12. Dwarf Planets and Small Solar System Bodies#

12.1. Eccentric Orbits#

Most of the smaller Solar System bodies do not have near-circular orbits, especially those that are far from the Sun. They take many years to complete their orbits. Therefore astronomers take a different approach to determining their semimajor axis and eccentricity. As these bodies approach the Sun, they brightness increases until they reach perihelion (i.e. their closet approach to the Sun).

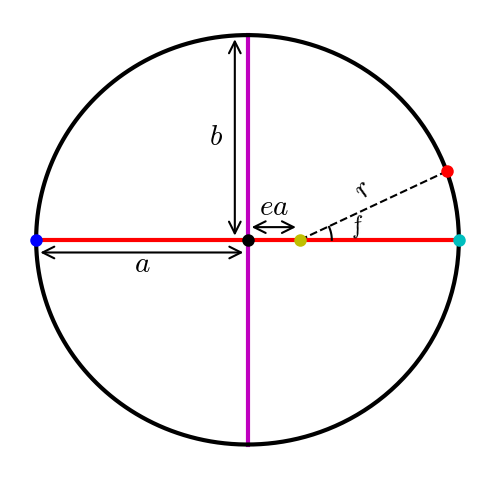

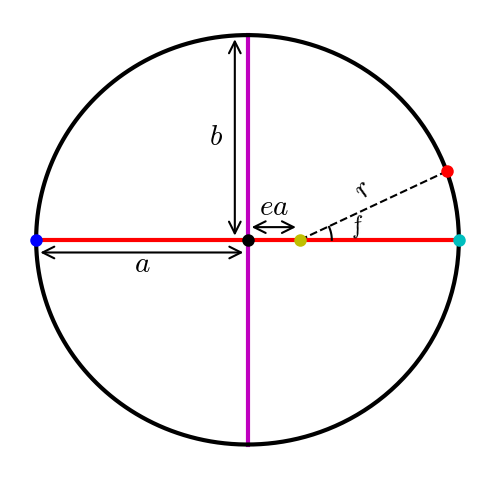

The figure below shows an orbit similar to Pluto’s, which demonstrates that Pluto’s orbit is mildly eccentric \((e=0.2488)\). To observe Pluto at its brightest, it must be near opposition (see the discussion in Chapter 3) relative to the Earth.

Fig. 12.1 Elliptical orbit similar to Pluto \((e=0.2488)\) with the Sun (yellow dot) at one focus, and the planet is past perihelion (cyan dot). The major axis (red line) connects the aphelion (blue dot) to the perihelion, where the semimajor axis \(a\) connects to the center (black dot) of the ellipse. The minor axis (magenta line) is perpendicular to the major axis, where the semiminor axis \(b\) is its respective half-length.#

Show code cell content

#Code to create Fig 2.1

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from scipy.integrate import odeint

from matplotlib import rcParams

from myst_nb import glue

rcParams.update({'font.size': 14})

rcParams.update({'mathtext.fontset': 'cm'})

def grav(x,t):

#derivative function for the two body problem in astrocentric coordinates

#state function x = {x,y,z,vx,vy,vz}

xp = np.zeros(6)

xp[:3] = x[3:] #{vx,vy,vz}

r = np.sqrt(np.sum(np.square(x[:3]))) #calculate the separation vector r

xp[3:] = -G*M_star*x[:3]/r**3

return xp

def Orb2Cart(a,e,omg,f):

#Calculate the Cartesian state given orbital elements (a,e,omega,f)

temp = np.zeros(6)

r = a*(1-e**2)/(1+e*np.cos(f))

n = np.sqrt(G*M_star/a**3) #mean motion n

rdot = n*a*e*np.sin(f)/np.sqrt(1.-e**2)

rfdot = n*a*(1+e*np.cos(f))/np.sqrt(1.-e**2)

omg_f = omg + f

temp[:3] = [r*np.cos(omg_f), r*np.sin(omg_f), 0.]

temp[3:] = [rdot*np.cos(omg_f) - rfdot*np.sin(omg_f),rdot*np.sin(omg_f) + rfdot*np.cos(omg_f),0]

return temp

G = 4*np.pi**2 #Constant for Universal Gravitation (units: AU, yr, M_sun)

M_star = 1 #Solar mass

a,e,omg,f = 1,0.2488,0,0

x_o = Orb2Cart(a,e,omg,f)

r_p, r_a = a*(1-e), -a*(1+e)

b = a*np.sqrt(1-e**2)

t_rng = np.arange(0,1.,1./365.25)

sol = odeint(grav, x_o, t_rng)

fs = 'medium'

lw = 2

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(4,4),dpi=150)

ax = fig.add_subplot(111)

ea = a*e

ax.plot([r_a,-ea],[0,0],'r-',lw=lw)

ax.plot([-ea,r_p],[0,0],'r-',lw=lw)

ax.plot([-ea,-ea],[0,b],'m-',lw=lw)

ax.plot([-ea,-ea],[0,-b],'m-',lw=lw)

ax.text(-ea-0.15,0.45,'$b$',horizontalalignment='center')

ax.annotate('', xy=(-ea-0.06, 0), xytext=(-ea-0.06, b), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='<->', color='k'))

ax.text(-ea+(r_a+ea)/2,-0.15,'$a$',horizontalalignment='center')

ax.annotate('', xy=(r_a, -0.06), xytext=(-ea, -0.06), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='<->', color='k'))

ax.text(-ea/2,0.12,'$ea$',horizontalalignment='center')

ax.annotate('', xy=(-ea, 0.06), xytext=(0, 0.06), arrowprops=dict(arrowstyle='<->', color='k'))

ax.plot(-ea,0,'k.',ms=10)

ax.plot(sol[:,0],sol[:,1],'k-',lw=lw)

ax.plot(r_p,0,'c.',ms=10)

ax.plot(r_a,0,'b.',ms=10)

ax.plot([0,sol[15,0]],[0,sol[15,1]],'k--',lw=1)

ax.plot(sol[15,0],sol[15,1],'r.',ms=10)

ax.plot(0,0,'y.',ms=10)

ax.text(0.3,0.20,'$r$',horizontalalignment='center',rotation=50)

ax.text(0.27,0.03,'$f$',horizontalalignment='center',rotation=10,fontsize='small')

arc_r = 0.15

ang_rng = np.radians(np.arange(0,25,1))

arc_x, arc_y = arc_r*np.cos(ang_rng), arc_r*np.sin(ang_rng)

ax.plot(arc_x,arc_y,'k-',lw=1)

#ax.set_xticks(np.arange(-1.5,1.5,0.5))

#ax.set_yticks(np.arange(-1,1.1,0.5))

ax.set_aspect('equal')

ax.axis('off')

glue("orbit_fig", fig, display=False);

Kepler’s laws showed us that an eccentric orbit has two special points where the speed of the orbiting object is fastest (perihelion) and slowest (aphelion). Those two points coincide to when the object is closest (\(q\); perihelion) and farthest (\(Q\); aphelion) from the Sun. We can calculate these distances using the semimajor axis and eccentricity by:

Notice that the only difference between these values is the sign in front of the eccentricity \(e\).

What are the aphelion and perihelion distances for the Apollo asteroid 2005 YU55, which has a semimajor axis of \(1.14\ {\rm AU}\) and an eccentricity of \(0.43\)?

Solving this problem is straightforward (i.e., no unit coversions!), where we can just substitute values. This is done by,

The perihelion lies interior to Earth’s orbit, while the aphelion lies just beyond Mars’ semimajor axis. This indicates that 2005 YU55 crosses both the orbits of Earth and Mars. In November 2011, it passed \(324,900\ {\rm km}\) from Earth.

12.2. Impact Energy#

The energy of a moving object depends on the object’s mass \(m\) and how fast its going (or its velocity) \(v\). In physics, we represent this energy as

where \(E_{\rm K}\) is the kinetic energy in joules (J), \(m\) is the mass (in kg), and the velocity \(v\) (in \(\rm m/s\)). The kinetic energy is the maximum amount of energy that an asteroid of comet can deliver upon impact.

Suppose an asteroid (or comet nucleus) is \(10\ {\rm km}\) in diameter and has a mass of \(5\times 10^{14}\) strikes Earth at a speed of \(20\ {\rm km/s}\). How much energy could it deliver on impact?

This calculation requires us to first convert everything into the applicable units. Specifically, we need the speed to be in \(\rm m/s\) so that we can substitute into the above equation and get the right units at the end. Therefore, we convert the speed by

Now we can substitute to find \(E_{\rm K}\) as,

This seems like a lot of energy, where \(10^{23}\ {\rm J}\) is a big number. Let’s put this into context.

A 1-megaton hydrogen bomb (\(67\times\) as energetic as the Hiroshima atomic bomb) releases about \(10^{15}\ {\rm J}\) of energy. The impact of this object would deliver as much energy as

The World consumption of electricity in 2022 (Wikipedia:World_energy_consumption) was approximately \(24,200\ {\rm TWh}\), where \(1\ {\rm Wh} = 3600\ {\rm J}\). We want to find the total consumption in \(J\) so that we can compare apples-to-apples. This is given by,

The impact of a \(10\ {\rm km}\) asteroid at \(20\ {\rm km/s}\) delivers enough energy to power the world for \({\sim}1140\) years!