a single revolution (or orbital period), then

Velocity and acceleration can be found by differentiation of the position function, or

From these equations, we see that the magnitude of the velocity is \(A\omega\) and the magnitude of the acceleration is \(A\omega^2\). The acceleration can be written simply as \(\vec{a} = -\omega^2\vec{r}\).

4.3.2.1. Example Problem: Circular Motion of a Proton#

Exercise 4.10

The Problem

A proton has speed \(5.0\times10^6\ \text{m/s}\) and is moving in a circle in the \(xy\) plane of radius \(r = 0.175\ \text{m}\). What is its position in the \(xy\) plane at time \(t = 2.0\times10^{-7}\ \text{s} = 200\ \text{ns}\)? At \(t = 0\), the position of the proton is \(0.175,\hat{i}\ \text{m}\) and it circles counterclockwise. Sketch the trajectory.

The Model

The proton undergoes uniform circular motion in the \(xy\) plane. Its speed is constant, while the direction of its velocity changes continuously, producing a centripetal acceleration toward the center of the circle.

For counterclockwise circular motion that begins on the positive \(x\)-axis, the position of the particle can be written as

The angular frequency \(\omega\) is related to the speed and radius through

The Math

Using the given speed and radius, the angular frequency is

The position of the proton at time \(t\) is therefore

Evaluating this expression at \(t = 2.0\times10^{-7}\ \text{s}\),

Substituting into the position vector gives

The Conclusion

After \(200\ \text{ns}\), the proton is located at

This position lies slightly below the \(x\)-axis and to the right of the origin, consistent with counterclockwise circular motion that has carried the proton through a little less than one full revolution.

The Verification

We verify the analytical result numerically by computing the angular frequency, evaluating the position at \(t = 200\ \text{ns}\), and producing a minimal sketch of the circular trajectory.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

r = 0.175

v = 5.0e6

t = 2.0e-7

# Angular frequency

omega = v / r

# Position at time t

x = r * np.cos(omega * t)

y = r * np.sin(omega * t)

print(f"x = {x:.2f} m")

print(f"y = {y:.2f} m")

# Minimal trajectory sketch

theta = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 400)

xc = r * np.cos(theta)

yc = r * np.sin(theta)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,5), dpi=100)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(xc, yc, 'k--', lw=1, label="Trajectory")

ax.plot(x, y, 'ro', label="Position at 200 ns")

ax.plot(r, 0, 'bo', label="Initial position")

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.set_xlabel("x (m)")

ax.set_ylabel("y (m)")

ax.grid(True, alpha=0.4)

ax.legend(loc="best")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.3.3. Nonuniform Circular Motion#

Circular motion does not have to be at a constant speed, where a particle can accelerate in the normal fashion (e.g., speed up or slow down).

If the particle is changing speed (as well as with direction), then we introduce another acceleration in the direction tangential to the circle (i.e., transverse acceleration). The centripetal acceleration is the time rate of change of the direction of the velocity vector, where the tangential acceleration \(a_T\) is the time rate of change of the magnitude of the velocity vector. This is given by

The direction of the tangential acceleration is tangent to the circle, where the centripetal acceleration is radially inward toward the center. Thus the two vectors are components of the total acceleration vector \(\vec{a}\), or

Note that the component vectors are perpendicular to each other like how the Cartesian unit vectors are also perpendicular to each other.

4.3.3.1. Example Problem: Total Acceleration during Circular Motion#

Exercise 4.11

The Problem

A particle moves in a circle of radius \(r = 2.0\ \text{m}\). During the time interval from \(t = 1.5\ \text{s}\) to \(t = 4.0\ \text{s}\) its speed varies with time according to

\[v(t) = c_1 - \dfrac{c_2}{t^2}, \quad c_1 = 4.0\ \text{m/s} ; c_2 = 6.0\ \text{m}\cdot\text{s}.\]What is the total acceleration of the particle at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\)?

The Model

The particle undergoes nonuniform circular motion. Its acceleration has two perpendicular components: a centripetal component directed toward the center of the circle and a tangential component along the direction of motion. The centripetal acceleration depends on the instantaneous speed and radius, while the tangential acceleration depends on how the speed changes with time. The total acceleration is the vector sum of these two components.

The Math

We first evaluate the speed at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\) using the given function,

The centripetal acceleration at this instant is

directed radially inward.

The tangential acceleration is found from the time derivative of the speed. Differentiating \(v(t) = 4.0 - 6.0 t^{-2}\) gives

Evaluating at \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\),

directed along the tangent to the circular path.

Because the centripetal and tangential accelerations are perpendicular, the magnitude of the total acceleration is

The direction of the total acceleration relative to the tangential direction is

measured inward from the tangent toward the center of the circle.

The Conclusion

At \(t = 2.0\ \text{s}\), the particle has a centripetal acceleration of \(3.1\ \text{m/s}^2\) toward the center and a tangential acceleration of \(1.5\ \text{m/s}^2\) along the direction of motion. The resulting total acceleration has magnitude \(3.4\ \text{m/s}^2\) and points \(64^\circ\) inward from the tangent. This result illustrates how changes in speed and changes in direction combine to determine the acceleration in nonuniform circular motion.

The Verification

We verify the result numerically by evaluating the speed, centripetal acceleration, tangential acceleration, and total acceleration directly, and by producing a minimal sketch showing the geometry of the acceleration components.

# Verification of nonuniform circular motion

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Given values

r = 2.0

c1 = 4.0

c2 = 6.0

t = 2.0

# Speed and accelerations

v = c1 - c2/t**2

a_c = v**2 / r

a_T = 12.0 / t**3

a_tot = np.sqrt(a_c**2 + a_T**2)

print(f"v(2.0 s) = {v:.2f} m/s")

print(f"a_c = {a_c:.2f} m/s^2")

print(f"a_T = {a_T:.2f} m/s^2")

print(f"|a| = {a_tot:.2f} m/s^2")

# Minimal sketch

theta = np.linspace(0, 2*np.pi, 400)

x = r*np.cos(theta)

y = r*np.sin(theta)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,5), dpi=100)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.plot(x, y, 'k-', lw=1)

# Particle location at rightmost point

ax.plot([r], [0], 'ko')

# Acceleration vectors

ax.arrow(r, 0, -a_c/5, 0, head_width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, color='C0')

ax.arrow(r, 0, 0, a_T/5, head_width=0.05, length_includes_head=True, color='C1')

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_title("Centripetal (inward) and Tangential (upward) Accelerations")

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

4.4. Relative Motion in One and Two Dimensions#

4.4.1. Reference Frames#

Motion is measured relative to a reference, where this is often relative to the ground (i.e., the reference). Suppose that you’re riding a train moving east and pass another train also moving east, then your velocity relative to the other train is different than your velocity relative to the ground.

The reference frame is an explicit statement describing the reference of the relative motion in one or more dimensions. We can expand our view of moving on a train to how the Earth spins or moves around the Sun because it is moving too. When considering the Earth’s motion around the Sun, then the Solar System is the reference frame.

Note

The Solar System is a proper noun and should be captialized. There is not more than one “Solar System”, where planets orbiting other stars are called exoplanets. Multiple planets orbiting the same star is a multiple-planetary system (or multi).

The Solar System for an astronomer or planetary scientist carries a specific meaning like how “theory” has a specific meaning in science compared to lay-usage. This usually means that a planetary system is similar in one specific way to our Solar System.

Reference frames were applied more widely after Galileo developed his mechanics because he was trying to explain why the Earth could spin and go around the Sun. The methods outlined in this section are applicable following Galileo and breakdown once the object moves closer to the speed of light. The slow-moving (relative to lightspeed) regime is also called Galilean transformations. The fast-moving (close to lightspeed) regime is called a Lorentz transformation and is used when studying problems in Einstein’s special theory of relativity.

4.4.2. Relative Motion in 1D#

In 1D, the velocity vectors only have two possible directions (e.g., east/west, left/right, positive/negative). Take the example of a person sitting in a train that is moving east, where east is the positive direction and Earth is the reference frame.

Then, we can write down the velocity of the train with respect to the Earth as

where the subscript \(TE\) denotes the train’s velocity is measured relative to the Earth.

A person gets up and walks toward the back of the train at \(2\ {\rm m/s}\). Since the train is moving east, the person must be moving west towards the back of the train. We can write the velocity of the person as

We can add these two vectors together to find the velocity of the person with respect to the Earth (i.e., \(PE\)). This relative velocity is written as

Note

The ordering of the subscripts is chosen so the intermediate frame lies in the middle of the vector addition. As a result, the final vector contains the remaining subscripts. Figure 4.10 shows this coupling.

Fig. 4.10 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

Adding the vectors, we find

So the person is moving \(8\ {\rm m/s}\) east with respect to the Earth.

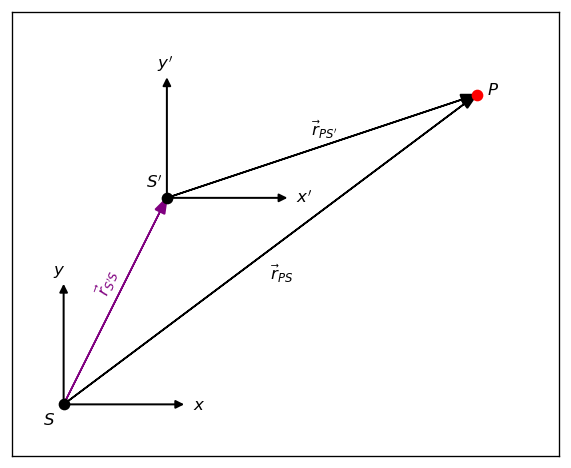

4.4.3. Relative Velocity in 2D#

We can now apply these concepts to 2D considering a particle \(P\) and reference frames \(S\) and \(S^\prime\) (see Fig. 4.11). The position of the origin \(S^\prime\) as measured in \(S\) is \(\vec{r}_{S^\prime S}\), where the position \(P\) measured in \(S^\prime\) is \(\vec{r}_{PS^\prime}\) and the position of \(P\) as measured in \(S\) is \(\vec{r}_{PS}\).

Fig. 4.11 A 2D displacement-vector diagram showing \(\vec{r}_{PS}\), \(\vec{r}_{PS'}\), and \(\vec{r}_{S'S}\).#

From Fig. 4.11 we see that the relative positions and velocities are given by

We can extend this method of vector addition to any number of reference frames. For particle \(P\), its velocity can be computed relative to frames \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) as

We can also see how the accelerations are related in two reference frames by differentiating to get

Suppose that the velocity of \(S^\prime\) relative to \(S\) is a constant, then \(\vec{a}_{S^\prime S} = 0\) and

which means that the acceleration of a particle is the same as measured by two observers moving at a constant velocity relative to each other.

Show code cell content

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

from myst_nb import glue

# Define points in 2D

S = np.array([0.0, 0.0])

Sp = np.array([1.0, 2.0])

P = np.array([4.0, 3.0])

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,4), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

# Draw vectors

ax.arrow(S[0], S[1], Sp[0]-S[0], Sp[1]-S[1],

length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.1, color='purple')

ax.arrow(Sp[0], Sp[1], P[0]-Sp[0], P[1]-Sp[1],

length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.1, color='black')

ax.arrow(S[0], S[1], P[0]-S[0], P[1]-S[1],

length_includes_head=True, head_width=0.1, color='black')

# Mark points

ax.plot(*S, 'ko')

ax.plot(*Sp, 'ko')

ax.plot(*P, 'ro')

# --- Draw coordinate axes (x,y) at S and (x',y') at S' ---

axis_len = 1.2

axis_lw = 1.2

axis_head = 10 # arrowhead size (points)

# Unprimed axes at S

ax.annotate("", xy=(S[0] + axis_len, S[1]), xytext=(S[0], S[1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="-|>", lw=axis_lw, color="black", mutation_scale=axis_head))

ax.annotate("", xy=(S[0], S[1] + axis_len), xytext=(S[0], S[1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="-|>", lw=axis_lw, color="black", mutation_scale=axis_head))

ax.text(S[0] + axis_len + 0.05, S[1] - 0.05, r"$x$")

ax.text(S[0] - 0.10, S[1] + axis_len + 0.05, r"$y$")

# Primed axes at S' (same orientation here; rotate if you want later)

ax.annotate("", xy=(Sp[0] + axis_len, Sp[1]), xytext=(Sp[0], Sp[1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="-|>", lw=axis_lw, color="black", mutation_scale=axis_head))

ax.annotate("", xy=(Sp[0], Sp[1] + axis_len), xytext=(Sp[0], Sp[1]),

arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="-|>", lw=axis_lw, color="black", mutation_scale=axis_head))

ax.text(Sp[0] + axis_len + 0.05, Sp[1] - 0.05, r"$x'$")

ax.text(Sp[0] - 0.10, Sp[1] + axis_len + 0.05, r"$y'$")

# Labels

ax.text(S[0]-0.2, S[1]-0.2, r"$S$")

ax.text(Sp[0]-0.2, Sp[1]+0.1, r"$S'$")

ax.text(P[0]+0.1, P[1], r"$P$")

ax.text(0.28, 1.07, r"$\vec{r}_{S'S}$", color='purple',rotation=70)

ax.text(2.4, 2.6, r"$\vec{r}_{PS'}$")

ax.text(2.0, 1.2, r"$\vec{r}_{PS}$")

ax.set_aspect("equal")

ax.set_xticks([])

ax.set_yticks([])

ax.set_xlim(-0.5, 4.8)

ax.set_ylim(-0.5, 3.8)

plt.tight_layout()

glue("vector_2D_diagram", fig, display=False)

plt.show()

4.4.3.1. Example Problem: Motion of a Car Relative to a Truck#

Exercise 4.12

The Problem

A truck is traveling south at a speed of \(70\ \text{km/h}\) toward an intersection. A car is traveling east toward the intersection at a speed of \(80\ \text{km/h}\). What is the velocity of the car relative to the truck?

The Model

We describe the motion using a common inertial reference frame: Earth. Velocities are treated as vectors in a two-dimensional \(x\)–\(y\) coordinate system, with \(\hat{i}\) pointing east and \(\hat{j}\) pointing north. The relative velocity of one object with respect to another is found by vector addition, using Earth as the connecting reference frame.

The Math

The velocity of the car with respect to Earth is purely eastward,

The truck is traveling south, which corresponds to the negative \(y\)-direction,

The velocity of the car relative to the truck is obtained from the relative velocity relation

Substituting the known vectors gives

The magnitude of the relative velocity is

The direction, measured north of east, follows from

The Conclusion

The car moves relative to the truck with a speed of \(110\ \text{km/h}\) at an angle of \(41^\circ\) north of east. This result reflects the fact that, from the truck’s point of view, the car is simultaneously moving eastward and northward. Relative motion problems reduce to careful bookkeeping of vector directions and reference frames.

The Verification

We verify the result numerically by constructing the velocity vectors as arrays and computing the magnitude and direction using standard vector operations.

# Verification of relative velocity

import numpy as np

# Velocity vectors (km/h)

v_CE = np.array([80.0, 0.0]) # car relative to Earth

v_TE = np.array([0.0, 70.0]) # truck relative to Earth

# Relative velocity of car with respect to truck

v_ET = -v_TE

v_CT = v_CE + v_ET

speed = np.linalg.norm(v_CT)

angle = np.degrees(np.arctan2(v_CT[1], v_CT[0]))

print(f"v_CT = {v_CT} km/h")

print(f"|v_CT| = {speed:.1f} km/h")

print(f"direction = {angle:.0f} degrees north of east")

4.4.3.2. Example Problem: Flying a Plane in a Wind#

Exercise 4.13

The Problem

A pilot must fly a plane due north to reach their destination. The plane can fly at 300 km/h in still air. A wind is blowing out of the northeast at 90 km/h. (a) In what direction must the pilot head the plane to fly due north? (b) What is the speed of the plane relative to the ground?

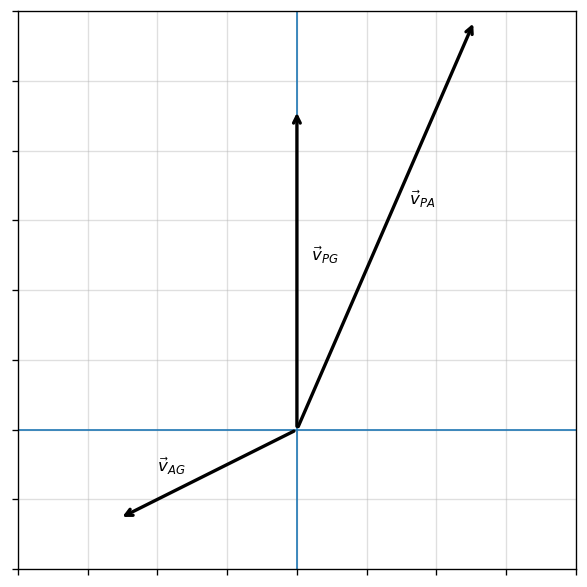

Fig. 4.12 Image Credit: OpenStax.#

The Model

We treat each velocity as a vector in the horizontal plane and use relative motion (vector addition). Let \(P\) = plane, \(A\) = air, and \(G\) = ground. The key relationship is

The pilot can control \(\vec{\rm v}_{PA}\) (speed \(300\ \text{km/h}\) and heading), while the wind sets \(\vec{\rm v}_{AG}\) (speed \(90\ \text{km/h}\) directed toward the southwest because it is “out of the northeast”). We choose axes with \(+\hat{i}\) east and \(+\hat{j}\) north.

The Math

The wind “out of the northeast” points \(45^\circ\) south of west, so

The plane’s airspeed has fixed magnitude \(|\vec{\rm v}_{PA}|=300\ \text{km/h}\), but the pilot aims it at an angle \(\theta\) east of north, so

To fly due north, the ground-track must have zero east-west component, so the \(x\)-component of \(\vec{\rm v}_{PG}\) must be zero:

Solving for \(\theta\),

So the pilot must point the plane about \(12^\circ\) east of north.

For the ground speed, we use the \(y\)-component of \(\vec{\rm v}_{PG}\):

The Conclusion

To keep the ground-track due north, the pilot must “crab” into the wind by aiming the nose about \(12^\circ\) east of north. The wind’s southward component reduces the northward progress, giving a ground speed of about \(230\ \text{km/h}\).

The Verification

We verify the heading by checking that the computed ground velocity has (approximately) zero \(x\)-component, and we make a minimal vector sketch.

# Verification: plane in a wind (vector addition)

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

vPA = 300.0 # km/h

vAG = 90.0 # km/h

deg = np.pi/180

# Wind "out of the NE" points toward SW: 45° south of west

vAG_vec = np.array([-vAG*np.cos(45*deg), -vAG*np.sin(45*deg)]) # [x,y]

# Solve for heading angle theta (east of north) so ground x-component is zero

theta = np.arcsin((vAG*np.cos(45*deg))/vPA) # radians

vPA_vec = np.array([vPA*np.sin(theta), vPA*np.cos(theta)]) # [x,y]

vPG_vec = vPA_vec + vAG_vec

speed_ground = np.linalg.norm(vPG_vec)

print(f"Heading: {theta/deg:.0f}° east of north")

print(f"Ground speed: {speed_ground:.0f} km/h")

print(f"Ground x-component (should be ~0): {vPG_vec[0]:.3f} km/h")

# Minimal sketch using annotate arrows

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(5,5), dpi=120)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ax.grid(True,alpha=0.4)

ax.axhline(0, lw=1)

ax.axvline(0, lw=1)

def draw_vec(vec, label, text_offset=(0,0)):

ax.annotate("",xy=(vec[0], vec[1]),

xytext=(0, 0),arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle="->", lw=2)

)

ax.text(0.55*vec[0] + text_offset[0],

0.55*vec[1] + text_offset[1],label

)

draw_vec(vAG_vec, r"$\vec{v}_{AG}$", text_offset=(-15, 5))

draw_vec(vPA_vec, r"$\vec{v}_{PA}$", text_offset=(5, 0))

draw_vec(vPG_vec, r"$\vec{v}_{PG}$", text_offset=(5, -5))

ax.set_xticklabels([])

ax.set_yticklabels([])

# --- set reasonable plot limits so the renderer doesn't explode ---

ax.set_xlim(-100, 100)

ax.set_ylim(-100, 300)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

Heading: 12° east of north

Ground speed: 230 km/h

Ground x-component (should be ~0): 0.000 km/h

4.5. In-class Problems#

4.5.1. Part I#

Problem 1

The 18th hole at Pebble Beach Golf Course is a dogleg to the left of length \(496.0\ \text{m}\). The fairway off the tee is taken to be the \(x\) direction. A golfer hits his tee shot a distance of \(300.0\ \text{m}\), corresponding to a displacement \(\Delta \vec{r}_1 = 300.0\ \hat{i}\ \text{m},\) and hits his second shot \(189.0\ \text{m}\) with a displacement \(\Delta \vec{r}_2 = 172.0\ \hat{i} + 80.3\ \hat{j}\ \text{m}.\)$ What is the final displacement of the golf ball from where it started?

Problem 2

Clay Matthews, a linebacker for the Green Bay Packers, can reach a speed of \(10.0\ \text{m/s}\). At the start of a play, Matthews runs downfield at \(45^\circ\) with respect to the \(50\)-yard line and covers \(8.0\ \text{m}\) in \(1.0\ \text{s}\). He then runs straight down the field at \(90^\circ\) with respect to the \(50\)-yard line for \(12.0\ \text{m}\), with an elapsed time of \(1.2\ \text{s}\).

(a) What is Matthews’ final displacement from the start of the play?

(b) What is his average velocity?

Problem 3

The position of a particle is given by \(\vec{r}(t) = \left(3.0t^2\ \hat{i} + 5.0\ \hat{j} - 6.0t\ \hat{k}\right)\ \text{m}\).

(a) Determine the velocity and acceleration as functions of time.

(b) What are the velocity and acceleration at \(t = 0\)?

4.5.2. Part II#

Problem 4

A projectile is launched at an angle of \(30^\circ\) and lands \(20.0\ \text{s}\) later at the same height as it was launched.

(a) What is the initial speed of the projectile?

(b) What is the maximum altitude?

(c) What is the range?

(d) Calculate the displacement from the point of launch to the position on its trajectory at \(15.0\ \text{s}\).

Problem 5

An astronaut on Mars kicks a soccer ball at an angle of \(45^\circ\) with an initial velocity of \(15.0\ \text{m/s}\). If the acceleration due to gravity on Mars is \(3.7\ \text{m/s}^2\),

(a) what is the range of the soccer kick on a flat surface?

(b) What would be the range of the same kick on the Moon, where gravity is one-sixth that of Earth?

Problem 6

A fairground ride spins its occupants inside a flying-saucer-shaped container. If the horizontal circular path the riders follow has a radius of \(8.00\ \text{m}\), at how many revolutions per minute are the riders subjected to a centripetal acceleration equal to that of gravity?

Problem 7

A seagull can fly at a velocity of \(9.00\ \text{m/s}\) in still air.

(a) If it takes the bird \(20.0\ \text{min}\) to travel \(6.00\ \text{km}\) straight into an oncoming wind, what is the velocity of the wind?

(b) If the bird turns around and flies with the wind, how long will it take the bird to return \(6.00\ \text{km}\)?