10. Celestial Sphere#

The celestial sphere is an imaginary sphere of gigantic radius, concentric with the Earth, onto which all celestial objects appear to be projected. It’s a fundamental concept in astronomy for understanding the positions and motions of objects in the sky.

10.1. The Ancient Greek Perspective#

Ancient Greek astronomers, like Aristotle and Ptolemy, didn’t know the Earth revolved around the Sun. From their Earth-centered (geocentric) perspective, it appeared as though the stars were fixed on a giant sphere that rotated around the Earth once a day.

Here’s how they likely constructed this idea:

Observation of Daily Motion: They observed that the Sun, Moon, planets, and stars rose in the eastern part of the sky and set in the western part. This suggested a daily rotation of something encompassing the Earth.

Fixed Patterns of Stars: While individual stars moved across the sky, their positions relative to each other (the constellations) remained constant. This implied they were attached to a single, rigid structure.

Apparent Dome of the Sky: The sky looks like a dome overhead. Extending this dome to be a full sphere surrounding the Earth was a natural geometric and conceptual leap.

Celestial Poles and Equator: They noticed that some stars in the north appeared to circle around a fixed point (the North Celestial Pole, near Polaris), while others rose and set. This led to the concept of celestial poles as the pivot points of this sphere and a celestial equator as the projection of Earth’s equator onto this sphere.

This model, while not physically accurate in terms of the universe’s structure, was incredibly useful for predicting the positions of celestial objects and for navigation. It remains a powerful tool for observational astronomy today.

10.2. Key Astronomical Terms#

Here are some fundamental terms associated with the celestial sphere:

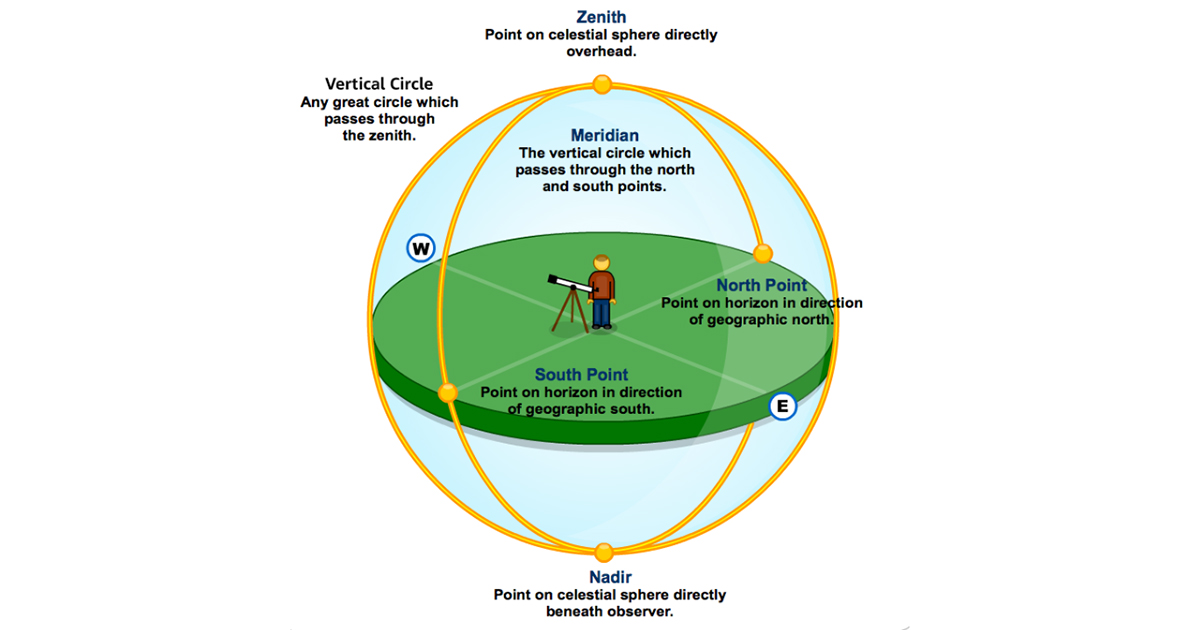

Zenith: The point on the celestial sphere directly above an observer.

Diagram:

Nadir: The point on the celestial sphere directly below an observer (opposite the zenith).

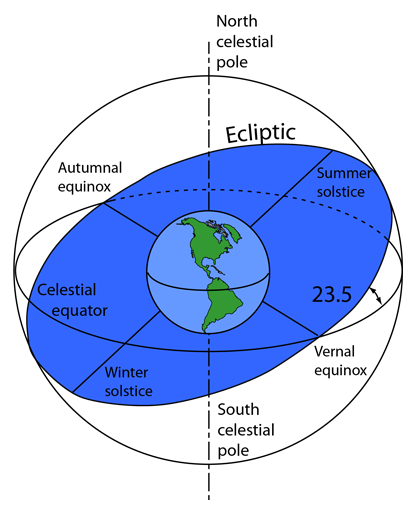

Celestial Poles (North and South): The points on the celestial sphere directly above the Earth’s North and South geographic poles. These are the points around which the celestial sphere appears to rotate.

Diagram:

Celestial Equator: The great circle on the celestial sphere in the same plane as the Earth’s equator. It divides the celestial sphere into northern and southern hemispheres.

Diagram: (See Celestial Poles diagram above, it’s usually shown together)

Horizon: The great circle on the celestial sphere that separates the visible sky from the invisible sky (below the observer). It’s where the sky appears to meet the Earth.

Diagram: (See Zenith diagram above)

Ecliptic: The apparent annual path of the Sun on the celestial sphere as viewed from Earth. It’s tilted at an angle of about \(23.5^{\circ}\) relative to the celestial equator because of the tilt of Earth’s axis. The planets and Moon also appear to move roughly along the ecliptic.

Diagram:

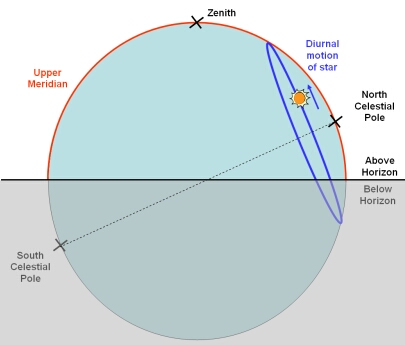

Meridian (Local Meridian): A great circle on the celestial sphere passing through the celestial poles and the observer’s zenith. An object is at its highest point in the sky when it crosses the meridian.

Diagram:

10.3. Finding Your Way: Altitude and Azimuth (Local Coordinates)#

To tell someone where to look for a star in their local sky right now, you use the altitude-azimuth system. This system is specific to the observer’s location and time.

Altitude (Alt): This is the angular height of an object above the observer’s horizon. It’s measured in degrees, from \(0^{\circ}\) at the horizon to \(90^{\circ}\) at the zenith. Objects below the horizon have negative altitudes.

Azimuth (Az): This is the angular distance measured clockwise around the observer’s horizon from a reference direction, usually North, to the point on the horizon directly below the object. It’s measured in degrees from \(0^{\circ}\) to \(360^{\circ}\).

North = \(0^{\circ}\)

East = \(90^{\circ}\)

South = \(180^{\circ}\)

West = \(270^{\circ}\)

How it works: Imagine pointing your finger towards the North on the horizon. Then, swing your arm to the right (clockwise) along the horizon by the azimuth angle. Finally, lift your arm upwards by the altitude angle. That’s where the object is!

Diagram:

Important Note: Because the Earth rotates, the altitude and azimuth of a star are constantly changing.

10.4. Universal Coordinates: Right Ascension, Declination, and Epoch#

To give a star a “fixed” address on the celestial sphere, much like longitude and latitude on Earth, astronomers use the equatorial coordinate system. These coordinates remain (mostly) constant for a star, regardless of the observer’s location or the time of day.

Declination (Dec, \(\delta\)): This is the angular distance of an object north or south of the celestial equator. It’s analogous to latitude on Earth.

Measured in degrees, minutes (‘), and seconds (“).

Positive values are north of the celestial equator (e.g., \(+30^{\circ}\)).

Negative values are south of the celestial equator (e.g., \(-15^{\circ}\)).

The celestial equator is \(0^{\circ}\) declination.

The North Celestial Pole is \(+90^{\circ}\) declination.

The South Celestial Pole is \(-90^{\circ}\) declination.

Right Ascension (RA, \(\alpha\)): This is the angular distance of an object measured eastward along the celestial equator from the vernal equinox to the hour circle passing through the object. It’s analogous to longitude on Earth.

The vernal equinox (also called the First Point of Aries) is the point on the celestial sphere where the Sun crosses the celestial equator moving from south to north, occurring around March 20th or 21st each year. This point is the \(0\) reference for Right Ascension.

RA is usually measured in hours (h), minutes (m), and seconds (s), from \(0\text{h}\) to \(24\text{h}\). This is because the Earth (and thus the celestial sphere) appears to rotate \(360^{\circ}\) in 24 hours, so 1 hour of RA = \(15^{\circ}\) of arc (\(360^{\circ} / 24\text{h} = 15^{\circ}/\text{h}\)).

An object with an RA of \(0\text{h}\) is at the vernal equinox. An object with an RA of \(6\text{h}\) is \(90^{\circ}\) east of the vernal equinox along the celestial equator.

Diagram for RA and Dec:

Epoch: Because of the Earth’s axial precession (a slow wobble in its rotational axis), the celestial poles and celestial equator shift very slowly over time. This means the vernal equinox also shifts, causing the Right Ascension and Declination of stars to change gradually.

Therefore, celestial coordinates are always specified for a particular epoch, which is a standard reference point in time.

The current standard epoch is J2000.0, which refers to January 1, 2000, at 12:00 Terrestrial Time. When you look up star coordinates in a catalog, they are usually given for J2000.0. For very precise observations over long periods, astronomers will calculate the coordinates for the current date, known as the “epoch of date.”

10.5. Best Right Ascension for Monthly Astronomical Observations#

For planning nighttime astronomical observations, you want to observe objects that are high in the sky, ideally near your local meridian, during the darkest part of the night (around midnight). The Sun is “opposite” this region of the sky.

The Sun’s Right Ascension changes throughout the year as it moves along the ecliptic. The objects best placed for viewing around midnight will have a Right Ascension roughly \(12\) hours different from the Sun’s current RA.

Here’s a general guide (these are approximate RAs that will be near the meridian around local midnight):

Month |

Best RA for Midnight Viewing (approx.) |

Sun’s Approximate RA |

|---|---|---|

January |

6h - 8h RA |

~18h - 20h |

February |

8h - 10h RA |

~20h - 22h |

March |

10h - 12h RA |

~22h - 0h |

April |

12h - 14h RA |

~0h - 2h |

May |

14h - 16h RA |

~2h - 4h |

June |

16h - 18h RA |

~4h - 6h |

July |

18h - 20h RA |

~6h - 8h |

August |

20h - 22h RA |

~8h - 10h |

September |

22h - 0h RA |

~10h - 12h |

October |

0h - 2h RA |

~12h - 14h |

November |

2h - 4h RA |

~14h - 16h |

December |

4h - 6h RA |

~16h - 18h |

How to use this:

Find the current month.

The listed RA range is what will be culminating (highest in the sky) around midnight.

Objects with RAs about 2-3 hours on either side of this range will also be well-placed for viewing earlier or later in the evening.

For example, in May, objects with RAs around \(14\text{h}\) to \(16\text{h}\) (like the Virgo Cluster or constellations such as Boötes and Libra) will be high in the sky around midnight. Objects with RAs of \(12\text{h}\) would be good to observe earlier in the evening, while objects with RAs of \(18\text{h}\) would be better later in the night/early morning.

Happy stargazing!